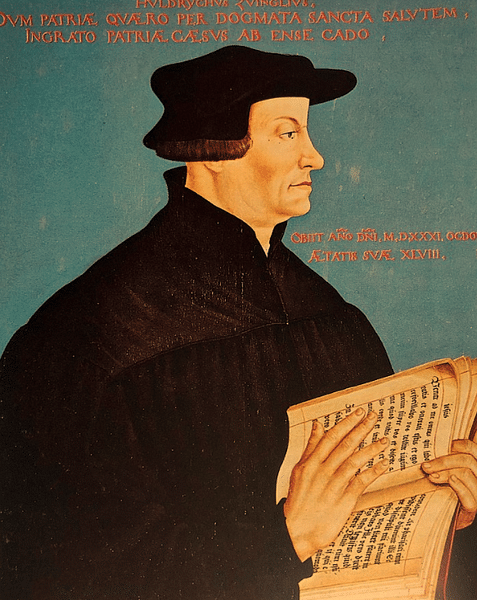

Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) was a Swiss priest who became the leader of the Protestant Reformation in the region at the same time Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) was active in Germany. Zwingli is known as the 'third man of the Reformation' following Luther and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) and the founder of the Reformed Church.

Like Luther, Zwingli did not initially set out to establish a new vision of Christianity but sought only to reform what he saw as errors and abuses in the policies of the Roman Catholic Church. As a Leutpriester ("people's priest") in Zürich, Switzerland, he began his efforts by reading directly from the New Testament and interpreting it in the vernacular rather than following the Church's liturgy in Latin. He then refuted the tradition of fasting during Lent and finally the Church's practice of the Eucharist and Mass. Like Luther, he was able to popularize his views owing to the support of powerful men on the city council and his use of the printing press.

Having established the Reformed Church in Zürich, he suppressed other efforts at further reform in the city, notably persecuting the Anabaptists who disagreed with his views on infant baptism. His efforts at forcible conversion of the Swiss cantons (provinces or counties) led to the First Kappel War of 1529 – averted by compromise – and the Second Kappel War of 1531 during which he was killed. He was succeeded as leader of the Swiss Reformed Movement by Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575) who further developed his vision. He is recognized as the Father of the Swiss Reformation and one of the most important activists of the Protestant Reformation.

Early Life, Education,& Service

Zwingli was born in the Toggenburg Valley, Switzerland, in the village of Wildhaus on 1 January 1484 to an affluent farmer and magistrate (whom he was named after) and Margaret (nee Meili) Zwingli whose brother, Bartholmaus, was a priest and dean of the school at Wesen. Zwingli was the third of eleven children and, showing early intellectual promise, was tutored by his uncle, who brought him to Wesen and then encouraged him to continue his education at Basel and Bern. He was already an accomplished musician by 1496 when he was twelve years old and well-read in the classics. He graduated from the University of Basel with his Master of Arts degree in 1506 when he was 22, was ordained a priest at Constance, and returned home to celebrate his first Mass in September of that same year.

At this time, Switzerland was a confederation of 13 cantons each operating nearly independently of the others. Cantons themselves remained neutral during the various conflicts of the states around them and, though technically part of the Holy Roman Empire, retained their autonomy. Each canton was free, however, to supply mercenaries to whomever they pleased and did so regularly. Zwingli was sent from his hometown to take over the position of the village priest in Glarus and volunteered to accompany the mercenaries of Glarus on campaign as their chaplain in 1513.

Experiencing war first-hand, Zwingli recognized armed conflict was antithetical to the Christian vision of peace and forgiveness of one's enemies. When the Swiss were defeated by the French army at the Battle of Marignano in September 1515, Zwingli returned to Glarus, but as he had formerly supported the mercenary system, specifically mercenaries supplied to the Papal States, the people of Glarus – who now supported the French cause against the Papal States – rejected him, and he moved to Einsiedeln in Schwyz canton.

It was in Einsiedeln that he first read the works of Desiderius Erasmus (l. 1466-1536), the great Dutch philosopher, theologian, and humanist. He had met Erasmus at Basel in 1514 but was now more deeply influenced by his philosophy and may have assisted in Erasmus' translation of the New Testament in 1516. Erasmus never joined the Reformation movement but advocated reform from within the Church, and his arguments deeply affected Zwingli, especially his criticisms of the policy of indulgences. By 1518, Zwingli had also read Martin Luther's 95 Theses denouncing indulgences – writs people paid for to lessen their time, or a loved one's, in purgatory – and had written pieces critical of the Church. These were presented as satires, however, and were regarded as so cleverly composed they were understood as entertainment, and instead of being censured, he was appointed the people's priest at the Grossmünster (Great Minster/Great Church) in Zürich.

Zürich & the Sausage Episode

Zwingli's position as people's priest was technically subordinate to the canons (magistrates) of Zürich, but as the leading ecclesiastic of the Great Church of the city, he assumed a position of power among his congregation. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch comments:

Straight away on his arrival in 1519, he announced that he would begin systematically preaching through the Gospel of Matthew, brutally ignoring the complicated liturgical cycle of readings from the Bible which the Church laid down. The Book of Acts followed, taking him from the life of Christ to the subsequent founding of the first Christian congregations, and his preaching no doubt intensified for him the sense of how different the Church seemed to be in his own time. (138)

Zwingli not only read the Bible to the people but also interpreted and commented on the passages and encouraged the spirit of reform in Zürich. MacCulloch notes how "through 1520, Zwingli's close relationship with his enthusiastic congregation began to fuse with his own convictions of the need for church reform" (138). His relationship with the people of Zürich had been further strengthened in 1519 when the plague struck the city killing one out of every four. Most of the clergy fled, but Zwingli remained, caring for the sick, and nearly died when he caught the plague himself.

In 1521, in spite of opposition from more conservative canons, he was appointed a canon and made a citizen of Zürich. This same year, news of Martin Luther's refusal to recant at the Diet of Worms reached Zürich as well as the Edict of Worms condemning him. The Swiss authorities refused to publish the Edict of Worms but were reluctant to endorse reformation outright. Zwingli forced their hand in 1522 after an event often referred to as the Sausage Episode or Affair of the Sausage. MacCulloch comments:

Early in 1522, on the first Sunday in the penitential season of Lent, a Zürich printer, Christoph Froschauer, sat down with a suspiciously biblical tally of twelve friends or thereabouts, cut up two sausages, and distributed them to his guests. Zwingli sat out the sausage, alone among the company, but when the row became public (as was surely intended), he first devoted one of his Sunday sermons to showing why it was unnecessary to obey the traditional Church's order not to eat meat in Lent, and then published what he had preached…Zwingli's point in his sermon was that there was no Lenten commandment in the Gospel; it was a human command introduced by the Church. (139)

The Zürich city council at first intended to prosecute Froschauer until Zwingli made a case against Lenten fasting in his sermon, published as Regarding the Choice and Freedom of Foods. The bishop denounced Zwingli, and the other Swiss cantons agreed that Zwingli's preaching should be suppressed along with any other new views on Christian policy and practice.

First & Second Disputations

The Zürich council, however, believed both sides should be heard and the matter decided reasonably through disputation and debate. They arranged for the First Disputation to take place in January 1523, inviting the bishop who sent a delegation headed by the vicar general Johannes Fabri. Fabri anticipated a private debate in closed quarters while Zwingli prepared for a public event. Over 600 people arrived and listened to Zwingli's 67 Articles articulating his vision. Fabri was prohibited from discussing theological matters in front of the masses and so could only respond by asserting the authority of the Church without any arguments for support. Zwingli won and was ordered by the council to continue to preach according to scripture.

Zwingli had recommended a fellow priest, Leo Judd (l. 1482-1542) as pastor of Saint Peter's Church in Zürich, and Judd supported Zwingli's views, joining him in the Second Disputation in October of 1523. Judd had denounced the presence of religious statuary and icons in churches and called for their removal, prompting Zwingli's followers to destroy the statues of saints, stained-glass windows depicting biblical scenes, and any other iconography as idolatrous. Zwingli, meanwhile, had rejected the Mass and the understanding of the Eucharist as a miracle of transubstantiation (whereby the bread and wine became Jesus Christ's body and blood) arguing that it was instead a commemorative rite.

The Second Disputation concluded without fully resolving the issues but allowing individual churches to decide on the removal of statuary. Zwingli compromised and allowed for a gradual move away from the Mass and the veneration of icons, but his ideas had already been embraced by the people who refused to observe traditional Christmas rites, and in 1524, the rituals surrounding Easter were abandoned.

Zwingli & Authority

Zwingli maintained there were only two sacraments – baptism and the Eucharist – both to be understood as gestures of membership in the Christian faith but has no other attributes. He also denounced clerical celibacy as unbiblical and pointed out that many from the clergy lived with women without the benefit of marriage and so insistence on celibacy encouraged hypocrisy and deceit. Zwingli himself had lived with the widow Anna Reinhart in secret and married her in 1524, a marriage that would produce four children (Regula, William, Huldrych, and Anna), and encouraged others to do the same.

He maintained that the Bible was the only authority, not only in ecclesiastical but also secular spheres, and citing Erasmus, he claimed that a perfect state would be a humanist-Christian entity under which all would live in peace as early Christianity was depicted in the Book of Acts. His claims, and the movement he set in progress, challenged the existing order on every level and introduced a new model for society, which the people of Zürich struggled to reconcile with their traditions.

Zwingli encouraged these changes, arguing that scripture alone provided the laws everyone should live by, and eventually translating the Bible, with Judd, to create the Zürich Bible (also known as the Froschauer Bible) by 1531. He was supported by the city council, and his ideas spread, not only through his spoken sermons but their printed versions in the vernacular. His call to disband mendicant orders and convert monasteries and convents into hospitals and orphanages was approved by the council and acted on with the support of Katharina von Zimmern (l. 1478-1547), abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey in Zürich (and a former friend of Zwingli's) who handed it over to the city in 1524.

Persecution of Anabaptists

Zwingli's rejection of any central religious authority outside of scripture, however, encouraged some of his followers to take his claims to their natural conclusion. If anyone's Christian vision could be valid, if they could support it from scripture, then anyone else's could be challenged, including Zwingli's. One of Zwingli's most ardent supporters was Conrad Grebel (l. c. 1498-1526) who, along with Felix Manz, broke with Zwingli after the Second Disputation, claiming he had compromised himself on the issues and sided with the establishment against the truth of scripture.

Grebel especially took exception to Zwingli's stand on infant baptism, claiming it was unbiblical since any mention of baptism in the Bible concerned a consenting adult who submitted to the ritual for the remission of sins. Since an infant could not consent, Grebel argued, the rite must be rejected as a man-made construct, not of God. Grebel and his followers were called Anabaptists (re-baptizers) by their opponents, a pejorative term intended to highlight their insistence on performing a ritual already completed shortly after one's birth. The city council supported Zwingli's approval of infant baptism and, in 1525, ordered all people in Zürich to have their infants baptized or leave the city.

In 1526, the council posted its mandate that adult baptism was against the law, and anyone caught engaging in the practice would be put to death. Felix Manz refused to comply, continuing adult baptisms at his house and around the city until he was arrested and executed by drowning in 1527. Three other Anabaptists were also drowned in the Limmat River shortly afterwards, and the rest left the city. Grebel had already left Zürich in 1525 but continued his Anabaptist evangelism until he died, probably of disease, in 1526. Zwingli had not consented to the mandate but had rebuked the Anabaptists as irresponsible radicals. and there is no evidence he objected to the mandate or the executions.

Baden Disputation & Marburg Colloquy

As Zwingli's power in Zürich grew, his religious views became more and more entwined with civic matters, and he was convinced that a Christian state operating solely on scripture was not only ideal but a practical possibility. A united Switzerland, he felt, based on Reformed Christianity, was as close at hand as the conversion of the other cantons. Five of the cantons rejected Zwingli's plans and called on the Church to resolve the matter. In May 1526, all the cantons met at Baden, where the Church was represented by Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543) who had debated Martin Luther, while Zwingli,s side was represented by his friend and theologian Johannes Oecolampadius (l. 1482-1531). Throughout the disputation, Zwingli was constantly kept informed of the proceedings and sent notes to Oecolampadius as well as printing pamphlets refuting the Church's arguments.

The Baden Disputation ended with all but four of the 13 cantons voting to suppress Zwingli's teachings. Basel, Bern, Schaffhausen, and Zürich, supported him, however, and the Reformed Movement, already well established in Zürich, was founded in Bern in 1528. When a Reformed priest was arrested and executed in the Catholic canton of Schwyz, Zwingli saw no other way toward a united Reformed Switzerland than war. Rejecting his earlier pacifism, as well as Erasmus' claim that reasonable men could resolve differences peacefully, he mobilized Zürich for war, but a delegation from Bern negotiated a truce before armed conflict began.

Zwingli was now at odds not only with former supporters (the Anabaptists) and the Catholic cantons but also with Luther in Germany who had denounced his views on the Eucharist in 1527. The German noble Philip of Hesse (l. 1504-1567), a staunch supporter of Luther, brought the two men together at Marburg in 1529 to iron out their differences in the hopes of creating a united Protestant front against the Catholics. Zwingli enthusiastically accepted the invitation while Luther, who dismissed Zwingli as a dangerous radical, was forced by Philip to attend. The two were able to agree on 14 of the 15 points under consideration but could not agree on the last – the Eucharist. To Luther, Christ was literally present during the ritual, while for Zwingli, the rite was simply a remembrance of Christ's sacrifice.

Zwingli is said to have been visibly upset by Luther's dismissive use of him throughout the Marburg Colloquy while Luther never seemed to care what Zwingli thought of him. A year later, at the Diet of Augsburg, Luther's friend Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) presented his Augsburg Confession mostly to resolve differences between Catholics and Lutherans but certainly with Zwingli in mind in an attempt at reconciliation. Zwingli's own Confession at the conference alienated both Catholics and Lutherans in its extremism. When Luther later heard of Zwingli's death, he pronounced it the just work of God, enacted to prevent Zwingli from destroying the movement through radical excess.

Conclusion

Continuing his vision of a united Reformed Switzerland, Zwingli advocated an attack on the Catholic cantons in early 1531 but, lacking support from the other Reformed cantons, compromised with a blockade, which was supposed to starve the Catholics into submission. Food reached the cantons by other routes, however, rendering the blockade pointless, and it was withdrawn. Zwingli continued to argue for armed conflict in converting what he saw as the stubborn Catholic cantons who continued to adhere to ungodly views.

In October 1531, the Catholic cantons declared war on Zürich and moved quickly against the city. Zürich was caught off guard, mobilizing slowly and lacking cohesion and strong leadership, but marched to meet an opponent whose numbers were twice their own near Kappel. The Second Kappel War consisted of a single battle concluded in under an hour with a Catholic victory. 500 of Zürich's soldiers fell, including Zwingli.

After his death, he was denounced for the Kappel Wars and the movement he had led was harshly criticized. Judd, who was closely associated with him, was ostracized, and eventually came to a more moderate position while Heinrich Bullinger, who had already shifted to a more moderate stance, succeeded Zwingli as leader of the Reformed Church. In time, however, Zwingli's revolutionary concepts prior to the Kappel Wars came to be recognized as necessary in establishing the new vision which would be more completely developed by Calvin in the latter stages of the Swiss Reformation. In the present day, Zwingli is understood as one of the most important activists of the Protestant Reformation who, like Luther and Calvin, challenged the old order to establish a new vision of Christianity.