Sir Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688) was a Welsh privateer who operated in the Caribbean against the Spanish Empire and then became Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. Morgan was a charismatic and able military leader who masterminded devastating buccaneer attacks on settlements like Portobelo, Maracaibo, and Panama on the Spanish Main.

Morgan was a thorn in the side of the Spanish Empire across two decades, and he was utterly ruthless against the armies and civilians of Spain alike. As the deputy governor of Jamaica, he improved the island's fortifications and helped make Port Royal one of the busiest and richest ports in the New World. He ended his career as a respectable plantation owner but died from ill health, his constitution in no way helped by his bon vivant lifestyle.

Buccaneers & the Spanish Main

The buccaneers of the Caribbean were originally hunters, but by the 1660s, they had swelled in numbers to become a motley bunch of ex-soldiers, mariners, and escaped slaves. British, Dutch, and French colonial authorities were keen to use the buccaneers as an extra defence against the Spanish who dominated the region thanks to their control of the mainland – the Spanish Main – and their far greater number of warships. Not exactly a professional fighting force, the buccaneers were, nevertheless, skilled with their muskets and capable of both capturing Spanish ships at sea and launching amphibious assaults on Spanish fortifications and ports.

What the buccaneers and the colonial authorities needed most in their on-off war with Spain was men of talent and charisma to lead large assaults on Spanish treasure ships and settlements in the Americas. As the Spanish Crown still insisted that no other European traders were welcome in their empire, their colonial rivals – whatever their public stance – were highly supportive of anyone who attacked and weakened the Spanish by whatever means possible. One of the great buccaneer leaders, perhaps the greatest, was Captain Henry Morgan.

Early Life

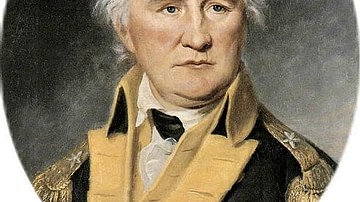

Henry Morgan was born around 1635 in Wales (perhaps either in Llanrumney or Penkarne as two of Morgan's plantations on Jamaica were named after these towns), but few details are known of his early years except that his formal education was brief. The historian P. Wood gives the following description of Morgan:

He was not a large man, but he was lean and strong, with a Welshman's swarthy complexion, a prominent nose, sensuous lips and dark, arrogant eyes. In personality, he was difficult to judge. His tongue carried both a lilt and a lash. (128)

Morgan came to Jamaica either with or shortly after the English force sent by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) in 1655 to take the island as a British possession. The island's main harbour, Port Royal, became the most notorious of the buccaneer havens and a perpetual thorn in the side of the Spanish Empire. Without an official naval presence, successive governors actively encouraged buccaneers of all nationalities to operate from Port Royal and attack the Spanish Empire. Official commissions were issued known as Letters of Marque (aka Letters of Reprisal) and so the buccaneers were, strictly speaking, privateers and not out-and-out pirates who attacked just anyone. In practice, however, the commissions were usually restricted for attacks on Spanish shipping and not ports. Many buccaneers ignored this distinction since booty taken from ships had to be shared with the authorities while that taken from ports was entirely their own. Another greyness to add to an already shady business was that there were intermittent official wars between England and Spain, and during these, any target whatsoever might be considered legitimate.

From 1658, Morgan operated as a privateer under the command of Sir Christopher Myngs (also spelt Mings, 1620-1666) and attacked Spanish colonial possessions in Cuba and Mexico with great success. Morgan learnt much for Myngs such as the value of swift surprise attacks on fortifications from an unexpected quarter. In 1662, Morgan must have impressed as he was made a militia officer and captain of a prize vessel. Morgan embarked on a 22-month voyage and conducted privateering attacks in Central America, hitting Villahermosa in 1664 and Tabasco and Gran Granada in 1665. These successes would lead to even bigger campaigns for the Welsh buccaneer as he became the commander of the Port Royal militia and the de facto leader or 'Admiral' of the Caribbean buccaneers.

The Attack on Portobelo

In 1668 Morgan was charged with leading a multinational force of buccaneers in an attack on the Spanish treasure port of Portobelo on the coast of what is today Panama. One of Spain's big three treasure ports, Portobelo was a depot for the huge quantities of silver gathered from mines in South America. Spain and England had agreed in 1667 not to attack each others' possessions, but the prize was simply too tempting to resist. In addition, the then governor of Jamaica, Thomas Modyford (1620-1679), had heard rumours that the Spanish were preparing for an attack on the island. A pre-emptive strike was a sensible strategy, although Morgan was supposed to limit himself to capturing treasure ships either in port or at sea. Modyford was particularly keen for Morgan to capture Spaniards and find out any useful information they possessed. Those might have been his official orders, but the Welsh buccaneer harboured far greater ambitions than that.

First, Morgan assembled his multinational force at Providence Island, aka Isla de Providencia off the coast of Central America, an island he had taken from the Spanish in 1665. He commanded some 700 men in 12 ships. Morgan began by avoiding well-fortified Havana and instead attacking Puerto Principe, a centre for the hide trade further down the coast of Cuba. However, the booty taken was disappointing, and Morgan's French buccaneers left the expedition at this point.

Morgan's force was bolstered by the arrival of another shipload of English buccaneers, and he turned his attentions to Portobelo, which was well protected by three separate fortresses bristling with 60 cannons in all. Morgan, though, knew, like other Spanish settlements that had yet to face the fury of the buccaneers, these defences were woefully undermanned and had only out-of-date cannons and limited ammunition, some of which had become so rusty from neglect that it was now unusable. In July 1668 Morgan attacked and captured Portobelo. He used 23 canoes to land 500 men a few miles from the town and then marched to surprise the Spanish who were expecting an attack from the sea. Prisoners, who included women, priests, and nuns, were used as human shields to carry ladders to the fortification walls for the buccaneers to gain entry.

After the victory, prisoners were tortured to reveal their valuables, a common practice in the brutal world of buccaneers. One lady, Doña Augustín de Rojas, was stripped of her clothes, made to stand in a barrel of gunpowder, and threatened with a lit fuse unless she revealed where her jewels had been hidden. The town was then ransomed back into Spanish hands; the local population even contributed 100,000 silver pesos to the pot. With the governor of Panama chipping in more cash after a relief force had been defeated, Morgan managed to acquire a total haul of loot plus ransom worth 250,000 pesos. It was an absolute fortune and the main reason why overstepping his Letters of Marque was forgiven and forgotten by the Jamaican authorities. In March 1669, the booty taken from Portobelo was declared a legal prize by the Admiralty Court. There was now nothing to hinder Morgan from attacking any target he wished.

The Attack on Maracaibo

After a refreshing spell of rest and debauchery back at Port Royal, Captain Morgan assembled a new buccaneer force in October 1668. He received the welcome addition of a naval frigate from Governor Modyford, the Oxford, which sported 26 or 34 cannons depending on one's source. Unfortunately, a party on board the Oxford in January 1669 to celebrate setting sail on the morrow ended in the drunken buccaneers firing off their pistols and setting fire to the ship’s gunpowder stores. The resulting explosion wrecked the ship and killed near 200 men; Morgan was one of only ten survivors. The dreadful loss meant the original target of the treasure port Cartagena was now no longer realistic. Another, less well-defended port would have to do.

Morgan sailed to attack the fort at Santiago in Cuba, where he again used prisoners as human shields. In April 1669, Morgan next attacked Maracaibo on what is today the coast of Venezuela. He first took the small fortress which guarded the channel that gave access to Lake Maracaibo. The bastion had been built by the Spanish after the French buccaneer François L'Olonais (c. 1630-1668) had attacked Maracaibo two years before. The fort did not stop Morgan's men, who found the place empty but with a fuse burning towards a massive depot of gunpowder. The fuse was put out just in time, and the marauders pushed on to Maracaibo otherwise unhindered. The town had by then been abandoned and was easily taken and looted.

Things could then have gone very badly indeed for the buccaneers when three Spanish warships trapped them in the Maracaibo lagoon. Morgan now made one of his inspired tactical decisions and decided to dress up a captured merchant ship and send it into the Spanish fleet, where it might be exploded. The ship was given gun ports with painted logs in them to look like cannons, and there were even a number of painted and dressed wooden figures on deck to make it look like the ship was carrying a normal crew. Down in the hold, barrels of gunpowder were placed with quick fuses and a large quantity of brimstone and tarred palm leaves. Waiting for night to fall, just 12 men sailed the floating bomb towards the Spanish, and when they reached the enemy vessels, they departed unseen in a small boat. The flagship of the Spanish fleet, the 48-gun Magdalen, was set ablaze by the exploding ship, and the buccaneers went on the attack, capturing one of the other Spanish vessels, the 24-gun Marquesa, while the third Spanish ship ran aground in the general confusion. There was still the channel fortress to negotiate, now back in Spanish hands. Morgan devised another ruse where he repeatedly sent boats full of men to the shore and had the boats return with the same men hidden out of sight. The Spanish were fooled into thinking the buccaneers were planning a land assault and so moved their cannons to cover that side of the fortress. Morgan's buccaneers then sailed off in the night to the open sea and safety carrying 250,000 silver pesos in loot.

The Attack on Panama

Morgan returned triumphant to Port Royal, took stock, and sent a call out for more buccaneers of all nationalities to join him at a point of assembly at Cape Tiburon, Hispaniola. In the meantime, Morgan recaptured Providence Island from the Spanish in 1670 despite England and Spain having just agreed a peace with the Treaty of Madrid (news of this peace would take a year to reach the Caribbean). The Spanish also continued small-scale attacks on British settlements and now authorised Spanish vessels to take British ones at sea as prizes if they could.

By the end of 1670, Morgan's buccaneers, now consisting of up to 2,000 men in 33 ships, were ready to roll on to their target: Panama. Morgan commanded the fleet in his 22-gun frigate Satisfaction, an apt name given the final outcome of the raid on a city that had never fallen from Spanish control. After taking with some difficulty the San Lorenzo fortress which guarded the Chagres River, the buccaneers headed towards Panama at the end of December, the last few miles approaching by land as they cut their way through the jungle with machetes. Panama was easily captured in January 1671 since it had no defensive fortifications whatsoever and two-thirds of the garrison had already deserted in fear of the buccaneers' terrible reputation. The Spanish militia did try to disrupt the buccaneer ranks by setting loose cattle to stampede the battlefield but to no avail. Morgan's attack on the Spaniards' weak right flank and the coordinated and disciplined volley fire of the buccaneers won the day.

Panama was burned to the ground, although this was likely intentional by the Spanish and unintentional by the buccaneers since the blaze damaged both goods and the prospect of gaining a handsome ransom from the Spanish authorities. The locals did later rebuild their port a little way down the coast, a site that eventually became Panama City. This area of the Spanish Main had long been in decline, and the buccaneers, missing the annual treasure ships, did not get much in return for their efforts since the Spanish had emptied the city of valuables and sent them by ship elsewhere. When what loot they found was shared out amongst the great number of participants, the booty was small indeed for the rank and file. Morgan was accused of cheating his men out of their booty, and many were left to nearly starve.

In response to Morgan's raids, the Spanish demanded action from the British government. Accordingly, Morgan was arrested and sent to London in April 1672, but many in positions of power, even if their public voice was different, privately considered Morgan a true patriot whose actions might force Spain to open up their empire to British traders. The ship that brought back Morgan to England was aptly named the Welcome. Morgan was never imprisoned – unlike Governor Modyford who spent two years in the Tower of London – and when the diplomatic dust settled in January 1674, Morgan was knighted by Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685) and sent back to the Caribbean where he took up his new post as Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica.

Lieutenant Governor of Port Royal

Port Royal at its height was awash with people, goods, and riches, so much so that one contemporary author described it as having more cash than London. By 1680, the haven's prosperity is evidenced by the presence of over 100 taverns. There were, too, so many gaming houses and brothels that a visiting clergyman described Port Royal as "the Sodom of the New World" (Breverton, 260) in reference to the biblical city infamous for its debauchery. Serving as deputy governor until 1682, Morgan may not have made much effort to clean up Port Royal but he did improve the defensive fortifications and defended the plantation owners against taxes proposed by the British government in London.

Morgan owned several large sugar plantations on Jamaica, a symbol of respectability he had first acquired back in 1665 following his marriage to his cousin Mary Elizabeth, the daughter of his uncle Sir Edward Morgan. Henry Morgan had no children, or, at least, no legitimate ones.

The former buccaneer turned against the men who had helped make his name and fortune and set about eradicating buccaneers and pirates from the western Caribbean. In any case, the colonial authorities now realised that encouraging lawless pirates was hardly conducive to establishing successful colonies, and the Spanish had become a much more formidable enemy following some serious investment in fortresses, weapons, and men. Many buccaneers continued piracy by attacking any easy merchant vessel they came across, and so the so-called Golden Age of Piracy began (1690-1730), but the now well-defended Spanish Empire was no longer the primary target of lawless cut-throats.

Death & Legacy

On 25 August 1688, Morgan died aged 53 of ill health after his body finally rebelled against his habit of heavy drinking and heavy eating. He was given a burial with full military honours. Unfortunately, Morgan did not long rest in peace since an earthquake struck Port Royal in June 1692, and part of the town slid under the sea forever, including Morgan's last resting place, now five fathoms deep.

Captain Morgan's legend began even in his own lifetime thanks to his deeds covered in the London press and such influential works as The Buccaneers of America by the Dutchman Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin, published in English in 1684. Exquemelin's work offers an invaluable insight into the period, although he does delight in reporting the more gruesome aspects of buccaneering. Exquemelin seems to have taken a hearty dislike to Morgan, in particular. It is perhaps significant that the author was one of the buccaneers disappointed by the booty taken at Panama. Morgan objected to his portrayal as a ruthless and unprincipled pirate and sued both of Exquemelin's publishers for libel, successfully reaching an out-of-court settlement and appropriate revisions of the original edition. Captain Morgan's exploits as a charismatic and highly successful buccaneer have firmly cemented his place in the history of colonial America, a position which today is further strengthened by having a globally popular spiced rum named after him.