Henry V of England ruled as king from 1413 to 1422. Succeeding his father Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413), Prince Henry established himself as a fine military leader in battles against English and Welsh rebels in the first decade of the 1400s. As king, Henry masterminded a famous victory against the French at the Battle of Agincourt in October 1415, went on to capture Normandy and Paris, and was even nominated as heir to the French throne. Henry's spectacular reign then came to a sudden and unexpected end when he died, probably of dysentery in August 1422 while on campaign in France; he was succeeded by his son Henry VI of England (r. 1422-1461 & 1470-1471).

Family & Early Life

Henry was born on 16 September 1387 at Monmouth Castle, the son of Henry IV of England, the first of the kings of the House of Lancaster, and Mary of Bohun (b. c. 1369). The ousting of Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399) by Henry IV in 1399 (when he was known as Henry Bolingbroke) and the murder of the ex-king in Pontefract Castle in 1400 would come back to haunt the House of Lancaster but for now, Prince Henry had no doubts about his role in the world: to one day rule England and then to conquer France.

Henry, often called Henry of Monmouth prior to his accession, was a very pious individual and developed a taste for an ascetic lifestyle as king, but in his youth, he was known for his partying. The young Henry spent time at Richard's court - even when his father was exiled - and he also learnt about arms and warfare from his guardian, the celebrated medieval knight Sir Henry 'Hotspur' Percy (1364-1403). Indeed, the prince learnt rather too well from the old master, and when the 'Hotspur' turned against the king, he was killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury in July 1403 in which the 16-year-old Henry fought with aplomb, although he received a facial wound for his trouble.

Prince Henry led the king's army which finally quashed the Welsh rebellion led by Owain Glyn Dwr (b. c. 1359). Perhaps Henry had been especially miffed that Owain had declared himself the Prince of Wales, which as the English king's eldest son, was rightfully Henry's title. In 1409 the rebel stronghold at Harlech Castle was captured and Owain Glyn Dwr retreated to the mountains, never to be seen again. The prince next led an army to France to exploit the anarchy there following the descent into madness of King Charles VI of France (r. 1380-1422), but the expedition came to nothing. Still, the prince was outshining his father and there developed some friction between the two, especially over the Prince's desire to take a more militaristic approach with their great rival France and resume in earnest the on-off conflict that is known to history as the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453).

Succession

Henry IV died of illness on 20 March 1413. The king's health had been in decline since 1406, and Prince Henry had already taken over some of the king's duties. Prince Henry, aged just 25, was crowned Henry V on 9 April 1413 in Westminster Abbey while a blizzard raged outside. The new king took his new responsibility seriously and banished all his old rollicking and roistering comrades from his presence, forbidding any of them to come within 10 miles (16 km) of his person. The king also sported what seems to modern eyes an unusual haircut but this was in the style of soldiers and indicated the king meant business when he said to his dying father that he would defend his crown with his sword.

The king would need his sword sooner than he thought when he had to deal with a murder plot in 1415, known to history as the 'Southampton Plot'. The plan was to put Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March and great-great-grandson of Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377) on the throne. The conspirators were led by Sir Thomas Grey; Henry, Lord Scrope of Masham; and the Earl of Cambridge, who was the grandson of Edward III. All three were executed in August 1415 after Mortimer had himself informed the king of the plot.

Henry was not merely a warrior king, though, and during his reign he encouraged the use of the English language in official documents and literature as opposed to the previously dominant French language. Another area of concern to the king was the medieval Church and the heresy of the 'Lollards'. These heretics believed that anyone could pray in private and so the Church as an institution need not be the bridge between God and humanity. Further, one of the Lollard exponents, the theologian John Wycliffe (c. 1325-1384), called for a redistribution of the Church's wealth, an idea taken up by members of the dangerous Peasants' Revolt of 1381. By persecuting the Lollards, putting down riotous Lollard demonstrations in January 1414, and even imprisoning for heresy his own friend Sir John Oldcastle, Henry thus acquired the full support of the Church, an indispensable ally when it came to gathering the cash needed for his planned military campaigns.

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War between England and France had started remarkably well for the English during the reign of Edward III. Aided by his son Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376), great victories were won at Crécy in 1346 and Poitiers in 1356. However, Charles V of France, aka Charles the Wise (r. 1364-1380), steadily regained the initiative and by 1375 the only lands left in France belonging to the English Crown were Calais and a thin slice of Gascony. Now, though, with the demise of Charles VI, the French nobles were divided and the country in chaos. In addition, the longbows used by English armies were still the most devastating weapon the medieval battlefield had yet witnessed. Henry IV and his son had disagreed over policy towards France and which faction to back: those led by the Duke of Burgundy (the Burgundians) or the supporters of the Duke of Orleans (the Armagnacs). Henry V was now keen to make good on his failed expedition in France when a prince and to take a much more decisive course of action against the old enemy.

With French pirates running riot in the English Channel and the chance of lands and booty in the event of an invasion of a teetering France, the majority of English barons and the Parliament were enthusiastic for action. Another helpful factor was the stability of the Welsh and Scottish borders. In order to win the support of any waverers, Henry reinstated the estates of those lords his father had been against and, in a show of conciliation with the wrongs of the past, had the body of Richard II re-buried in Westminster Abbey (from Kings Langley). With the country behind him, Henry was ready to pursue the claim that had started with Henry's great-grandfather, Edward III, the nephew of Charles IV of France (r. 1322-1328): the English king was also the rightful king of France. Even the royal coat of arms still showed the three lions of England and the fleur-de-lis of France.

Agincourt

To give himself time to assemble funds and his army, Henry made diplomatic advances towards both of the French factions in 1415. Nothing came of these discussions except, as the story goes, the son and heir of Charles VI, the Dauphin (another Charles), sent the young Henry a box of tennis balls with a note he should concentrate on sports rather than war. Henry showed his clear intent when, in mid-August, he invaded Normandy with an army of around 10,000 men and captured the port of Harfleur after a gruelling five-week siege. With winter around the corner and his force already depleted to 6,000-7,000 men by the fighting and a wave of dysentery, Henry decided to withdraw to English-held Calais and regroup.

The French had not been wasting time during this first part of the invasion and the Constable of France, Charles d'Albert, assembled an army of around 20,000 men to meet the enemy and overwhelm them with sheer numbers. The two armies met on Saint Crispin's day, 25 October 1415 near the village of Agincourt. The ground was in a shocking state for a battle and presented a field of mud for both sides. The English had lighter armour than their French counterparts and this proved very useful in the battle conditions. Yet again, though, it was the longbow that proved decisive as the English archers fired at the enemy from three sides. French knights were knocked off their horses and had their armour pierced by the powerful English arrows.

The French losses were astonishing: around 7,000 men to the English dead of perhaps as few as 500. The figures were so high for the French because Henry had ordered the execution of prisoners when a contingent of the enemy attacked the English baggage train in the rear and so the king feared the fighting might start anew. Amongst the fallen were most of the French nobility, including several dukes and counts, a situation which meant there was limited resistance to Henry's next moves in terms of large field armies clashing. The king had, once again, led his troops from the front and won, even if he had received a heavy bash to his helmet (which now hangs over his tomb in Westminster Abbey). The Duke of Orleans was captured at Agincourt and he eventually found himself a prisoner in the Tower of London for the start of his 25 years of confinement in England.

King-to-be of France

Between 1417 and 1419 Henry conquered Normandy by persistent siege warfare of strategically important cities and fortifications. Caen, for example, was taken in 1417 after a siege where no quarter was given by either side. Henry forbade his men from plundering but, despite once hanging an archer for stealing a small box from a church, this was difficult to always enforce. The king famously captured Rouen, the Norman capital, in January 1419 after a siege where the king's artillery batteries were used and a ruthless Henry ordered dead animals thrown into any wells which eventually caused so much disease in the town that it was forced to capitulate. Consequently, Normandy was now in Henry's control and land was parcelled out to loyal followers.

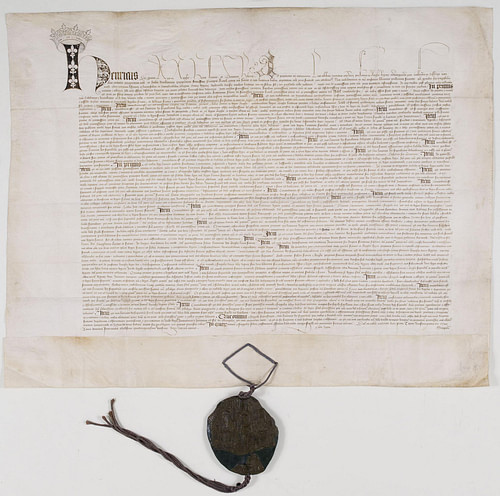

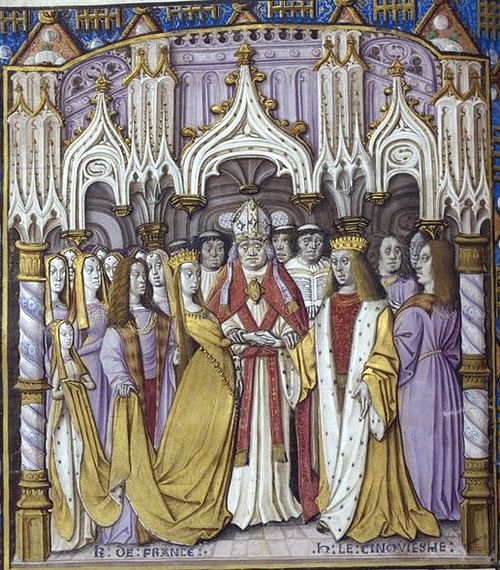

At the end of 1419 Henry set his sights on Paris. Supporters of the Duke of Burgundy, after the duke's father was murdered by a French rival, crucially gave their backing to Henry's claim to be ruler of France as well as England. This arrangement was sealed in May 1420 with the Treaty of Troyes. According to this treaty, Henry would be made the king of France following the death of Charles VI. The new regime would be tied to the old via the marriage of the English king to Charles' daughter Catherine of Valois (l. 1401 - c. 1437). Finally, Henry had to promise he would continue fighting against the Burgundian's number one enemy: the now disinherited Dauphin Charles.

On 2 June 1420 in Troyes Cathedral, Henry V did indeed marry Catherine and the war was resumed against the Dauphin. Henry was at the peak of his powers, the most potent ruler in Western Europe. In 1421, the royal couple returned to England where they were welcomed by a show of pageantry and choirs in the streets of London and Catherine had her coronation ceremony.

On 6 December 1421 at Windsor Castle Henry's only child was born, another Henry. The wheel of fortune was already turning for the English king, though. In March 1421, the English lost at the Battle of Baugé and Henry's own brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence was killed. Henry headed back to France to resume the war and so he never saw his son born or at any time thereafter. The king enjoyed one more success on 11 May 1422, capturing Meaux after an eight-month siege. Henry's career had been glittering, but it was also to be short.

Death & Successor

Henry died, probably of dysentery (although it may have been bowel cancer), aged 35, on 31 August 1422 at Bois de Vincennes in France. The English king had missed the chance to become the king of France by less than two months; Charles VI died on 21 October 1422. Henry's body was returned to England and buried at Westminster Abbey, and he was succeeded by his infant son, crowned Henry VI in November 1429, again in Westminster Abbey. The infant's regents had already been appointed by his father: Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (l. 1390-1447) for England and John, Duke of Bedford (l. 1389-1435) for France, both were brothers of Henry V.

Henry VI's reign turned out to be long, despite an interruption during the 1460s, but he could not stop a grand French revival which included the heroic efforts of Joan of Arc (c. 1412-1431) and the crowning of the Dauphin as King Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461). Henry had continued to press a claim for the French throne, eventually being crowned as such in the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris in December 1431, although loyalists to Charles VII disputed his right to do so. Henry VI, who suffered from bouts of insanity, met a sticky end, murdered in the Tower of London in May 1471 as the two houses of Lancaster and York battled for the throne in what later became known as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487).

Henry V's legacy might have crumbled quicker than he hoped, but he has at least gone down in history as one of England's great kings, a view which benefitted greatly from his heroic treatment by William Shakespeare (1564-1616) in his play Henry V (1599), which contains the following stirring lines, spoken by Henry to his army just before the battle of Agincourt:

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by

From this day to the ending of the world

But we in it shall be remembered,

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; but he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition.

And gentlemen in England now abed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap while any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

(Act 4, Scene 3)