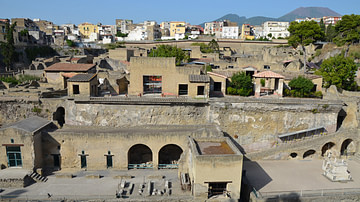

Herculaneum, located on the Bay of Naples, was a Roman town which was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. Like its neighbour Pompeii, the town was perfectly preserved by a metres-thick layer of volcanic ash which, in the case of Herculaneum, was then covered in a lava flow which turned to stone, preserving even organic remains. Multi-storeyed buildings, frescoes, papyri, and skeletal remains are just some of the excavated material which has helped archaeologists and historians piece together the daily life of a 1st-century CE Roman town. Herculaneum is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Pre-Roman History

Herculaneum was originally a town located on a spur of the volcano Mount Vesuvius just 8 kilometres (5 miles) southeast of Neapolis (modern Naples). The precise early history of the town is unknown, but it may have been established in the 6th or 5th century BCE as an offshoot or dependency of the Greek colony at Naples. The name and the presence of regular streets would further suggest such a link. Certainly in myth, as recorded by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (b. c. 60 BCE), the city was founded by the Greek hero Hercules as he passed on his way home from Iberia and his task of securing the herd of Geryones, one of his celebrated 12 labours. There was even a legend that Hercules had fought fiery giants hereabouts. Clearly, somebody somewhere knew that Mount Vesuvius had not always been the peaceful backdrop to the picturesque coast it had now become. Strabo (b. c. 64 BCE) states that the town changed ownership several times, being Oscan, then Etruscan, Pelasgian, and finally Samnite.

In the 4th century BCE, the town was Oscan and remained so for the next few centuries, at least in terms of culture, as attested by the presence of a marble altar to Venus inscribed in the Oscan language. Herculaneum prospered as a stopping point along the coast road which ran from Neapolis to Pompeii. Not insignificantly, given future events, the town was actually built on a terraced slope facing the sea, its very foundations being a giant lava flow and then ash layer from an eruption of Mount Vesuvius c. 6000 BCE and c. 1750 BCE respectively. The land was fertile as a consequence and the tuff stone an excellent source of building materials. Water was provided by a river running either side of the town coming down from Vesuvius, although these were only seasonal.

Roman Herculaneum

Herculaneum was a member of the Samnite League, but it then became an ally of Rome during the Social War (aka Italic War, 91-87 BCE). Rome was victorious and, thanks to Titus Didius in 89 BCE, took over the town. Herculaneum became a municipium, and the town's male population was granted Roman citizenship. The town's traditional Oscan institutions were, therefore, changed to Latin ones, and it was ruled by two magistrates (duumviri) who were elected annually. Other typical Roman officials included a quaestor who looked after the town's treasury and an aedile responsible for public spaces and their cleanliness.

Herculaneum traded with its neighbours and made good use of its small harbour but its limited hinterland meant that it could never grow to become a city comparable in size to Neapolis or even Pompeii. Like the latter town, Herculaneum was ideally placed to benefit from those richer Roman citizens from the capital and elsewhere that sought a pleasant place to escape from their daily lives. The town was seemingly a quiet resort with its fine weather and picturesque sea views, and it was easily reached by road. The shops appear modest and the town's streets show a distinct lack of wear from traffic (unlike those in busier Pompeii). The town had many varied types of housing which include large villas, smaller townhouses with second-floor balconies and tower blocks (insulae). There was a theatre, palaestra, forum, and basilica. Near the coast was a Roman baths buildings, the Terme Suburbane, strategically positioned to catch travellers as they came and went through the Porta Marina gate. The baths might have been quite small compared to other towns but they included a heated indoor swimming pool and were lavishly decorated with marble paving. The interior walls of the changing rooms have particularly striking erotic frescoes.

The wealth of some of Herculaneum's residents is attested by the presence of several Roman senators and many impressive 1st-century CE residences which were built on the domus model but with many rooms given panoramic sea views and terraced gardens. One such residence is the Villa of the Papyri. Located north-west of the town, the villa once boasted terraced gardens with water features and statues. The Villa of the Papyri is so named because a treasure trove of 1785 papyrus scrolls was discovered amongst its ruins which, although carbonised, have given up some of their secrets to restorers. Many of the papyri covered the works of the poet, historian, and philosopher Philodemus of Gadara (who probably died in the town) and were clearly part of a larger philosophical library with a strong Epicurean theme. No examples of Philodemus' prose works had survived antiquity until the discovery of the papyri at Herculaneum. The Villa of the Papyri was, in fact, the inspiration for the Getty Museum in Malibu, USA. Other villas at Herculaneum, such as the Villa dei Pisoni, have also been an important source of papyri, most of them written in Greek.

Vesuvius Erupts

Herculaneum was badly damaged by the earthquake which struck the area on 5 February 62 CE. This quake measured an impressive 7.5 on the Richter scale. Most private and public buildings were affected and, unfortunately, aftershocks and new but smaller earthquakes continued to create more damage over the next two decades. Emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) was even moved to fund some repairs, as did wealthy private citizens of the town, but it was an ominous forewarning that Vesuvius was building up for something big. There were other signs, too, that nature was restless. The ground level of the area subsided significantly, allowing the sea to encroach into parts of the town and cause some houses to be abandoned or their ground floors to be adapted. Mount Vesuvius had not significantly erupted for centuries and its familiar sight as a backdrop to the urban centre and its picturesque slopes all covered in trees and vines lulled the population into thinking the volcano was extinct, the mountain only ever a benign presence.

When it finally came, the eruption in 79 CE (sometime between August and October) was devastating. A massive explosion blew the top of the mountain off and a huge mushroom cloud of pumice particles rose 27 miles (43 km) into the sky. The power of the explosion has been calculated as 100,000 times greater than the nuclear bomb which devastated Hiroshima in 1945 CE. Soon ash began to float down and land lightly but persistently on the surrounding countryside. Most of the ash fell over nearby Pompeii, and it seemed that Herculaneum might be spared, the town receiving only a light dusting. Then the towering column that loomed above the volcano collapsed and a wave of 400 degree Celsius gases swept down over Herculaneum at a speed of 80 km (50 miles) an hour. Any living thing in its path was killed almost instantly.

The tragedy of this awful event is captured most tangibly in the form of skeletons of some 300 people who died at the harbour while trying to escape the chaos. Perhaps they had been waiting for boats that never came. The volcanic material spewed out by Vesuvius over the next few days, including surface lava flows, eventually buried these people and their town completely and this then solidified into tufaceous rock, preserving even organic material and, unusually, the upper stories of buildings (as often these were built using a wooden frame filled with rubble). The latter stage of destruction did not occur at Pompeii, which was buried in only ash and small stones, and so Herculaneum is, in many ways, an even better window into the lost Roman world of the 1st century CE than its now more famous neighbour. Unfortunately for archaeologists, it also means that Herculaneum is much more difficult to excavate. Beginning in the 18th century CE, tunnels were made into the town's rock covering - up to 25 metres (82 ft) deep in some places - but even today only a little more than a third of the whole urban site has been excavated, and many of the known sites such as the theatre and forum remain accessible only via the original excavation tunnels.

Artefacts & Continued Study

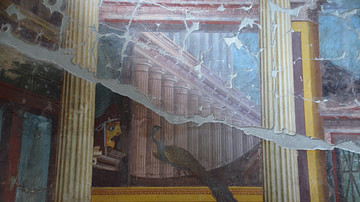

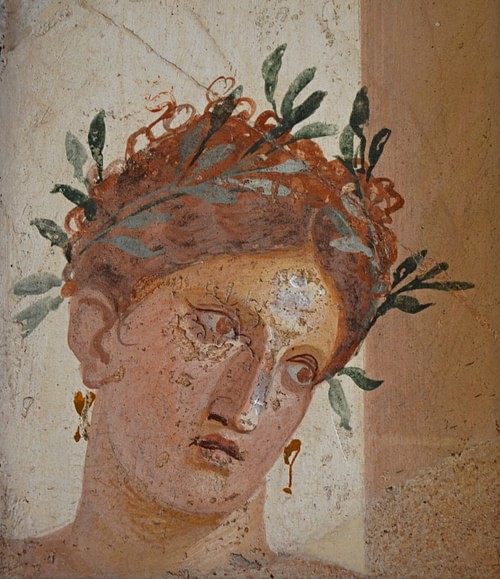

Artefacts discovered at Herculaneum, many of which are on display at the Archaeological Museum of Naples, include fresco wall paintings of daily life, mythological scenes, landscapes and local flora and fauna. Rare wooden artefacts include tables, beds, free-standing screens, and children's cradles. There are even examples of carbonised bread, one loaf carries the imprint 'Made by Celer, the slave of Quintus Granius Verus.' There are statues and figurines, including one of Isis encrusted with silver, examples of fine glassware - often either colourless or bluish-green, terracotta water spouts in the form of animals, and mosaics which decorated floors, walls, and fountains. An outstanding example of a Herculaneum mosaic is the scene with Neptune and Amphitrite from the villa of that name made using small pieces of coloured glass.

The town and its inhabitants continue to be studied today as excavations are ongoing and new technology permits ever-deeper analysis of such carbonised artefacts as papyri scrolls. Skeletal remains, in particular, can be examined in detail, and those from Herculaneum reveal that many people had to perform heavy physical labour from childhood and that their diet consisted mostly of vegetables and seafood. It is also possible to see that many males used their bodies in particular ways, for example, their teeth to hold nets while they rowed their fishing boats. There are surprising statistics, too, such as the small proportion of children compared to those remains found at Pompeii and the great genetic diversity showing that the community had individuals from across the ancient Mediterranean world. Finally, even the cause of death can be ascertained with those people on the beach dying of burning gases while those people who sheltered in the boathouses died from falling debris or by inhaling fine ash as they hoped to escape what would only become their tomb.