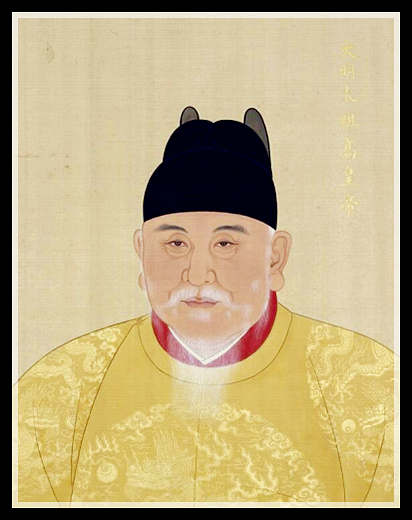

The Hongwu Emperor (r. 1368-1398 CE) was the founder of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE) which took over from the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1276-1368 CE) as the rulers of China. Born a peasant with the name Zhu Yuanzhang, the future emperor led a rebel group called the Red Turbans and seized the Yuan capital of Nanjing. Having defeated his rivals, Yuanzhang declared himself emperor with the reign name Hongwu in 1368 CE. Hongwu would oversee a resurgence in Han Chinese power and establish a dynasty that saw unprecedented economic growth and a flourishing of the arts. A harsh ruler who centralised government and reformed the ailing agricultural system of China, Hongwu ruthlessly dealt with any dissent at his court, executing thousands during his many purges. Probably not much loved by anyone, the emperor at least set the foundations for his successors to build upon and transform China into a world powerhouse. The emperor's posthumous name, to which sacrifices were made in his honour, is Ming Taizu.

Early Life

Hongwu's story was a classic rags-to-riches fairytale. The rags part might have been long and harsh but at least when he got to the riches part he would remain one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the world for 30 years. Born in 1328 CE in Anhui province, eastern China, with the name Zhu Yuanzhang, the future emperor's peasant family suffered extreme poverty, and his parents often found themselves having to move home just to avoid rent collectors.

An even greater disaster struck with the plague that hit China in the 1340s CE. Both his father and eldest brother succumbed to the disease, and the family was left penniless. By now 16 years of age, Zhu was obliged to join a Buddhist monastery, where at least he could find food and shelter. Unfortunately, the monastery was not doing too well either, and Zhu was obliged to sometimes beg in the street for his daily bread. The young man roamed around central China for several years, but he did eventually return to the monastery in Anhui. Zhu's flirtation with Buddhism allowed him to learn to read and write but it did not prevent him from later adopting Confucian principles; he would even write his own edition of the book of Mencius (372-289 BCE), the famed Confucian scholar.

The Red Turbans & Fall of The Yuan

The Yuan dynasty had ruled China since the Mongol invasions of the third quarter of the 13th century CE, but it was steadily losing its grip on control. Beset by famines, plagues, floods, widespread banditry, and peasant uprisings, the Mongol rulers, crucially, squabbled amongst themselves for power and failed to quash numerous rebellions. One of the most successful rebel groups was the Red Turban Movement.

The Red Turbans, so called because their members wore that colour headgear, was actually an offshoot of the radical Buddhist White Lotus Movement. The Reds had sprung up as part of the wider peasant reaction to the Yuan's policy of using forced labour on government construction projects, especially on the Grand Canal and Yellow River. Most active in northern China, the rebels frequently clashed with Mongol forces, and in one such episode, the monastery where Zhu was staying was burned down.

Zhu, now 24 and not having many other options, decided to join the Red Turbans. Slowly he made himself more and more vital to the cause. He married the daughter of one of the movement's leaders and then took over their leadership himself in 1355 CE. Establishing his power base in the Yangzi valley, Zhu eventually had 20-30,000 men under his command. Zhu replaced the Red Turban's traditional policy aim of reinstating the old Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) with his own personal ambitions to rule and he gained wider support by ditching the anti-Confucian policies which had alienated the educated classes. Alone amongst the many rebel leaders of the period, Zhu understood that to establish a stable government he needed administrators, not just warriors out for loot.

Zhu Yuanzhang Seizes Power

Zhu Yuanzhang's first major step to dominance in China was the capture of Nanjing, the Yuan dynasty capital, in 1356 CE. The Mongol rulers had not helped their cause by dismissing their most able general, Chancellor Toghto, the year before on the grounds that he was too pro-Chinese. Zhu's successes continued, and he defeated his two main rival rebel leaders and their personal armies. First to go was Chen Youliang, who had declared himself Han emperor in 1360 CE. Chen was killed and his army defeated at the battle of Poyang Lake in 1363 CE. Next came Zhang Shicheng, a salt smuggler and pirate with a large naval force, who was defeated in 1367 CE. When Han Lin'er then died - he who had claimed to be the rightful heir to the line of Song emperors - Zhu was left the most powerful leader in China, and, after chasing the remnants of the Mongol army back to Mongolia, he declared himself emperor on 23 January 1368 CE, the day of the New Lunar Year.

Zhu would take the reign name Hongwu (meaning 'abundantly marital') and the dynasty he founded Ming (meaning 'bright' or 'light'). The new emperor sought to establish his legitimacy by reinstating the traditional sacrifices Chinese rulers made to Heaven and Earth. For the same reason, other Confucian and Buddhist rituals saw a return, too. Whatever his legitimacy, Hongwu would stamp out any lingering rebel movements in the next two decades and reign until 1398 CE. His successors continued his efforts to unify China through a strong centralised government and so consolidate the Ming dynasty's grip on power. It was the beginning of another golden era of Chinese history.

Government Policies

Hongwu was wary of losing his throne in the same violent way he had gained it and so he was determined to impose a strong centralised government on China, with him personally exercising control over all matters. The institution of the Chinese emperor would return to that of old - the absolute monarch and possessor of a divine mandate to rule, the so-called Mandate of Heaven. To strengthen his position, even the Secretariat, which had previously acted as a bureaucratic limit on an emperor's power, was abolished (although not until 1380 CE and it would return under later emperors). Any dissenting officials were ruthlessly punished or executed, and to ensure Hongwu's control spread far beyond the capital in Nanjing, the provincial governments were reorganised with imperial family members placed at their heads. At the same time, local authorities were given just enough autonomy that they could create a balance of power with these regional heads and so ensure no one - family, friend or foe - ever rose to challenge the emperor.

Other policies carried out by Hongwu included the compilation of a draconian law code (the Da Ming lü or Grand Pronouncements); land and tax obligations were meticulously registered, hereditary military service continued to be imposed on the peasantry in threatened regions (as it had been under the Mongols), international trade was curbed as all things foreign were considered a threat to the regime, and the old tribute system required of neighbouring states was revived.

The reduction in commerce compared to the more internationally-minded Mongols meant that agriculture was once more the focus of government economic policy. Following the devastation of large swathes of China after the Mongol invasion and the rebellions during the Yuan's death throes, land for cultivation was meticulously registered and redistributed back to the peasantry, areas were drained, irrigation systems were improved, and some areas were reforested. The region of the south-west was conquered, and a new province was created; Guizhou.

The emperor, himself a beneficiary of free Buddhist education, was an advocate of learning for all, and he promoted local schools to that end. In 1370 CE, Hongwu reintroduced the traditional civil service examination system, which had been an essential path of social progression in pre-Mongol China and which would continue right into the 20th century CE. Regarding the arts, a flourishing would only really occur under Hongwu's successors but he did found a painting academy at Nanjing.

The Paranoia of Power

Perhaps initially more a hyper-paranoid ruler with some good intentions than an evil despot per se, Hongwu had no qualms about punishing his officials, as this quote attributed to him illustrates:

In the morning I punish a few; by evening others commit the same crime. I punish these in the evening and by the morning again there are violations. Although the corpses of the first have not been removed, already others follow in their path…Day and night I cannot rest.

(quoted in Brinkley, 168)

As time wore on, though, Hongwu became more erratic and more paranoid. Regular punishments and purges of the state bureaucracy were carried out, most infamously in 1376 CE when several thousand officials were executed following accusations of mismanaging the grain tax. Anyone who took exception to the emperor's bias towards Buddhism was similarly dealt with. From 1380 CE there was an even bigger purge which saw 15,000 officials and their relatives executed when Hongwu thought he had discovered an assassination plot by his chancellor, Hu Weiyong. The purge, begun with the chancellor's execution, went on for over a decade and rooted out any person with even the slightest connection - real or imagined - to Weiyong. Such was the effect of this reign of terror and the lack of enthusiasm amongst the educated scholar class to participate in the government, Hongwu was obliged to compel bureaucrats to accept official appointments and to ban resignations. Even the military did not escape, and the three top Ming generals were executed between 1393 and 1395 CE. By now in his mid-60s, it seems that the tighter Hongwu held on to power, the less grip he felt he had.

Death & Legacy

Hongwu had 26 sons, but his carefully groomed heir was to be his first son Zhu Biao, whom he had with Empress Ma. However, Biao's early death in 1392 CE would cause a reshuffling of the court hierarchy that had dire consequences. When Hongwu died in 1398 CE, he was succeeded by his second choice as heir, Biao's eldest son, Zhu Yunwen (aka Huidi), who took the reign name of Jianwen Emperor (r. 1398-1402 CE). This became the established method of the Ming dynasty to chose heirs to the throne; the eldest son of the Empress was first in line and, if he died before taking office, his eldest son would inherit. Jianwen would not last long as the second son of Hongwu, known as the Prince of Yan (and as Zhu Di), had ambitions of his own and did not take kindly at all to being overlooked. After a three-year civil war, this second son became emperor Chengzu, aka the Yongle Emperor (r. 1403-1424 CE) who would oversee an even greater flourishing of Ming China.