Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) was a Spanish conquistador who led the conquest of the Aztec Empire in Mexico from 1519. Taking the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521, Cortés plundered Mesoamerica as he became the first ruler of the new colony of New Spain.

Cortés was a gifted leader of men, and he seized every opportunity presented to him in the New World. Using superior weapons and tactics combined with diplomacy to supplement his meagre force of conquistadors with thousands of indigenous warriors, Cortés was able to sweep all before him. Initially rewarded by the Spanish Crown, Cortés soon found himself overwhelmed by a new wave of colonial administrators and constant legal battles where he faced charges of exceeding his authority, taking more than his due in loot, and using excessive violence and terror against indigenous peoples.

Early Life

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano was born in 1485 in Medellin, Extremadura, Spain. His parents belonged to the petty nobility, his father being a hidalgo. Hernán studied law at the University of Salamanca from 1499, but at 19 years old, he decided to leave Spain and try his luck in the Caribbean colonies. After running a plantation on eastern Hispaniola (Santo Domingo) and working as a notary in Azúa de Compostela, he decided to participate in the conquest of Cuba in 1511. Seven years later, and now in his mid-30s, he was itching for his stab at fame and glory. Perhaps not only out for gold, Cortés was a deeply religious man, and the spirit of evangelism, for him if not his followers, was an extra motivation to further open up this New World.

Two Worlds Collide

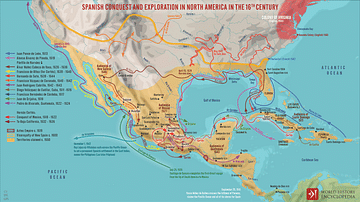

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465-1524), the Governor of Cuba, had already sent several expeditions to explore the mainland coast of America starting in 1517, and these had reported strange ancient stone monuments and brightly dressed natives from whom were bartered fine gold objects. The governor organised another expedition and chose as its leader Hernán Cortés, who had served him as the alcalde, or chief magistrate, in Santiago de Cuba. Eleven ships were packed with 500 soldiers and 100 sailors, all of them adventurers and treasure-seekers. At the last minute, wary of the scale of Cortés' preparations, Velásquez tried to recall his lieutenant, but it was too late. Cortés might have been the expedition leader but, as the historian S. Sheppard explains, this was most certainly going to be a group effort:

Cortés was not a general in command of a professional army, he was a gentleman who arrived at decisions only through the consent of other gentlemen. Throughout the campaign, his leadership had no more foundation than the very fragile status of first among equals that depended entirely upon vision, charisma, and success. (30)

Cortés was undoubtedly a charismatic and inspirational commander, and although he had little practical military experience, he was, crucially, a leader capable of taking both utterly ruthless decisions and extravagant gambles to maximise his opportunities in a fluid and constantly changing geopolitical situation. As Sheppard summarises: "A devout Catholic and inveterate bigamist, a crusader and an opportunist, a renegade and an imperialist, Cortés was a man of many contradictions." (21)

The Aztec civilization (aka Mexica) had flourished from c. 1345 in Mesoamerica, and by the 16th century, it came to cover most of northern Mexico, an area of some 135,000 square kilometres with a population of around 11 million. The Aztecs used military coercion, hostages, and the extraction of tribute to hold their fragile empire together, but they had not conquered everyone. The Tarascans and Tlaxcalans, in particular, continued to probe at the borders of their empire. The Tlaxcalans and other peoples would prove to be invaluable allies of the Spanish as they were only too keen to see the downfall of the Aztecs.

Cortés landed on the Tabasco coast at Potonchan on the Americas mainland in March 1519. The Old World was about to meet in person the current masters of Mesoamerica. Cortés and his men had no idea what they were about to face, but to make sure nobody entertained thoughts of going home, Cortés ordered the deliberate grounding and breaking up of his ships. It was now a case of conquer or die.

Superior steel and gunpowder weapons, cavalry, and dynamic tactics ensured easy Spanish victories against the hostile peoples they encountered. Mesoamerican weapons and armour were primitive compared to that of the Spaniards. The Mesoamericans had razor-sharp obsidian-bladed swords and clubs, bows, spears, and dart throwers, but these made little impact against metal armour. On the other side, Spanish steel swords, long pikes, crossbows, and gunpowder weapons were devastatingly effective against warriors protected only by padded cotton cloth and wooden shields. Cavalry proved itself almost invincible against any number of Mesoamerican attackers. Finally, tactics did not help the indigenous peoples, who were used to ritualised warfare where display and taking captives took priority. Mesoamerican officers were easily identifiable with their extravagant costumes, and these were the first targets of the Spanish. When the officers were killed, very often the rank and file fled in panic. Mesoamerican warriors did learn new tactics and focussed on ambushes on broken ground as a strategy to negate the strengths of cavalry, but the overwhelming military advantage, despite facing far superior numbers, remained in the hands of the Spaniards.

A significant bonus in these early encounters was the capture of Malintzin (aka Marina, Malinali, or La Malinche), a Maya woman who spoke the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs and a local Mayan language, which one of Cortés' men was familiar with. The invaders could now communicate with potential allies. Malintzin and Cortés had a son together, Don Martin. Cortés later had another son, also called Martin (his mother was Doña Juana Ramírez de Arellano, the daughter of a Spanish count from Cuernavaca), but it was his illegitimate child with Malintzin that Cortés favoured, accompanying him to Spain and ensuring he was invested as a knight in the prestigious Order of Santiago.

The Aztec ruler Motecuhzoma (aka Montezuma, r. 1502-1520) soon got news of these troublesome invaders, but he cautiously awaited developments. Cortés, meanwhile, established a garrison at Veracruz on the coast. He ignored instructions to return to Cuba and instead sent a quantity of the treasures he had acquired, with letters requesting royal support, to the king of Spain, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556). This was exceeding his authority since technically it was Velásquez who held the right of adelantado, that is to conquer territory in the king's name. A great furore ensued over the matter, which ended in Cortés, thanks to his treasure, being allowed to continue his conquest while Velásquez was removed from office. Meanwhile, back on the ground in Mexico, the conquistadors were marching inland by August 1519, first battling the Tlaxcala. Cortés then displayed his mastery of diplomacy and managed to persuade the Tlaxcalans to join him in his war against the Aztecs. The Spanish and their allies pressed on to Tenochtitlan in November.

Motecuhzoma & La Noche Triste

Located on the western shore of Lake Texcoco, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had over 200,000 inhabitants, making it the largest city in the Pre-Columbian Americas. It covered some 12-14 km² and was connected to the western shore of the lake and surrounding countryside by three causeways (running north, east, and west), which included gaps traversed by removable bridges to allow boats to pass.

The conquistadors were permitted to enter the city peacefully on 8 November, and they marvelled at its wonders of grand plazas, temple-pyramids, and floating gardens. When Cortés and Motecuhzoma met, initially, relations were friendly. Valuable gifts were exchanged between the two leaders. Cortés received a necklace of golden crabs, and Motecuhzoma a necklace of Venetian glass strung on gold thread and scented with musk. The Aztec ruler may have been wary of these visitors, having heard of their earlier military victories, but he seemed undecided what to do with them. Diplomacy, in any case, went out of the window two weeks later, when Cortés took Motecuhzoma hostage on 14 November. The Spanish wanted treasure, and the Aztec ruler was obliged to swear himself a subject of the king of Spain. There were other indignities like a crucifix being set up at the top of the sacred Aztec pyramid, the Templo Mayor.

Cortés now had his own problems, though. With his rivalry with Velázquez at that point unresolved, the governor of Cuba had sent a force under the command of Pánfilo de Narváez to Veracruz to apprehend Cortés. Cortés was obliged to leave Tenochtitlan and meet these competitors for future treasure, and so, in May 1520, he left Tenochtitlan in the hands of a small Spanish force under the command of Pedro de Alvarado. Alvarado and his men proved rather insensitive to Aztec conventions when they unwisely attempted to interrupt a ceremony of human sacrifice and then massacred members of the Aztec nobility. The Aztecs rose up and killed a number of the interlopers. Meanwhile, Cortés defeated Narváez and persuaded his remaining men to join him. They all returned to Tenochtitlan on 24 June, where a handful of Spaniards were still holding out.

In the still-bubbling hostilities, Motecuhzoma had been replaced by Cuitláhuac as the new Aztec leader after Cortés had foolishly released him from imprisonment. Cuitláhuac had immediately taken over rule of the Aztecs from his captive and now dishonoured brother. Cuitláhuac organised a total war against the conquistadors. When the Spanish tried to use Motecuhzoma to bring calm to the situation, the former leader was struck by a rock and killed on 30 June. The Spanish became trapped in the royal palace of Axayácatl. Cortés managed to flee the city in a running night battle on 30 June 1520. This bloody retreat became known as the Noche Triste ('Sad Night'). The Spaniards had extricated themselves using temporary wooden bridges built for the challenging task of crossing the city's many canals, but the price of freedom was high. Cortés had lost half his men, most of his best horses, and all of the eight tons of loot he had been accumulating ever since he arrived in Mesoamerica.

The Siege of Tenochtitlan

Before reaching the safety of Tlaxcala territory, Cortés first had to win a great battle near Otumba on 7 July, where the Aztecs tried once and for all to wipe out the foreign invaders. After several more campaigns, and receiving reinforcements by sea, several cities were captured, notably Texcoco on 31 December 1520. Cortés' plan was now to lay siege to Tenochtitlan, but already another, far more terrible enemy had swept through the Aztec population. There had been a devastating outbreak of smallpox in the previous September and November, which killed up to 50% of the population. The Aztecs also had a new leader, Cuauhtémoc, after Cuitláhuac himself had succumbed to the imported disease. In April 1521, Cortés began his siege. His force included 700 infantry, 118 crossbowmen and harquebusiers, 86 horses, and 18 field guns. Most significantly of all, the Spanish had native allies, including at least 100,000 Tlaxcalans.

Overcoming the deficiencies of their weapons, the Aztec warriors fought ferociously and with courage, as noted by the Spanish themselves. On 28 April 1521, Cortés deployed his trump card and logistical marvel: a fleet of 13 specially built warships on Lake Texcoco. These vessels, never before seen by Mesoamericans, were built from the great ships Cortés had ordered wrecked two years before and new supplies from Veracruz. They had been constructed prefabricated so that they could be transported by land to the lake. With these ships, Cortés was able to counter the many thousands of native canoes and block the three main causeways which linked the city to the edges of Lake Texcoco. Each brigantine carried 25 men plus six carrying crossbows and harquebusiers. The Spanish ships were escorted by a large fleet of canoes manned by their allies from Texcoco.

Through May and June, men, horses, and ships persistently attacked the Aztec positions, forcing them into an ever-smaller core group within the very centre of Tenochtitlan. In one battle, Cortés was himself briefly captured before his men rescued him. Others were less fortunate and found themselves sacrificial victims. Still, Cortés persisted, systematically blowing up buildings as he tightened the siege. Finally, on 13 August, after 93 days of resistance and long out of food and weapons, Cuauhtémoc surrendered. Indescribable atrocities, acts of revenge, and wild looting then followed.

From the ashes of the disaster at Tenochtitlan rose the new capital of the colony of New Spain, and Cortés was made its first governor in May 1523. The capital had fallen, but the Spanish were required to campaign in other parts of the crumbling Aztec Empire until 1525. Cortés had personally led a campaign against the Huaxtecs in 1522. As the Mesoamerican way of life was systematically repressed, and land was parcelled out to the conquerors, Tenochtitlan, with its great lake drained off, gradually morphed into Mexico City, capital of the Viceroy of New Spain, now headed by Don Antonio de Mendoza.

Honduras

Cortés might have delivered a great prize to the Spanish Crown, but he struggled for recognition in the longer term. Soon tiring of administrating, he returned to exploring and conquest in 1523-4, when he organised an expedition to Honduras led by Cristóbal de Olid (b. 1492). De Olid was a long-time companion of Cortés', but, in league with Diego Velázquez, he betrayed his old commander and set himself up as the independent ruler of Honduras. Cortés responded by sending Francisco de las Casas to find and arrest Olid for treason but then thought better of it and departed Mexico City for Honduras himself in October 1524. The land route was a difficult one as it crossed Guatemala, as yet wild and uncharted territory. By the time he got to his destination, Cortés discovered that Olid had already been tried and executed. Cortés then established the new town of Navidad de Nuestra Señora, introduced livestock to the area, and appointed a governor.

Death & Legacy

Cortés next spent time back in Spain, arriving in May 1528 with treasures and 40 Aztecs to wow the court. He persuaded Charles V to grant him great estates in the Americas, the title of Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca, and the right to keep one-twelfth of any wealth he acquired. However, Cortés was already becoming a part of history. The now aged and few surviving conquistadors who had risked all for glory had been replaced by professional bureaucrats and evangelising priests. When he returned to Mexico City in the summer of 1530, Cortés was barred from his own mansion by the new governor Gonzalo Nuño de Guzmán (d. 1558). Cortés was obliged to live in his second residence in Cuernavaca. He also became embroiled in many lawsuits from his rivals and former followers who were convinced their leader had taken much more than his fair share of loot during the conquest. There were also cases to be answered for his mistreatment of indigenous peoples, which ranged from the callous mutilation of peace envoys to wholesale massacres.

Fortunately for Cortés, there were still a few pockets of unknown territories, and Charles V had promised him he could be "governor of the islands which he might discover in the South Sea [Pacific Ocean]" (Cervantes, 240). In the early 1530s, then he left behind all the red tape of New Spain and led an expedition to explore the Pacific coast of Mexico and perhaps find the route to Asia and the Spice Islands Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) had been looking for. Cortés sailed to the north as far as the peninsula of Baja California, and, thinking this an island, he named it Santa Cruz. In 1540, he returned to Spain, and undeterred that he was now in his mid-50s, Cortés campaigned for the Spanish Crown in Algeria in 1541.

Hernán Cortés died of dysentery in Castilleja la Vieja in Spain on 2 December 1547. The great adventurer had been about to depart again for the New World. In his will, the conquistador had expressed a desire to be buried in the land he had conquered, specifically a monastery in Coyoacán. These wishes were ignored, and his remains were interred in a monastery outside Seville. Then, in 1556, Cortés' remains were moved to the church of San Francisco de Texcoco in Mexico. Hardly resting in peace, the remains were later moved to a palace and then to a Franciscan church in Mexico City. In 1794, Cortés was on the move again when his bones were interred in the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno of Mexico City and then moved again in the 19th century to a nearby church, the Jesús Nazareno e Immaculada Concepción, where they rest today. Cortés' titles were inherited by his youngest (and only legitimate son), who became the Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca and so owner of a vast encomienda.

Hernán Cortés was regarded as a hero in his own lifetime, a man who had conquered new lands, brought riches for the Crown, and swept away a pagan religion that involved human sacrifice on a massive scale, paving the way for the further spread of Christianity. In more modern times, like all conquistadors, Cortés is now regarded more soberly as an opportunist and imperialist whose thirst for gold and taste for evangelism contributed to the systematic destruction of Mesoamerican culture, a man who was personally responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of indigenous peoples.