The Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) was an intermittent conflict between England and France lasting 116 years. It began principally because King Edward III (r. 1327-1377) and Philip VI (r. 1328-1350) escalated a dispute over feudal rights in Gascony to a battle for the French Crown. The French eventually won and gained control of all of France except Calais.

At first, the English won great victories at the battles of Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356) but then Charles V of France (r. 1364-1380) steadily regained much of the lands lost since the start of the war. After a period of peace when Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399) married the daughter of Charles VI of France (r. 1380-1422), the war exploded into action again with the Battle of Agincourt (1415), won by Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422). Henry was nominated the heir to the French throne but his early death and the ineffectual rule of Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71) resulted in Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461) retaking the initiative. With help from such figures as Joan of Arc (1412-1431), the French won crucial battles at Formigny (1450) and Castillon (1453) to bring final victory.

War & Peace

The Hundred Years' War was a conflict between the monarchs of France and England. Starting in 1337 and not finally ended until 1453, the war lasted for 116 years, albeit not with continuous fighting but also long periods of peace included. The name we use today for the war was only coined in the 19th century. The Hundred Years' War is traditionally divided into three phases for the purposes of study and to reflect the important periods of peace between the two countries:

- The Edwardian War (1337-1360) after Edward III of England

- The Caroline War (1369-1389) after Charles V of France.

- The Lancastrian War (1415-1453) after the royal house of England, the Lancasters.

Causes of the War

The causes of the Hundred Years' War are as complex as the conflict itself would later become. In addition, motivations changed as various monarchs came and went. The principal causes may be listed as:

- The seizure of English-held Gascony (Aquitaine, south-west France) by Philip VI of France.

- The claim by the English king Edward III to be the rightful king of France through his mother.

- The expedition of Edward III to take by force territories in France, protect international trade and win booty and estates for his nobles.

- The ambition of Charles V of France to remove the English from France's feudal territories.

- The descent into madness of Charles VI of France and the debilitating infighting amongst the French nobility.

- The ambition of Henry V of England to legitimise his reign in England and make himself the king of France through conquest.

- The determination of the Dauphin, future King Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461), to regain his birthright and unify all of France.

The Edwardian War (1337-1360)

Edward III was able to make a strong claim to the French crown via his mother Isabella. Whether or not this claim was a serious one or merely an excuse for invading France is debatable. Certainly, on paper Edward did have a point. The current French king was Philip VI of France who had succeeded his cousin Charles IV of France (r. 1322-1328) even if, when Charles had died, it was Edward who was his closest male relative, being Charles' nephew and the eldest surviving grandson of Philip IV of France (r. 1285-1314). The English king had not pressed his claim at the time because he was a minor, and the French nobility, discounting the legitimacy of inheritance through the female line, had naturally preferred a Frenchman as their ruler. However, by the mid-1330s Edward changed his strategy, perhaps irked by the technicality that, as the Duke of Gascony, the English king was actually a vassal of the French king according to the rules of medieval feudalism. Gascony was a useful trade partner of England's, wool and grain being exported and wine imported. When the French king confiscated Gascony to the French Crown in 1337 and raided the south coast of England the year after - an attack which included the destruction of Southampton, Edward was presented with the perfect excuse to start a war.

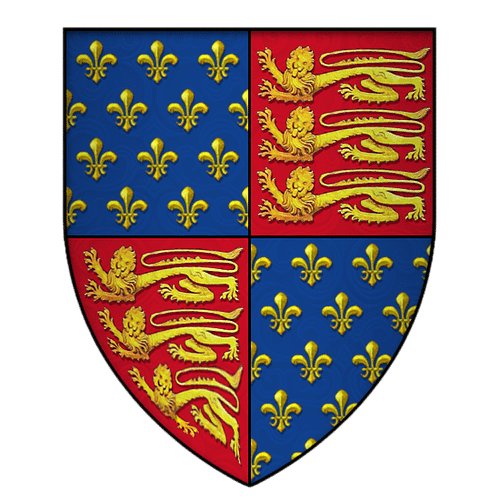

Edward got the ball rolling by declaring himself King of France in a ceremony in Ghent in January 1340. In addition, the king showed off his newly quartered coat of arms - the three lions of the Plantagenets - to now include the golden fleur-de-lis of France. The Low Countries were important trading partners with England while other allies included rivals to Philip VI such as Charles II, King of Navarre (r. 1349-1387) and the Gascon counts of Armagnac.

One of the first major actions of the war was in June 1340 when a French invasion fleet was sunk by an English fleet at Sluys in the Scheldt estuary (Low Countries). This was followed up in 1345 with the capture of Gascony and invasion of Normandy where the strategy of chevauchées was employed, that is striking terror into local populations by burning crops, raiding stocks, and permitting general looting in the hope of drawing the French king into open battle. The strategy worked and the French army, unable to find a response to the combination of English archers and knights fighting on foot, suffered a heavy defeat at the Battle of Crécy in August 1346. Philip was far from beaten, though, and cleverly called on his Scottish allies to invade northern England in the hope that this would force Edward to withdraw from France. David II of Scotland (r. 1329-1371) duly obliged and invaded England in October 1346 but was defeated by an English army at the Battle of Neville's Cross (17 October 1346). As an extra bonus, King David was captured and only released in 1357 as part of the Treaty of Berwick, where the Scots paid a ransom and a 10-year truce was agreed between the two countries.

In 1347 Calais was captured but the arrival of the Black Death plague in Europe interrupted the hostilities. The next major victory was another English one, once again against a much larger French army, this time at the Battle of Poitiers in September 1356. Here the English army was led by Edward's able son, Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376). The defeated King John II of France (r. 1350-1364) was captured at Poitiers and was detained for four years. The 1360 Treaty of Brétigny was then signed between England and France which recognised Edward's claim to 25% of France (mostly in the north and south-west) in return for Edward renouncing his claim to the French crown.

The Caroline War (1369-1389)

The Peace of Brétigny ended in 1369 when the new French king, Charles V of France aka Charles the Wise (r. 1364-1380), began to grab back in earnest what his predecessors had lost. Charles did this by avoiding open battle, concentrating on harassment and relying on the safety of his castles when required. Charles also had a superior navy to the English and so was able to make frequent raids on the south coast of England. Most of Aquitaine was grabbed in 1372, an English fleet was defeated off La Rochelle in the same year and, by 1375, the only lands left in France belonging to the English Crown were Calais and a slice of Gascony.

In 1389 a truce was declared once again and relations further improved when, on 12 March 1396, Richard II of England married Isabella of France, the daughter of Charles VI of France. The union cemented a two-decade truce between the two countries. Under the next king, Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413), the Crown was rather too preoccupied with rebellions in England and Wales to do very much in France.

The Lancastrian War (1415-1453)

Henry V played the next significant move in this game of thrones as he was even more ambitious than Edward III had been. Not only did he want to plunder French territory but to permanently take it over and form an empire. For the king, success in war was also a useful tool in legitimising his reign, inheriting as he had the crown from his father Henry IV who had usurped the throne by murdering Richard II. Henry V was greatly helped by the descent into madness of Charles VI of France and the consequent split in the French nobility between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians over who might control the king and France.

Henry invaded Normandy, captured the important port of Harfleur in 1415 and followed this up with a stunning victory at the Battle of Agincourt on 25 October. Caen was captured in 1417, and by 1419, Henry had managed to conquer all of Normandy, including the capital Rouen. These victories, but most especially Agincourt, where much of the French nobility had been butchered, had made Henry V a national hero, and in May 1420 he obliged the French to sign a peace treaty, the Treaty of Troyes, with very generous terms. The English king was nominated as the regent and heir to Charles VI and, to cement the new alliance, Henry married Charles' daughter, Catherine of Valois (l. 1401 - c. 1437). This was the apex of English success in the war. A condition of the deal was that Henry had to promise he would continue fighting against the Burgundian's number one enemy: the now disinherited Dauphin Charles (Charles VI's blood heir), thus perpetuating the Hundred Years' War for another round of conflict.

In March 1421, the English lost at the Battle of Baugé and Henry's own brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence was killed. Henry headed to France to resume the war personally, and on 11 May 1422, he captured Meaux after an eight-month siege. Henry never got the chance to become the king of France as he died unexpectedly, probably of dysentery, on 31 August 1422 at Bois de Vincennes in France. Henry's infant son became the next king, Henry VI, but neither his regents nor he when reaching maturity could stop a grand French revival which included the heroic efforts of Joan of Arc.

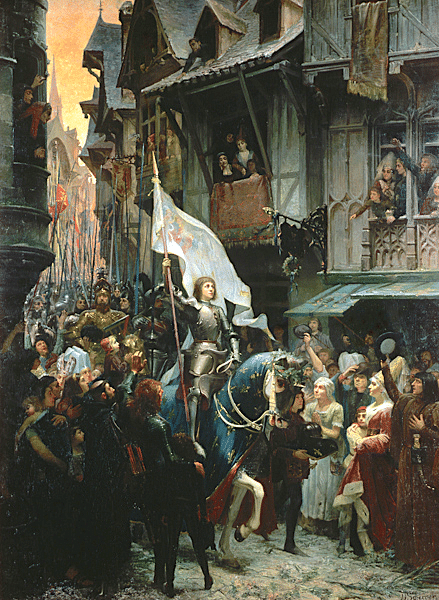

Joan of Arc, a peasant girl inspired by heavenly visions, helped dramatically lift the siege of Orleans in 1429 which marked the beginning of a French revival as the Dauphin, now King Charles VII of France, took the initiative in the war. 1429 also saw the French victory at the Battle of Patay (18 June) where English archers were effectively surrounded by French cavalry. Henry VI of England had continued to press his family's claim for the French throne, eventually being crowned as such in the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris in December 1431, but this was a sham without real substance. For England, the war now largely became one of defence rather than attack. Sir John Talbot (1384-1453), the great medieval knight known as the 'English Achilles', did win victories thanks to his aggressive tactics and surprise attacks, successfully defending both English-held Paris and Rouen. However, France was now too rich in men and resources to be stopped for very long. In 1435 the English crucially lost the support of their allies the Burgundians when their leader Philip the Good of Burgundy joined with Charles VII, by the Treaty of Arras, to end the French civil war. In 1435 Dieppe was captured, 1436 saw the French regain Paris, and in 1440 Harfleur was taken back, too.

On 22 April 1445, both the marriage of Henry to Margaret of Anjou (d. 1482), niece of Charles VII, and the giving up of Maine indicated the English king's clear aversion to continuing the war with France. Charles VII, in contrast, was utterly determined and began to retake parts of Normandy from 1449; he won the battle of Formigny in 1450, blockaded Bordeaux in 1451, and captured Gascony in 1452. At the wars' end in July 1453 and the French victory at the Battle of Castillon, the English Crown only controlled Calais. The French Crown then went on, by a mixed strategy of conquest and marriage alliances, to bring such regions as Burgundy, Provence, and Brittany together into one nation-state that was richer and more powerful than ever. England meanwhile sank into bankruptcy and civil war. Henry VI suffered from bouts of insanity, and his weak reign finally came to a sticky end when he was murdered in the Tower of London in May 1471.

Consequences of the War

The Hundred Years' War had many consequences, both immediate and long-lasting. First, there was the death of those in battle and those civilians killed or robbed by marauding soldiers between battles. A high number of French nobles were killed in the conflict, destabilising the country as those that remained squabbled for power. In England, the opposite was true as kings created ever more nobles in order to tax them and fund the war. This was not enough, though, and England ultimately arrived on the brink of bankruptcy because of the enormous cost of placing field armies in another country. Although the English had won some great victories, the final result was the loss of all territory in France except Calais. Trade was negatively affected, and the peasantry had to endure endless rounds of taxation to pay for the war, resulting in several rebellions such as the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Even the medieval church suffered as kings diverted taxes meant for the Pope in Rome and kept them for themselves to pay for their armies, resulting in the churches in England and France taking on a more 'national' character of their own.

The loss of the war for England caused many nobles there to question their monarch and his right to rule. This, and the inevitable search for scapegoats for the debacle in France, ultimately led to the dynastic disputes known today as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487).

Military technology developed over the period, in particular, the use of more efficient gunpowder weapons and the strengthening and adaptation of castles and fortified towns to meet this threat. In addition, by the war's end, Charles VII had created France's first permanent royal army.

Some of the more positive consequences were the centralisation of government, increases in bureaucratic efficiencies, and a more regulated tax system. The English Parliament, which had to meet to approve each new royal tax, became a body with a strong identity of its own, which would later help it to curb the powers of absolute monarchs. There was also a more professional diplomacy between European nations. Heroes were created, too, and celebrated in song, medieval literature and art - figures such as Joan of Arc and Henry V who, still today, are held as the finest examples of nationhood in their respective countries. Finally, such a long conflict against a clearly identifiable enemy resulted in the populations of both participants forging a much greater sense of belonging to a single nation. Even today, a rivalry still continues between these two neighbouring countries, now, fortunately, largely expressed within the confines of international sporting events.