Hobbamock (d. c. 1643, also given as Hobbamok and Hobomok) was a Native American of the Pokanoket tribe who served the sachem Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661) of the Wampanoag Confederacy as a pniese (counselor and elite warrior). He is best known for exposing Squanto's plot to undermine Massasoit's authority and set the pilgrims at Wampanoags against each other.

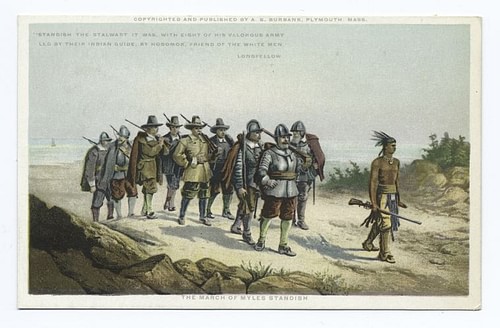

After the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty of 1621, Hobbamock was sent by Massasoit to live among the settlers of Plymouth Colony, most likely to keep watch over Squanto (l. c. 1585-1622), whom Massasoit and Hobbamock both distrusted, as much as to monitor the activities of the colonists themselves. Nothing is known of his life prior to 1621. He became close friends with Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656), the military commander of the colony, with whom he bonded as a fellow warrior, and eventually came to live with Standish on his farm in Duxbury, modern-day Massachusetts.

He is mentioned by the two chroniclers of the colony, William Bradford (l. 1590-1657) and Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655) in Mourt's Relation (Bradford and Winslow, published 1622), Good News from New England (Winslow, published 1624), and Of Plymouth Plantation, (Bradford, published 1856) as taking part in significant events between 1621-1628, and he continued to assist Standish in various military actions afterwards.

He is overshadowed by the better-known Squanto, to whom both Bradford and Winslow devote far more time, even though he lived among the colonists longer, proved himself more faithful both to their cause and that of Massasoit, and is the only Native American known by name to have befriended the Plymouth Colony long-term out of actual affection, having nothing to do with a treaty or personal gain. Although, like Squanto, he was originally ordered to the settlement by Massasoit, his friendship with Standish was genuine and encouraged him, as well as his family, to remain voluntarily until his death.

Name as Epithet

Hobbamock may have been an epithet of respect as it was the name of a powerful healing deity of the Native Americans of the region. The English colonists, only able to understand Native American religious beliefs according to their own, interpreted the supernatural entity Hobbamock as the devil when, actually, the natives had no concept of anything like the Christian devil.

Winslow himself admits to this mistake, writing, “Whereas myself and others, in former letters (which came to the press against my will and knowledge) wrote that the Indians about us are a people without any Religion or knowledge of any God, therein I erred” (Good News, 102-103). Even so, while recognizing that Native American religion was quite different than they had at first thought, they still characterized the Hobbamock deity as evil. Winslow, after describing the “Good Spirit” Kiehtan (the creator god who also presides over the afterlife), goes on to discuss the entity he interprets as that god's adversary:

Another power they worship, whom they call Hobbamock, and to the Norward of us, Hobbamoqui; this as far as we can conceive is the Devil, him they call upon to cure their wounds and diseases. When they are curable, he persuades them he sends the same for some conceived anger against them, but upon their calling upon him can and doth help them. But when they are [in danger of death] and not curable in nature, then he persuades them Kiehtan is angry and sends them, whom none can cure [to their death] in so much as in that respect only they somewhat doubt whether he be simply good and therefore in sickness never call upon him. This Hobbamock appears in sundry forms to them, as in the shape of a Man, A Deer, a Fawn, and Eagle, etc, but most ordinarily as a Snake! He appears not to all but the chiefest and most judicious amongst them, though all of them strive to attain to that hellish height of honour. (Good News, 104-105)

Although Winslow made an effort to understand and relate to Native American culture, he could not grasp a belief system different from his own any more than any of the other early English colonists who wrote on Native American religion. Scholar Lewis Spence relates an earlier instance in which a Christian missionary insisted Hobbamock was the devil:

When, in 1570, Father Rogel commenced his labors among the tribes near the Savannah River, he told them that the deity [Hobbamock] they adored was a demon who loved all evil things and they must hate him; whereas his auditors replied that, so far from this being the case, he whom he called a wicked being was the power that sent them all good things, and indignantly left the missionary to preach to the winds…[Hobbamock], so far from corresponding to the power of evil, was…the kindly god who cured diseases, aided them in the chase, and appeared to them in dreams as their protector. (105)

The entity Hobbamock seems to be more of a “trickster” god who encourages transformation and change than anything else and, in his role as protector, guide, and healer, his name was most likely given to the warrior Hobbamock who is described as a great pniese, a member of the elite, bodyguard and counselor to the chief.

Hobbamock the Pniese

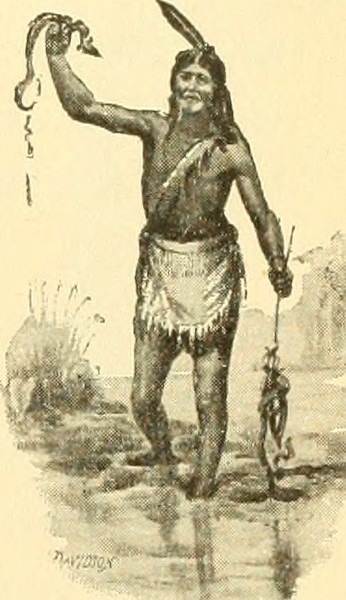

The pniese among the Wampanoag Confederacy would equate to the European concept of a noble knight. Winslow describes this class of warrior:

The pniese are men of great courage and wisdom [who cannot be killed in battle owing to supernatural protection]. And though [before] their battles, all of them by painting disfigure themselves, yet they are known by their courage and boldness, by reason whereof one of them will chase almost an hundred men, for they account it death for whomsoever stand in their way. These are highly esteemed of all sorts of people and undertake any weighty business. In war, their sachems, for their more safety, go in the midst of them. They are commonly men of the greatest stature and strength and such as will endure most hardness, and yet are more discreet, courteous, and humane in their carriages than any amongst them, scorning theft, lying, and the like base dealings, and stand as much upon their reputation as any men. (Good News, 106-107)

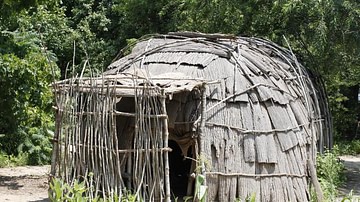

A pniese was chosen and trained from youth in strength of mind, body, and character, enduring hardship, abuse, privation, and abstaining from luxuries prior to an initiation ceremony during which they purified themselves and then left the village for a time to prove themselves alone in the wilderness. Winslow mentions three classes among the Wampanoag Confederacy generally and the Pokanoket tribe specifically who were the wisest and most respected, claiming he does not know the name of the first but the second two are the powwows (shamans) and the pniese.

Hobbamock is routinely described as an exemplary pniese and the right-hand man of Massasoit. He was entrusted with collecting the tribute owed to the Wampanoag from other tribes in the region and was considered so powerful that none would stand against him in battle. His position among the Wampanoag means he was almost certainly present alongside Massasoit at a number of recorded events, even if he is not mentioned by Bradford and Winslow, and one of these was the peace treaty of 1621.

Peace Treaty of 1621

The Wampanoag Confederacy was the most powerful political and military organization in the region prior to the arrival of European ships in New England but, between c. 1610 - c. 1619, European diseases wiped out many of the Native Americans, greatly reducing Massasoit's power. In their weakened state, they were attacked first by the Mi'kmaq tribe, then the Pequots, and finally the Narragansett tribe who, living further inland, had not been affected by European diseases. By the time the Mayflower arrived in November 1620, the Wampanoag had lost their former standing and were forced to pay tribute to the Narragansett.

At first, Massasoit instructed his powwows to enact rituals to destroy the new arrivals or drive them away through supernatural means and then asked for a sign and divine assistance to do so himself, but it seemed the spirits had another purpose in mind for the Wampanoag and the colonists. Squanto, a member of the Patuxet tribe which had been killed off almost entirely by disease and had been kidnapped in 1614 to be sold into slavery and only recently returned, was taken in by Massasoit – possibly as a prisoner – and seems to have suggested that the colonists could serve the chief's purposes as an ally to regain his former standing.

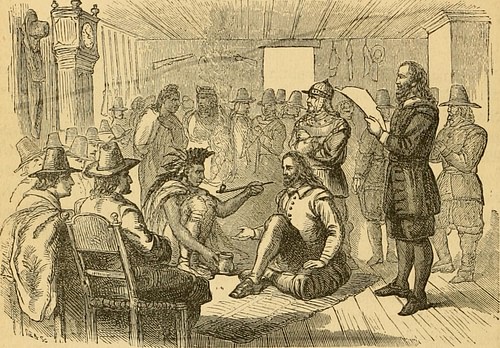

Massasoit sent an envoy, the Abenaki chief Samoset (l. c. 1590-1653), reportedly also a prisoner, to the colony on 16 March 1621 to see if they were friendly and might be interested in negotiating a treaty. Samoset's mission was successful and, on 22 March 1621, Massasoit came with his entourage, which would have included Hobbamock, and the treaty was worked out and signed. Squanto was ordered to remain with the colonists and teach them how to plant crops and, basically, survive, and a short time later, Hobbamock was sent to watch over Squanto and keep Massasoit informed of developments in the settlement.

First Thanksgiving & Squanto's Treachery

Hobbamock and Massasoit distrusted Squanto because he had been among the English so long, knew their language well, and there was no way either of them – nor anyone else – could tell whether he was interpreting truly and serving their interests or his own. Squanto performed the duties Massasoit had given him, helping the colony establish itself so that they were self-sufficient by the summer of 1621. Sometime later, Squanto and Hobbamock were sent on a trading mission to the interior, and Hobbamock returned to the colony alone, with the report that Squanto had been taken prisoner, along with Massasoit, and Squanto may have been killed.

Hobbamock explained how he had escaped just as a knife was being placed to Squanto's chest and he feared the worst. He led a party of militia, commanded by Standish, back to the village where they found Squanto and Massasoit had escaped on their own, but his action on the part of the colonists was commended as they had come to rely heavily on Squanto as well as their treaty with Massasoit. By this time, if not earlier, Hobbamock had learned enough English to be able to communicate with the settlers and was relied upon almost as much as Squanto.

That September (or possibly October), the colony held a harvest feast now known as the First Thanksgiving which was attended by Massasoit and 90 of his warriors. There is nothing in the primary documents to suggest they were invited, and most likely they were out on another mission, heard the sounds of musket fire (the colonists had discharged some arms in celebration), and came to see if they needed help, as per the conditions of the treaty. Hobbamock is not mentioned at this gathering but would have been there either as one of the entourage or because he was still living at Plymouth.

Although Squanto is regularly depicted in tales of the Plymouth Colony and the First Thanksgiving as the “friendly Indian” who helped the pilgrims, he was actually working for his own ends between 1621-1622 to undermine Massasoit's authority and take his place. On missions to various Wampanoag villages, Squanto told the people that the pilgrims kept the plague stored in barrels under their homes and could unleash it at will; for a price, he told them, he could put in a good word for them and keep them safe. Hobbamock was the first to discover Squanto's schemes when he overheard him telling other natives this story, and instead of confronting him, he asked the colonists about it and then revealed what Squanto had been saying.

Shortly after this, Squanto launched an initiative whereby he got Standish and Hobbamock out of the way on a trade mission and then had one of his relatives appear, looking beaten and bloodied, at Plymouth telling the colonists that he had just barely escaped from Massasoit who was coming to attack the settlement. Bradford had the cannon fired in hopes of bringing Standish's party back, which worked, and Hobbamock and Squanto were both asked about the attack.

Hobbamock told them that Squanto's relative was lying because, if Massasoit had been planning anything, Hobbamock would have known of it first. Hobbamock's wife was sent to Massasoit's village to see if there were any preparations for war and reported back there were none. Squanto's treachery was exposed and, though he was rebuked by Bradford, nothing else was done.

Massasoit, when he heard about Squanto, demanded he be handed over for execution but Bradford refused, citing how valuable he had become to the colony. Bradford had no legal right to do this, however, and the treaty was strained as Massasoit and his warrior-envoys were disappointed in the decision. Whether Hobbamock remained at Plymouth at this time is unknown – he is not mentioned in the narratives – but the problem was resolved when Squanto died, of fever according to Bradford, in 1622. It is possible he was poisoned by agents of Massasoit who sought to deal with the traitor without jeopardizing the Wampanoag's relationship with the colony.

Military Actions & Massasoit's Illness

After word of the success of Plymouth reached England, more colonists arrived, and one group established a settlement at nearby Wessagussett. This all-male company had been poorly provisioned, had no skill at farming, and soon took to stealing food from the Nauset tribe. In time, the relationship between the natives and the Wessagussett settlement deteriorated, and word reached Plymouth that an attack was planned, first on Wessagussett and then on Plymouth to prevent reprisals.

Hobbamock was either back in Plymouth at this time or had never left and went with Standish and the militia on a raid on Wessagussett during which a number of natives were killed. Although Bradford had approved the raid, he regretted the deaths and the aftermath during which other tribes refused to trade with Plymouth for a time. Hobbamock and Massasoit, however, approved of the action as sending the appropriate message that the Plymouth colonists were not to be trifled with.

Massasoit had profited handsomely from the treaty with Plymouth and was again in a position of power but, in March 1623, he fell ill and was thought to be dying. Hobbamock went with Winslow on a mission to pay the last respects of the colony to the chief, but Winslow used Native American remedies and his own knowledge to cure not only Massasoit but others in the village who were suffering from the same sickness. Winslow, in his Good News from New England, records Hobbamock's speech at this time eulogizing Massasoit as the greatest chief he had ever known. Winslow repeats this speech as reflective of Hobbamock's own values of virtue, honesty, justice, courage, and personal honor.

Hobbamock continued to serve with Standish throughout the 1620's and was part of the famous (or infamous) raid on the settlement of Merrymount. Merrymount was a far more liberal colony than Plymouth and its leader, Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647), encouraged a blend of Native American, English Christian, and pagan cultures. Colonists intermarried with natives and celebrations such as Mayday were held; the town square featured a large Maypole for this purpose. The Plymouth colonists objected to the “debauchery” of Merrymount, which they claimed included selling weapons to Native Americans, and Standish and Hobbamock led the raid which captured Morton, destroyed the Maypole, and more or less ended the colony in 1628.

Conclusion

Standish helped establish the nearby town of Duxbury in 1635 and retired to a farm he built there where he lived with his family and Hobbamock, with his family, for the rest of his life. Hobbamock died c. 1643 from disease, presumably picked up from close contact with the English, although, for this claim to make sense, it would need to account for why he had not gotten sick earlier since, by this time, he had been among the English for over 20 years. Standish buried his friend on the grounds of the farm but the location of the grave is unknown.

Hobbamock, though as integral to the survival of the Plymouth Colony as Squanto, has been largely forgotten in United States history outside of scholarly works on the subject. There is little or no mention of the great warrior during the annual season of Thanksgiving celebrations, and it is only in the past ten years that he has been featured in shows such as Saints & Strangers or American Experience: The Pilgrims, both from 2015.

Even so, his role as a Wampanoag pniese was significant, certainly during his time with the colonists but long before as well. He was already established as Massasoit's most trusted warrior and advisor prior to 1621 and, whatever his given name was, came to be known by that of the divine force of protection, guidance, and healing for a reason. What that reason was, like so much of Native American history, has been lost but Hobbamock's name and the strength of his character is preserved and his story is increasingly becoming recognized as just as important as other, better-known figures from American history.