The Hundred Days refers to the second reign of French Emperor Napoleon I, who unexpectedly returned from exile to reclaim the French throne. It encompasses Napoleon's triumphant return to Paris on 20 March 1815, his climactic defeat at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June, and the restoration of King Louis XVIII on 8 July, a period of 110 days.

After his initial defeat in the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814), Napoleon was forced to abdicate the imperial throne and was exiled to the island of Elba. He remained there for nine months, but political unrest in France and disagreement between the great powers of Europe induced him to make a bid for his old throne. He landed in southern France on 1 March 1815 and arrived in Paris only 20 days later, beginning his second reign. The Allies immediately declared him an outlaw and pledged to dethrone him once again; Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and abdicated for a second time four days later. The Bourbons were restored to the French throne, and Napoleon was once again exiled, this time to the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where he would die six years later. The Hundred Days, therefore, marks the final stage of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

Abdication

On 11 April 1814, French Emperor Napoleon I signed an act of unconditional abdication at the palace of Fontainebleau. It was a bitter pill to swallow since less than two years earlier, he had been the master of continental Europe, ruler of a vast empire that stretched from Iberia to Poland. However, after the catastrophic failure of Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812, his enemies – including Austria, Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Sweden – banded against him in the War of the Sixth Coalition. After dealing Napoleon a crushing defeat at the Battle of Leipzig (16-19 October 1813), the Coalition armies pushed into France, determined to depose the French emperor. Napoleon initially showed resilience, winning a series of victories on French soil in his impressive Six Days Campaign (10-15 February 1814), but the overwhelming number of Coalition troops, as well as the apathetic attitude of a war-weary French populace, meant that Napoleon's defeat was only a matter of time. Paris fell to the Coalition on 30-31 March 1814, and a provisional French government was set up to negotiate peace.

Even then, Napoleon was determined to fight on and was convinced that his soldiers would follow him to the bitter end, but his marshals, determined to prevent civil war and more bloodshed, told their emperor that the army would march no further. "The army will obey me!" said Napoleon to Marshal Michel Ney, who stood his ground, replying that "the army will obey its chiefs" (Chandler, 1001). Having been abandoned by France and by his marshals, Napoleon had no option left but to abdicate, which he agreed to do on 6 April. A few days later, he attempted suicide by swallowing a capsule of poison, but the poison's potency had weakened with age, and it did not work. On 11 April, Napoleon signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau, in which he agreed to abdicate the French throne. In return, he would be granted sovereignty over the Mediterranean island of Elba, off the coast of Italy, as well as a pension of 2.5 million francs per year. He would be allowed to retain the title of 'emperor' and could keep a skeleton force of 600 Imperial Guardsmen to defend the island against the Barbary pirates of North Africa.

On 20 April, Napoleon left Fontainebleau after a dramatic scene in which he said farewell to his faithful Old Guard in the palace courtyard. He was taken to Elba aboard the British vessel HMS Undaunted, arriving at the island's main harbor of Portoferraio on 3 May. That same day, King Louis XVIII of France, brother of the king who had been guillotined during the French Revolution, arrived in Paris to claim his throne after more than two decades in exile. A few months later, the victorious powers of the Sixth Coalition convened the Congress of Vienna to redefine the balance of power in Europe and redraw the map of a post-Napoleonic world. To all contemporary observers, the great Napoleonic epic appeared to be over; few could have guessed that one final act was still to be played out.

Exile to Elba

Napoleon remained sequestered in Elba for nine months, during which time he kept himself busy. The day after landing, he inspected Portoferraio's defenses and iron mines; over the coming months, he dedicated his energy to building a hospital, planting vineyards, paving roads, and building bridges. He reorganized Elba's defenses, gave money to the poorest of the island's inhabitants, and built a fountain on the roadside of Poggio, which still works today (Roberts, 723). To his British observers, it seemed that Napoleon had come to grips with his new reality and had become content with his tiny new kingdom. In truth, Napoleon was eagerly reading any news that arrived from the continent, looking for an opportunity to reclaim the French throne. As luck would have it, a chance would soon present itself.

Napoleon's decision to return to France was informed by two major factors. The first was the political unrest in France, which had arisen in response to the Bourbon Restoration. King Louis XVIII was certainly no tyrant; indeed, he had granted the Charter of 1814, a liberal constitution that retained the French Revolution's social changes and preserved the Napoleonic code. However, Louis XVIII was accompanied by many Ancien Régime nobles who had fled France during the Revolution and were less interested in compromise. Known as 'Ultras' for their radicalism, these nobles sought a return of their former lands and power. They antagonized French republicans and Bonapartists alike by hosting ceremonies honoring those who had fought against the Revolution. The fact that Louis XVIII appointed many 'Ultras' to high positions caused many to fear that feudal and church taxes would soon be reimplemented. Moreover, Louis XVIII won no friends when he replaced the French tricolor with the white flag of the Bourbons, and he alienated the army by dismissing thousands of troops and putting officers on half-pay. Already, many were looking back on the Napoleonic regime with nostalgia.

The second factor that influenced Napoleon's return was the deteriorating relations between the great powers of Europe. These powers had been united by a common desire to defeat Napoleon; now that this had been accomplished, however, old rivalries returned to the forefront. At the Congress of Vienna, delegates quarreled over the futures of Poland and Germany; Russia wanted to create a Polish puppet state, while Prussia felt entitled to almost all the territory belonging to the Kingdom of Saxony. Attempts by Austrian and British delegates to prevent this almost erupted into war. Though compromises were eventually reached, tensions between the great powers had yet to fully simmer.

These two developments left Napoleon hopeful. With France disillusioned with the Bourbons, and the allies at one another's throats, Napoleon gambled that his return would be welcomed in France and ignored by the European powers. On 26 February 1815, he left Elba aboard the vessel L'Inconstant with his staff and around 1,000 soldiers and set sail for France. On 1 March, they landed on the southern French coast near Cannes; as they began unloading, they were approached by a large crowd that marveled at the sight of the returned emperor. As Napoleon would later recall in his memoirs:

Among them was a mayor, who, seeing how few we were, said to me: 'We were just beginning to be quiet and happy; now you are going to stir us all up again' (Roberts, 731).

Flight of the Eagle

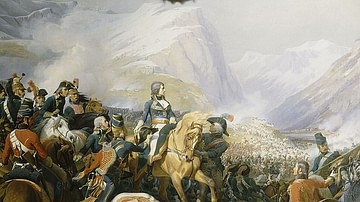

From Cannes, Napoleon issued a proclamation in which he promised that "the eagle will fly from belfry to belfry until it reaches the towers of Notre Dame" (Mikaberidze, 604). This began what is popularly known as the Flight of the Eagle, one of history's most dramatic episodes. From Cannes, Napoleon carefully made his way through the conservative Provence region, avoiding the city of Aix and instead moving through the Alps, traveling mainly on foot. On 5 March, he began to travel through sympathetic regions like Dauphine, where he was greeted by jubilant crowds. The route taken by Napoleon is today known as the Route Napoléon and has become a popular tourist destination and cycling path.

Near the town of Laffrey, Napoleon encountered the first obstacle when he ran into a battalion of the 5th Line, which had been sent to arrest him. According to Bonapartist legend, Napoleon ordered his grenadiers to lower their weapons before stepping toward the soldiers of the 5th, whose own muskets were leveled at his chest. "Soldiers," cried Napoleon, "I am your emperor. Do you not recognize me? If there is one among you who would kill his general, here I am!" (ibid). A royalist officer gave the command to fire, but not a shot rang out; instead, the soldiers rushed forward and embraced Napoleon with shouts of "Vive l'empereur!" Whether or not this story was embellished, it is true that Napoleon was joined by defecting French troops wherever he went. On 10 March, Marshal Ney left Paris with 6,000 men, promising Louis XVIII that he would return with Napoleon in "an iron cage"; less than a week later, Louis XVIII received word that Ney had joined Napoleon and had publicly announced that "the cause of the Bourbons is lost forever!" (ibid).

Napoleon's progress was rapid. On 7 March, he entered Grenoble after a crowd of fanatic citizens tore down the city gates and presented him with the pieces. Three days later, he was in Lyon, writing imperial decrees. On 20 March, he finally entered Paris, where he was practically carried by ecstatic mobs to the Tuileries Palace; Louis XVIII had vacated the city only hours before and fled to Belgium. In less than a month, Napoleon had reclaimed his empire without firing a shot. All that was left was to keep it.

Constitutional Reform

Within hours of Napoleon's return, it was left to his former servants to decide where their loyalties lay. Ten of his former marshals declared allegiance to Napoleon, though only three – Ney, Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and Emmanuel de Grouchy – would command troops during the Waterloo campaign. Louis-Nicolas Davout, arguably Napoleon's most talented marshal, was relegated to a desk job as minister of war, a decision that many future Bonapartist sympathizers have lamented as a waste of his talents. Napoleon was also joined by three of his brothers, Joseph, Lucien, and Jerôme, though his brother Louis and stepson Eugène de Beauharnais stayed away. His reconstituted government was not short on talented ministers and included Armand de Caulaincourt as foreign minister, Joseph Fouché as minister of police, and Lazare Carnot as minister of the interior.

Yet Napoleon understood that public opinion was fickle, that he could lose his throne just as easily as he had regained it. Realizing his new government could not exist in the way it had before, he presented himself as a changed man who no longer cared for conquest or autocratic rule. To prove this, he invited longtime critic Benjamin Constant to draw up a new constitution, which would include a bicameral parliament that would share power with the emperor, based on the British model. He also ended censorship and abolished the slave trade entirely. Napoleon repeatedly denied that he had any imperial ambitions, promising that "henceforth, the happiness and consolidation of the French Empire will be the objects of my thoughts" and that "from now on it will be more pleasant to know no other rivalry than that of the benefits of peace" (Mikaberidze, 605; Roberts, 746).

Of course, many were skeptical of Napoleon's supposed reformation; after all, this was the same man who had once remarked that "a deliberative body is a fearful thing to deal with" (Mikaberidze, 606). Indeed, Napoleon had to be dissuaded by his advisors from stopping the election of one of his opponents to the presidency of the new Chamber of Representatives on 3 June. Many in France continued to resist Napoleon's rule; the local notables of Flanders, Artois, Normandy, Languedoc, and Provence refused to rally to Napoleon's cause, while the regions of Brittany and the Vendée erupted into armed revolt.

The Allied powers, meanwhile, did not believe that Napoleon had put aside his imperial ambitions. On the morning of 7 March, as soon as he received word that Napoleon had escaped Elba, Austrian foreign minister Klemens von Metternich informed the monarchs of the great powers, who were still gathered at Vienna. Within hours, the Allied leaders agreed to begin mobilizing their forces. On 25 March, the Allies officially put aside their differences and formed the Seventh Coalition, declaring war not on France but on Napoleon himself; the Allies branded Napoleon an outlaw and pledged not to lay down their arms until he was defeated for good.

Waterloo Campaign

The Allies decided to threaten northwestern France by invading Belgium; this would be carried out by a Prussian army of 120,000 men led by Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, and an Anglo-allied army of 100,000 troops led by Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. A 200,000-man Austrian army would simultaneously take up position on the Upper Rhine, supported by 150,000 Russian troops on the Middle Rhine. Napoleon, meanwhile, was able to gather an army of 250,000 men by June. The only nation to side with France was Naples, whose king, Joachim Murat, saw an alliance with France as the only way to save his throne. However, Murat was defeated by an Austrian army at the Battle of Tolentino (2-3 May 1815) and deposed; he would later be executed on 13 October after trying to instigate a Neapolitan insurrection.

On 14 June, Napoleon launched an offensive into Belgium. His Army of the North was divided into two wings; the left flank was commanded by Marshal Ney, the right was led by Marshal Grouchy, and Napoleon himself commanded the Imperial Guard in the reserve. Napoleon's offensive caught the Allies by surprise; on 15 June, Wellington was in Brussels, attending the Duchess of Richmond's ball. When informed of the enemy's rapid advance, he exclaimed, "Napoleon has humbugged me, by God!" (Roberts, 751). Indeed, at that moment, Napoleon was advancing toward Blücher's army at Ligny, hoping to defeat each Allied army piecemeal. On 16 June, Napoleon attacked and defeated Blücher at the Battle of Ligny, inflicting around 17,000 Prussian casualties and losing 11,000. The same day, Ney engaged Wellington's army at the Battle of Quatre Bras; although Ney prevented Wellington from marching to Blücher's aid, he failed to decisively defeat Wellington's army.

At noon on 17 June, Napoleon sent Grouchy's 33,000 men to pursue the Prussians before joining Ney at Quatre Bras. By this point, Wellington had learned of Blücher's defeat at Ligny and had retreated to take up a defensive position on the ridge of Mont-Saint-Jean, only a few miles south of his headquarters at Waterloo. Napoleon pursued, his troops marching with difficulty through the driving rain. He ignored his officers' warnings to not underestimate Wellington; Napoleon dismissed the British duke as a "bad general" and the English soldiers as "bad troops", quipping that "this affair is nothing more serious than eating one's breakfast" (Mikaberidze, 610). Napoleon launched his attack just after 11 a.m. on 18 June, ordering a series of frontal assaults on the Allied line. Although Wellington's troops held their ground, the situation had become perilous by the late afternoon, when the French captured La Haye Sainte and almost broke through the Allied center.

It was at this moment that Blücher arrived with 50,000 men, having left one corps behind to pin down Grouchy at the Battle of Wavre. In a final gambit to regain control of the battle, Napoleon committed his Imperial Guard, sending them up the ridge against the Allied line. But not even the famed Guard could break through Wellington's line, and before long, the French army had been routed. Between 25,000 and 31,000 French soldiers had been killed or wounded, compared to around 26,000 Allied casualties. Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo sealed the fate of the French Empire.

Exile to St. Helena

Napoleon returned to Paris on 21 June and abdicated for a second time the following day in favor of his son, the four-year-old Napoleon II. On 25 June, Napoleon left Paris and fled to Rochefort, where he intended to seek passage to the United States. However, when he arrived at Rochefort, he found that it was being blockaded by Royal Navy vessels. On 7 July, the Coalition forces entered Paris, and Louis XVIII was restored to his throne the following day. Marshal Ney was arrested on 3 August for his role in Napoleon's return and was executed by firing squad in December 1815.

Napoleon, meanwhile, surrendered to Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland of HMS Bellerophon on 15 July 1815. His request for asylum in London was denied; the Allies ruled on 2 August that Napoleon was a prisoner of war and should be confined to a place from which he could not escape. To this end, he was exiled to St. Helena, a lonely island in the South Atlantic about 2500 km (more than 1,500 miles) from the nearest coastline. Napoleon would spend the rest of his life on St. Helena, closely watched by his British captors until his death on 5 May 1821.