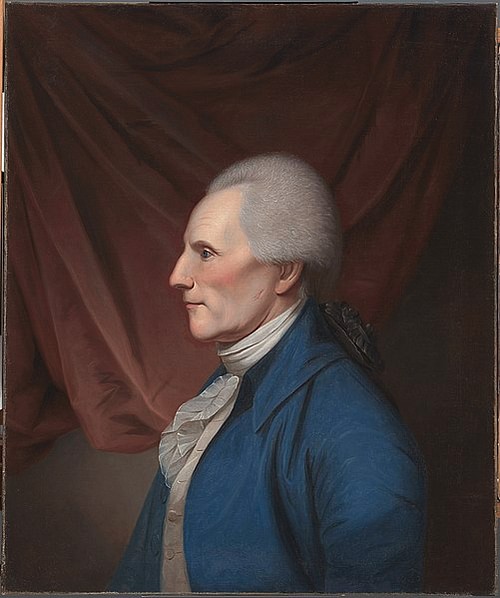

Henry Lee III (1756-1818), more commonly known by his nickname 'Light-Horse Harry' Lee, was a cavalry officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and a politician who served as the ninth Governor of Virginia (1791-1794). A member of the prominent Lee family of Virginia, he is best remembered today as the father of Robert E. Lee.

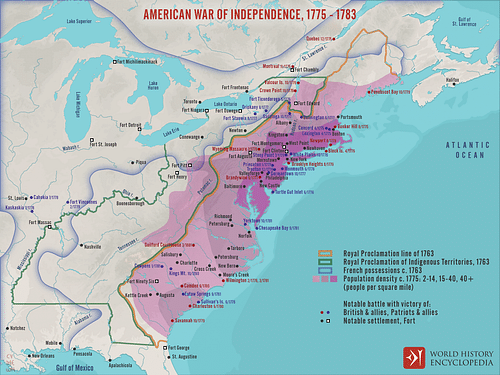

Having enlisted as a cavalry officer shortly after the outbreak of the war, Lee proved to be a talented soldier, leading effective scouting missions, guerilla-style ambushes, and a daring nighttime raid on the British fort at Paulus Hook, New Jersey, in August 1779. Promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1780 at the age of only 24, he led the elite Lee's Legion into several significant engagements in the southern theater of war, such as Pyle's Massacre, the Battle of Guilford Court House, and the Battle of Eutaw Springs. After the war, he entered politics, serving at both state and federal levels; an ardent member of the Federalist Party, he devoted his political career to the maintenance of a strong central government.

Although he came from one of Virginia's wealthiest families, Lee was horrible with his finances and was constantly in debt. In 1809, he was even thrown into debtor's prison for a year. After suffering multiple injuries at the hands of an angry mob in July 1812, Lee's health steadily declined until he died on 25 March 1818 at age 62. A prominent figure of the American Revolution, the accomplishments of 'Light-Horse Harry' Lee are often overshadowed in the annals of American history by those of his more famous son.

Early Life & Family

Henry Lee III was born on 29 January 1756 at Leesylvania Plantation, near the tobacco port of Dumfries in Prince William County, Virginia. He was the eldest of eight children born to Colonel Henry Lee II, a lawyer and politician who served in the House of Burgesses intermittently between 1758 and 1772. His mother, Lucy Grymes Lee, had briefly been courted by George Washington before opting to marry Henry Lee II instead, although she remained on good terms with the future general. Several of 'Light-Horse' Harry's younger brothers would also become prominent figures, such as future attorney general Charles Lee (1758-1815; not to be confused with the Continental Army general of the same name) and Richard Bland Lee (1761-1827), who would one day serve in the House of Representatives.

The Lee family was one of the wealthiest and most influential families in the colony of Virginia. It had been founded in 1639 by Richard Lee 'the Immigrant', who had come to the Jamestown Colony of Virginia from England with ambitions of becoming a tobacco planter. By his death in 1664, he had more than succeeded; the first Richard Lee left behind a lucrative tobacco enterprise and a vast fortune to be inherited by his eight children. By the 1750s, the sprawling Lee family was geographically divided into two main branches: Henry Lee II and his children made up the 'Leesylvania' branch, located on that plantation, while his first cousin, Richard Henry Lee, headed the other 'Stratford' branch of the family based around the estate of Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County. Both branches actively grew tobacco on their plantations, which was cultivated by scores of enslaved people.

Not much is known about the childhood of Henry Lee III. He was likely educated by private tutors at Leesylvania, although he certainly showed a propensity for classical literature and horseback riding. In 1770, he enrolled at the College of New Jersey (modern Princeton University) and graduated three years later at the age of 17. His initial plan was to go to England to continue his education, where he hoped to study law, but rising tensions between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies led him to change his mind. For over a decade, the colonists had been resisting Parliamentary tax policies, arguing that 'taxation without representation' violated their natural and constitutional rights. In Virginia, the Lee family was at the forefront of the struggle; Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, of the Stratford branch, were both prominent members of the Continental Congress and eventual signers of the Declaration of Independence, while Henry Lee II was a member of the revolutionary Virginia Conventions.

Light-Horse Harry

Inspired by his relatives, Henry Lee III decided to set aside his legal ambitions to aid the Patriot cause. On 18 June 1776, a year after the war had begun and only several weeks before independence, Henry Lee III was commissioned as a captain in a cavalry regiment of the Virginia militia. The following spring, his company was attached to the Continental Army, just in time to participate in the Philadelphia Campaign (July 1777 to June 1778). During the campaign, Lee was often sent out ahead of the main army on reconnaissance missions; his speed and efficiency earned him the nickname 'Light-Horse Harry'. Lee also earned a reputation as a cunning guerilla fighter, leading ambushes against British patrols and raiding enemy supply lines. On 20 January 1778, while the Continental Army was wintering at Valley Forge, Henry Lee III beat back a British patrol led by Banastre Tarleton at Spread Eagle Tavern, 5 miles (8 km) south of the American encampment. For this action, he was promoted to the rank of major and given command over a mixed unit of cavalry and infantry. He was still only 22 years old.

After the Continental Army left Valley Forge, it marched back into New Jersey to keep an eye on the main British army headquartered in Manhattan. The British occupied several key outposts in New York State and New Jersey that General Washington hoped to capture. One of these outposts, at Stony Point, New York, was captured by American troops under Brigadier General 'Mad' Anthony Wayne in a daring nighttime attack on 16 July 1779. Hoping to emulate Wayne's success, Major Lee began planning a raid against the isolated British post at Paulus Hook, New Jersey (now part of downtown Jersey City). After scouting the approaches to Paulus Hook and gathering information about the garrison from a British deserter, Lee assembled a force of around 400 infantrymen and, on the evening of 18 August 1779, moved south from New Bridge (modern River Edge, New Jersey) to begin a 14-mile (22 km) march through the woods.

Lee's attack soon faced difficulties. As the sun began to set, Lee realized that his principal guide had gotten them lost; whether this was intentional or accidental is unknown. The column corrected course but was now three hours behind schedule. To make matters worse, around 100 of Lee's men became separated from the column. Despite these setbacks, Lee decided to press on, and his column arrived outside Paulus Hook close to 3 a.m. on 19 August. After briefly pausing to reconnoiter a path through the salt marshes, Lee divided his men into two columns for the assault. With fixed bayonets, they rushed into the fort, surprising the sentries and overwhelming the garrison.

In less than 30 minutes, 'Light-Horse Harry' Lee had compelled the British commander to surrender; Lee lost 2 killed and 3 wounded, while the British garrison suffered 30 casualties. Lee had initially planned to burn the fort's barracks but decided against it when he discovered that they were occupied by sick men, women, and children. They took 159 prisoners, withdrawing from the fort before the British army had a chance to send reinforcements. For his victory at Paulus Hook, Henry Lee III became the only Continental officer below the rank of general to be awarded a gold medal by Congress. Despite his success, he was court-martialed on eight charges related to his conduct at Paulus Hook, although he was ultimately acquitted on all counts.

Lee's Legion

On 6 November 1780, Lee was promoted to lieutenant colonel and was given command of a legionary corps that consisted of three cavalry and three infantry units. The 300 officers and men of this corps, later known as Lee's Legion, were handpicked from other units, creating an elite unit that was soon recognized as "the most thoroughly disciplined and best equipped scouts and raiders in the Revolution" (quoted in Boatner, 615). They were outfitted in short, green jackets and white doeskin pants, similar to the uniforms worn by the infamous British Legion of Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton; Lee's Legion was, in many ways, the American answer to Tarleton's Legion. In command of his own unit, Lee implemented harsh discipline. In one instance, he beheaded a deserter and had the man's head displayed in his camp as a warning to the other soldiers. While executing deserters was considered acceptable at the time, Lee's method of beheading was considered barbaric by other Continental officers, and he was ordered not to do it again by Washington.

By late 1780, the war in the north had reached a stalemate, and Lt. Colonel Lee was sent to join Major General Nathanael Greene, who was conducting military operations in the South. Lee arrived in South Carolina in mid-January 1781, joining with Patriot partisans under the 'Swamp Fox', Brigadier General Francis Marion, in an assault on a British outpost at Georgetown. The following month, Lee's Legion covered Greene's main army as it retreated through North Carolina toward the Dan River, with a British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis hot on its heels. On 25 February, Henry Lee III attacked a company of Loyalist militia under Dr. John Pyle in Alamance County, North Carolina. Pyle's Loyalists mistook the green-coated riders of Lee's Legion for Tarleton's British dragoons and did not realize they were under attack until Lee's men opened fire. In the lopsided battle that followed, nearly 300 of the Loyalists were killed or wounded before the survivors scattered into the woods; Lee, on the other hand, lost no men in the fight. The skirmish, known as Pyle's Massacre, was a major blow to British morale.

On 15 March 1781, Greene and Cornwallis finally had their showdown at the Battle of Guilford Court House near modern-day Greensboro, North Carolina. In the morning hours before the battle, Lee's Legion was sent ahead to scout the British position. While doing so, they ran into Tarleton's Legion, which had been sent out for the same purpose. In the brief cavalry battle that followed, Lee's men were chased off; Tarleton took several prisoners but had lost two fingers in the engagement. Lee's Legion returned to the American defensive lines and participated in the ensuing battle; although Greene's army was ultimately defeated, it was able to withdraw from the battlefield intact, having inflicted a significant number of casualties on Cornwallis' British army.

After Guilford Court House, Cornwallis marched north into Virginia, where he was soon holed up in Yorktown. Greene's army moved back into South Carolina to begin liberating that state from the British forces that Cornwallis had left behind. Lee's Legion remained with Greene, participating in the Siege of Ninety-Six (22 May to 18 June 1781) and the Battle of Eutaw Springs (8 September). In October, Lee was sent to carry dispatches to Washington, who was then conducting the Siege of Yorktown; Lee was present when Cornwallis surrendered on 19 October 1781, bringing the active phase of the Revolutionary War to a close.

Marriages & Children

After Yorktown, Lee found that he was growing restless; once the ceasefire had gone into effect, Lee's legion had little to do. In February 1782, he took a leave of absence from the army and never returned. He was honorably discharged when the war officially ended the following year. In April 1782, he married his second cousin, Matilda Ludwell Lee, the 18-year-old heiress to Stratford Hall; the marriage united the Stratford and Leeslyvania branches of the family. The couple had three children – Philip Ludwell Lee (1784-1794), Lucy Grymes Lee (1786-1860), and Henry Lee IV (1787-1837), the latter of whom would go on to serve as a speechwriter for Andrew Jackson.

Shortly after his marriage, 'Light-Horse Harry' Lee began buying large tracts of land on credit, borrowing tens of thousands of dollars and quickly falling into debt. Around the same time, he experienced the tragic losses of both his father, who died in 1787, and his wife Matilda, who died in 1790. On her deathbed, Matilda put Stratford Hall in trust to her children; but, due to her husband's poor financial decisions, she left that trust to a cousin rather than with Lee himself. In 1793, Lee remarried to 20-year-old Anne Hill Carter and moved onto her family estate at Shirley Plantation. This second marriage would produce five more children who lived to adulthood, including lawyer and poet Charles Carter Lee (1798-1871), Anne Kinloch Lee (1800-1864), Confederate naval officer Sydney Smith Lee (1802-1869), and Mildred Lee (1811-1856). But it was the fourth surviving child of Henry and Anne, Robert Edward Lee (1807-1870) who would go down in history as the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Politics

Henry Lee III entered politics in 1786 when he was elected as a delegate to the Confederation Congress. In this capacity, Lee realized that the central government of the United States was much too weak under the Articles of Confederation and became a strong supporter of replacing the Articles with the US Constitution, which would allow for a stronger federal government. In 1788, Lee served in the convention that ratified the Constitution for the Commonwealth of Virginia. In 1791, he was elected as the ninth Governor of Virginia, serving three consecutive one-year terms.

In 1794, the Whiskey Rebellion, an armed tax protest in western Pennsylvania, was reaching its climax. President Washington enlisted Lee's help in suppressing the rebellion; Lee was promoted to major general and given command over 12,000 federal militiamen. Although the rebellion was soon quelled, the Virginia General Assembly decided that Lee could not hold a position answerable to the federal government (i.e. major general) while simultaneously serving as governor of Virginia. The Assembly therefore declared the office of governor vacant before the official end of Lee's term, much to his embarrassment. In 1798, during the so-called Quasi-War with France (1798-1800), Lee was once again commissioned as a major general in the newly established United States Army. The following year, he was elected to the House of Representatives as a member of the Federalist Party, serving until 1801.

Lee delivered the eulogy at the funeral of George Washington on 26 December 1799. Speaking before a crowd of 4,000 people, Lee famously proclaimed that Washington had been:

First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen…when our monuments shall be done away, when nations now existing shall be no more; when even our young and far-spreading empire shall have perished, still will our Washington's glory unfaded shine.

(mountvernon.org)

Later Life

In 1801, Lee retired from public life and returned to Stratford Hall. He spent the next several years trying to manage the estate, but to no avail; thanks to 'Light-Horse' Harry's mismanagement of the estate, the Lees would be forced to sell Stratford Hall in the 1820s, exactly what Matilda Lee had feared on her deathbed. In the meantime, Henry Lee was still unable to pay off his debts. In 1809, he declared bankruptcy and spent a year in a debtor's prison in Montross, Virginia. While in prison, he began work on an autobiography entitled Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States; the memoir, however, never sold well after its publication in 1812. After his release in 1810, Lee moved with his family to Alexandria, Virginia.

Like many others in the Federalist Party, Lee opposed the War of 1812, viewing it as an unnecessary conflict engineered by President James Madison to further the interests of the Democratic-Republican Party. In July 1812, Lee traveled to Baltimore, Maryland, in support of his friend Alexander C. Hanson, editor of the Federal Republican newspaper who had recently come under fire from Democratic-Republican critics for his opposition to the war. On 26 July 1812, an outraged, drunken mob of Democratic-Republican supporters attacked the newspaper's offices where Lee, Hanson, and several other Federalists had taken shelter. Lee was badly beaten by the mob; his cheek was sliced open by a pocketknife, and his attackers tried to gouge out his eyes. Although Lee survived the attack, his health never fully recovered. The attack also left him mentally distressed; for the rest of his life, he exhibited symptoms that are now associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Lee returned home to Alexandria but was both unable to recover and still hounded by his creditors. In 1813, he decided to go to the West Indies for his health and spent the next few years traveling throughout the Caribbean, all the while writing letters to his wife and children. As his health only continued to deteriorate, Lee eventually realized that he was dying, and he returned to the United States in early 1818 so he could see his family one last time. He would never make it, as he died shortly after landing on Cumberland Island, Georgia, on 25 March 1818; in his final days, he was nursed by Nathanael Greene's daughter, Louisa. 'Light-Horse Harry' Lee was buried on the island in full military honors. In 1913, his remains were relocated to the Lee family crypt at Washington & Lee University, where he was interred alongside his more famous son, Robert.