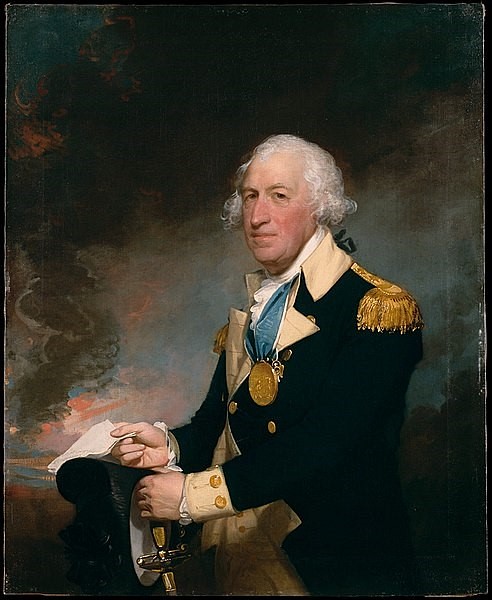

Horatio Gates (1727-1806) was an English-born general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Initially viewed as a hero for his stunning victory at the Battles of Saratoga, Gates' reputation was later tarnished by both his involvement in the Conway Cabal to replace George Washington as army commander, and his catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Camden.

Early Life & British Service

Horatio Gates was born on 26 July 1727 in Maldon, Essex County, England. He was likely the son of working-class parents Robert and Dorothea Gates; his mother, a housekeeper for the Duke of Bolton, was able to use her position to secure opportunities for her family that otherwise would have been out of reach. For instance, through her friendship with the waiting-maid of the Walpole family, Dorothea Gates managed to get future English writer and politician Horace Walpole (who was 11 years old at the time) to be the godfather of her son. In 1745, 18-year-old Horatio Gates was able to purchase a commission as an ensign in the British Army, largely thanks to the influence of the Duke of Bolton.

The young Ensign Gates has been described by biographers in unflattering terms; one characterized him as a "little ruddy-faced Englishman peering through his thick spectacles" and a "snob of the first water" (quoted in Boatner, 412). He first served with the 20th Regiment of Foot in Germany during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748) before volunteering to travel to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to serve under its governor, Edward Cornwallis; Cornwallis was not only an early mentor to Gates but also the uncle of Lord Charles Cornwallis, who would one day face Gates on the battlefield. Promoted to the rank of captain in the 45th Regiment of Foot, Gates saw action against the Mi'kmaq and Acadians in Canada. In 1754, he married Elizabeth Philips, daughter of a Nova Scotia councilman, with whom he would have one son, Robert (b. 1758).

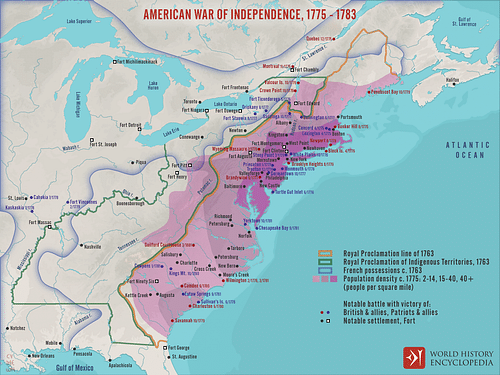

In 1755, as the French and Indian War (1754-1763) was escalating in North America, British General Edward Braddock was sent to lead an expedition to capture the French-held Fort Duquesne and thereby assert British control of the Ohio River Valley. Gates traveled to Fort Cumberland, Maryland, to join the expedition, where he would have met several other men who would one day also play key roles in the American Revolution including Daniel Morgan, Thomas Gage, Charles Lee, and, of course, Lt. Colonel George Washington of the Virginia militia. Braddock's Expedition set out on 29 May 1755 and made it to the Monongahela River a little over a month later, where it was ambushed by French troops and their Indigenous allies. General Braddock was killed in the ambush, and a large portion of his army became casualties including Gates, who was wounded. The survivors retreated to friendly territory.

After the Battle of the Monongahela, Gates was mainly relegated to positions of military administration, something at which he proved exceptionally talented. He served as chief-of-staff first to Brigadier General John Stanwix and then to Stanwix's replacement, Robert Monckton. In 1762, Gates accompanied Monckton in the capture of Martinique. Although Gates did not experience much combat during the expedition, he was nevertheless tasked with bringing news of the victory to England and was rewarded with a promotion to the rank of major. The war ended the following year and Gates returned to England, only to realize he had little future in the British Army; the limitations put on him by his social status meant that he could not advance much further in the military than he already had. Frustrated, Gates sold his major's commission in 1769 and, with assistance from his old army comrade George Washington, moved to Virginia with his family. Gates purchased Traveler's Rest, a Berkeley County plantation next door to Washington's younger brother, Samuel. As Gates began his new life as a Virginian planter, he also purchased several enslaved people to labor in his fields.

Early Revolutionary Career

Shortly after Gates moved to Virginia, tensions between the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain reached boiling point. After years of contention over issues such as 'taxation without representation' and the liberties of the American colonists, the first shots of the American Revolutionary War were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775). Despite his English blood, Gates soon became an outspoken supporter of the American cause; he likely spied a chance for advancement with the Americans that had been denied to him in Britain. In late May 1775, Gates rode to Mount Vernon to offer his services to Washington in person. Washington vouched for his old friend before Congress, helping to secure Gates' appointment as brigadier general and adjutant-general of the new Continental Army on 17 June.

Gates' military background made him invaluable to the fledgling United States. Gates, fellow British-born general Charles Lee, and Washington were some of the only Continental officers with any experience in the British Army. Gates spent the first months of the war putting his administrative skills to good use, creating the army's system of records and orders, and standardizing the regiments sent by the colonies. During the Siege of Boston (20 April 1775 to 17 March 1776) he served on Washington's council of war and urged caution whenever the commander-in-chief spoke in favor of reckless attacks on the British lines. After the Continentals recaptured Boston in March 1776, Gates was promoted to major general and sent to take command of the American troops at Fort Ticonderoga, where they were licking their wounds in the aftermath of the failed American invasion of Quebec.

Upon taking command at Ticonderoga, Gates frequently quarreled with his superior officer, Major General Philip Schuyler, who had command of the Northern Department of the Continental Army. The ambitious Gates wanted Schuyler's job and did everything he could to prove he was worthy of the position. He spent the summer of 1776 preparing for a British invasion of New York State, working with Benedict Arnold to enlarge the American fleet on Lake Champlain. When a British fleet finally set sail on the lake in early October, the American ships were ready; although the Americans were ultimately defeated in the ensuing Battle of Valcour Island (11 October 1776), the engagement was enough to postpone the impending British attack until the following year.

With the northern front temporarily secure, Gates marched south with New Jersey and Pennsylvania regiments reassigned to bolster Washington's main army. By now, New York City was under British control and Washington had been driven out of Manhattan and was currently retreating through New Jersey. Gates joined Washington's army on 20 December 1776, by which point he had apparently come to question the leadership of the commander-in-chief. Charles Lee, who had been captured by the British a week earlier, had sent Gates a letter in which he had confided his concerns that "a certain great man is damnably deficient" (Boatner, 413). Gates did not remain with the army for long; instead, he traveled to Philadelphia to petition Congress for greater support for the northern defenses. He was, therefore, not present when Washington won his stunning victories at the Battle of Trenton (26 December) and Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777), galvanizing renewed support for the American Revolution.

Hero of Saratoga

In early 1777, Gates returned to the Northern Department of the Continental Army to assume his role as second-in-command to General Schuyler. Shortly thereafter, British General John Burgoyne launched the long-anticipated invasion of New York and captured Fort Ticonderoga without much resistance on 6 July. Gates and his supporters in Congress managed to pin the blame for the loss on Schuyler, who was ousted from command on 4 August; at long last, the ambitious Gates was in command of an army of his own. As Burgoyne's force continued its slow southerly crawl along the Hudson River, Gates moved his army up from Albany. Perhaps on the advice of his subordinate, General Benedict Arnold, Gates opted to fortify Bemis Heights, a position beside the Hudson River about 9 miles (14 km) south of Saratoga, New York. Arnold and the Polish engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko set about fortifying the heights while Gates' army – which had blossomed to around 9,000 men and included Daniel Morgan's famous riflemen – dug in to await the coming of the British.

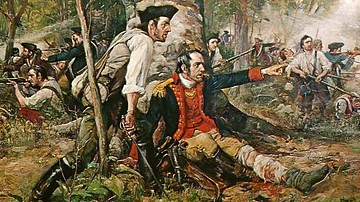

The fighting began on 19 September 1777 when Burgoyne attempted to outflank the American army by moving through the wooded area to the west of Bemis Heights. Arnold quickly realized what Burgoyne was doing and asked Gates for permission to lead a detachment of men into the woods to meet the British attack, where the American sharpshooters could use the dense foliage to their advantage. Gates, however, refused, preferring to wait and receive the British frontal assault. The two men argued for hours before Gates finally relented, allowing Arnold to take a small force consisting of Morgan's riflemen and Henry Dearborn's light infantry. Arnold led these men to meet the British advance at Freeman's Farm, sparking a fierce battle that lasted until dark, when the Americans withdrew back to their defenses, having successfully halted the British attack.

For the next several weeks, the American and British armies remained encamped within a mile from one another, as Burgoyne waited for reinforcements to arrive from Manhattan before renewing his attack. Time was against the British, however, as the American army atop Bemis Heights was growing every day; by early October, Gates' force had swollen to around 12,000 men. In the meantime, Gates had sent his report of the Battle at Freeman's Farm to Congress but had neglected to even mention Arnold's name. Outraged, Arnold confronted Gates, accusing him of cowering in his tent while the battle was being fought. The argument devolved into a heated shouting match, which ended with Gates stripping Arnold of his command. Arnold was still in the camp, however, when Burgoyne's second attack finally came on the morning of 7 October. Leaping into action, Arnold once again led the American counterattack, pushing the British back to their redoubts and receiving a leg wound in the process.

These two engagements, collectively known as the Battles of Saratoga, proved to be the greatest American victory of the war thus far. Burgoyne, who had been bested twice, realized that no help was coming from Manhattan; on 17 October 1777, he surrendered his entire army of 5,700 to Gates. The victory was widely celebrated throughout the United States and ultimately persuaded the Kingdom of France to enter the war on the American side, shifting the balance of power in the conflict. Although historians still debate Gates' exact contribution to the battles, he received most of the credit for the victory and was hailed as a war hero.

Conway Cabal

Gates' victory at Saratoga came at a time when Washington's main army was suffering defeat after defeat. Having failed to prevent the US capital of Philadelphia from falling into British hands, Washington had moved his army into winter quarters at Valley Forge, where it was now suffering from a severe shortage of food and clothing. Some Continental officers and members of Congress had become disillusioned with Washington's performance and plotted to replace him, in a loosely organized effort later known as the Conway Cabal. This so-called 'cabal' believed that the victorious Gates would be perfect as the next commander-in-chief. Gates, who had been criticizing Washington's performance since at least 1776, was clearly eyeing the job himself. Indeed, he had already snubbed Washington's authority by sending his report of Saratoga directly to Congress, rather than sending it first to the commander-in-chief, as was protocol.

To dilute Washington's authority, his enemies in Congress established a new Board of War and appointed Gates as its president, a move that turned Gates into Washington's superior. Gates attempted to further erode Washington's relevance by drawing up plans for an invasion of Canada; however, Gates' inability to adequately supply the soldiers that had gathered at Albany for the expedition undermined his long-standing reputation as a brilliant military administrator. To make matters worse for Gates, his aide-de-camp, James Wilkinson, drunkenly told one of Washington's loyal generals about scathing remarks that General Thomas Conway had made to Gates about Washington's leadership. Gates initially lashed out, accusing one of Washington's aides of having learned of the remarks by copying his private letters. But the damage had been done, leading many of Washington's supporters to view Gates as an opportunistic backstabber. By spring 1778, Washington had garnered renewed support in Congress for the army reformations he had overseen at Valley Forge, and the Conway Cabal against him fell apart. Hoping to salvage his relationship with Washington, Gates issued an apology and resigned from the Board of War in November.

Defeat at Camden

Although Gates' role in the Conway Cabal had soured his reputation amongst Washington's most loyal supporters, he was still regarded as a brilliant war hero by the American public. In May 1780, after American General Benjamin Lincoln was defeated at the Siege of Charleston, Gates' congressional supporters leveraged this popularity to get him appointed to the command of the Southern Department of the Continental Army. Gates arrived on 25 July to take charge of the 1,400 Continentals encamped at Deep River, North Carolina. He immediately ordered the army to march to Camden, South Carolina, where a British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis had established its headquarters. Gates' plan was to defeat Cornwallis and reconquer South Carolina.

His officers advised him against such a direct approach, arguing that the main road to Camden passed through war-ravaged territory and was interspersed with hostile Loyalist militia. Gates refused to listen and ordered his army onward. By 14 August 1780, he had reached Rugeley Mill, South Carolina, about 12 miles (19 km) from Camden; his army had been bolstered by Patriot militias and now numbered some 3,050 effectives. The next evening, Gates began his final push to Camden, but his confidence was shaken when Cornwallis' army suddenly appeared on the road. The two armies engaged on the morning of 16 August at the Battle of Camden, during which Gates' army was decisively defeated and practically annihilated. Gates himself fled the battle on horseback, abandoning his army and riding 170 miles (274 km) in three days before finally reaching the safety of Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Gates would later defend his conduct, arguing that he had only ridden ahead to scout out a safe place for his army to retreat to. Few people believed him, however, and Gates was widely accused of cowardice. He was removed from command in October and was replaced by General Nathanael Greene, one of Washington's most loyal officers. Gates returned to Virginia, his reputation in tatters, as some members of Congress called for a Board of Inquiry to look into Gates' conduct and gather evidence for a potential court martial. Although Gates' congressional allies prevented any such court martial from taking shape, the damage had been done, and Gates was never again trusted with a field command. His military career, which had begun in the British Army decades before and soared to great heights after Saratoga, had effectively ended in disgrace.

Later Life

On 22 October 1780, tragedy struck when Gates' only son Robert died after an illness. He spent the next year grieving and waiting for the accusations of cowardice against him to die down. Then, in late 1782, he rejoined Washington's staff at Newburgh, New York. By this point, many Continental officers were angry with Congress, which had failed to pay them the money it had promised. In 1783, many of these officers, including several of Gates' aides, joined together in the Newburgh Conspiracy, in which they plotted to take unspecified action against Congress. Gates himself supported the agitators, although the discontent was ultimately quelled after Washington made an emotional speech asking the officers to keep the faith and support Congress.

The war officially came to an end in September 1783 and Gates returned to Traveler's Rest the following year. His wife, Elizbeth, had died in the summer of 1783, leaving Gates to come back to an empty home. In 1784, he proposed marriage to Janet Livingston Montgomery, widow of General Richard Montgomery who had been killed at the Battle of Quebec, but she refused him. Instead, Gates would marry Mary Vallance in 1786. Like him, Vallance had been born in England before emigrating to the colonies in the early 1770s. She brought him a fortune of several hundred thousand dollars, much of which was later used to help Continental veterans. In 1790, Gates decided to sell his plantation. Perhaps at the urging of John Adams, he opted to emancipate his enslaved people as well. Contrary to popular belief, however, he did not free them immediately; rather, he stipulated in the sale contract that the five adult enslaved workers were to be emancipated after five years, while the eleven enslaved children on the plantation would only be freed once they reached the age of 28.

After selling his plantation, Gates moved to New York City, where he quickly integrated into high society. He became a supporter of the Democratic-Republican Party and vocally supported Thomas Jefferson's presidential campaign in 1800. That same year, Gates was elected to the New York State legislature and served a single one-year term before retiring from public life. He died on 10 April 1806 and was buried at Trinity Church Cemetery in Lower Manhattan.