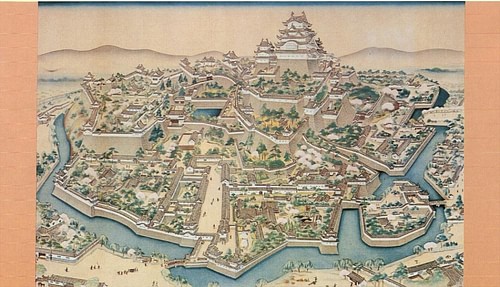

Himeji Castle, located in the town of Himeji in the Hyogo Prefecture of Japan, was built on a natural hilltop between 1581 and 1609 CE. The complex is composed of a maze-like arrangement of fortified buildings, walls, and gates, with a six-storey tower keep at its centre. The whole complex is surrounded by defensive walls and a double moat. The castle is the largest and best-preserved samurai fortification in the country and is both an official National Treasure of Japan and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Foundation & Function

The hill upon which Himeji Castle was built was first fortified in 1333 CE. The famous castle was added to the site in 1581 CE by the military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598 CE) who added the first version of the castle keep (tenshu) which then had only three storeys. This type of castle, built on a hill and surrounded by a wide plain, is known as hirayamajiro.

The castle was remodelled between 1601 and 1609 CE by the daimyo or feudal lord, Ikeda Terumasa (1564-1613 CE), and the keep was made even taller. This is largely the form we can see today although some outbuildings were added to the site in 1618 CE. Himeji Castle, like other medieval castles elsewhere, functioned as a private residence, a garrison for troops, an armoury, an administrative and political centre, a place where the arts could be created and appreciated, and as a symbol of power and prestige for its builder and resident lord. The castle not only controlled the surrounding countryside but also protected the western approach to the then capital Heiankyo (Kyoto).

Design & Defensive Features

The castle is surrounded by two water-filled moats (hori), although there were originally three. Once past this first line of defence, would-be attackers would then have to negotiate the surrounding fortification walls. The walls have a total length of 4.8 km (3 miles) and some sections reach a height of 26 metres (85 ft). Such was the prodigious quantity of stone required to build the walls one can still see today that sometimes desperate measures were taken and everything from tombstones to millstones were used in some sections. Despite the eclectic material, the walls have no mortar so as to make them more resistant to earthquakes. Besides their great height, the walls and buildings have the additional defensive feature of over 1,000 loopholes (sama) through which the defenders could fire on any attackers using arrows (the rectangular windows) and firearms (triangular portals). A final defensive feature was to cover the walls in a white plaster which made them resistant to fire.

There were originally 84 gates outside and within the castle, but only 21 survive today. The weakest part of any castle are the gates, but at Himeji Castle, these do not lead directly into the castle compounds. Instead, the gates take one through a series of zigzag paths where there might eventually be another gate or walls with a fortified top from which defenders could fire down upon attackers. Some passages even lead to a dead end. At Himeji, attackers had to essentially perform a giant spiral starting from the main outer gate (otemon) and pass through another eight heavily fortified gates before they arrived at the castle's keep. At one point they would have to turn 180 degrees to meet the next gate and twice they would need to pass through a long narrow stretch where walls on either side allowed the defenders to shoot at will on the enemy force, which, at this point, would have been obliged to proceed almost in single file.

The idea behind this maze of defensive features was not just to confuse the enemy but also to provide pockets of easily defended positions from which counterattacks could be launched to retake that area of the castle the attackers had already infiltrated. The main gate and the smaller gates were closed using a strong wooden door and crossbeam. Many of these doors have iron plating to make them more resistant to attack. Consequently, even getting through a gate would be a tough exercise and, assuming the attacking force did not get lost or eliminated by defensive fire, it would take a great deal of time and effort to finally reach the keep where they would then find the lord and main garrison of the castle.

The interior of the castle is composed of some 83 buildings surrounding the six-storey castle keep. If an attacking force decided not to attack via the gates but go through the buildings themselves they would be presented with further problems. This is because the castle complex has various interlocking courtyards and a deliberately confusing layout. There are also many long and narrow corridors which would slow down an infiltrating force and in many of them, there are holes in the ceilings through which missiles or boiling liquids could be rained down on the enemy. There are, too, hidden guardrooms from where defenders could spring out upon the castle's attackers. Even getting into a building would be very difficult since they have massive stone foundations. These inwardly sloping walls (ishigaki) provide both a structural function as retaining walls and a formidable climbing challenge for attackers.

The Castle Keep

The huge keep rises to a height of 46 metres (150 ft) from the centre of the castle's inner courtyard (hommaru). The keep is an example of the connected tower structure seen in Japanese castle architecture where the main tower is connected via passageways to several subsidiary towers (yagura). Two huge wooden columns and a massive stone foundation give the tower structural support. Although the inside of the tower has six floors and a basement, it appears from the outside as if there are only five floors because the fourth and fifth floors appear merged. The lowest floor is equipped with large drop holes set into overhangs at the corners of the structure through which the defenders could drop unpleasant things on any attackers. The roofs elegantly mix two traditional types of gable; the curved kara hafu and the triangular chidori hafu. The tower's combination of a pure white facade and aesthetically pleasing design of lifting pagoda roofs has given Himeji Castle the nickname 'The White Egret Castle' (shirasagijo).

Later History

Despite having all its impressive defensive mechanisms, or perhaps even because of them, the castle has never actually been attacked. Indeed, Himeji Castle has enjoyed a somewhat charmed, if at times risky, later history. First of all, it greatly benefitted from the relatively stable political situation of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868 CE). Then the complex was fortunate to survive the trend to dismantle the old feudal castles of Japan during the Meiji Period (1868-1912 CE). It was sold via auction in 1871 CE but remained intact despite plans floating around to entirely redevelop the property.

In 1931 CE parts of the complex were collectively listed as an official National Treasure of Japan, and it luckily survived the ravages of Allied bombing during the Second World War (1939-1945 CE) when the surrounding area was targetted. The castle was actually hit by a bomb but it failed to explode.

The castle has made many appearances on the silver screen, perhaps most famously in the James Bond film of 1967 CE, You Only Live Twice. Since 1993 CE, the castle has been listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site and so its security now seems guaranteed. There remains the threat from earthquakes, but the castle managed to survive the Great Hanshin earthquake of 1995 CE. Finally, the castle benefitted from a lengthy restoration project, completed in 2015 CE, and it is today the most visited castle in Japan.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.