The Hussite Wars (1419 to c. 1434) were a series of conflicts fought in Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic) between followers of the reformer Jan Hus and Catholic loyalists toward the end of the Bohemian Reformation (c. 1380 to c. 1436). Although the Catholics won, the Hussites were granted the freedom of religion they had fought for.

The wars were a direct response to the execution of Jan Hus (l. 1369-1415) in 1415 and that of his friend and colleague Jerome of Prague (l. 1379-1416) a year later after they had been condemned as heretics by the Catholic Church. The Bohemian Reformation, the first systematic attempt by Catholic clergy to reform the corruption and abuses of the medieval Church, had been underway since c. 1380 but became more radicalized after 1416, leading to the beginning of social unrest in 1419 when the Hussite Jan Želivský (l. 1380-1422) led a procession through the city that resulted in the First Defenestration of Prague on 30 July and the deaths of seven town council members.

Hus and Jerome were elevated to martyrs (later to saints), and Hus' followers were deeply devoted to his cause, but they were not a unified coalition. All that united them was their common enemy of the Catholic Church and the Catholic forces under the king of the Holy Roman Empire, Sigismund of Hungary (l. 1368-1437) who had been given permission by the pope to lead the crusade against Bohemian heresy. As soon as the Hussite general Jan Žižka (l. c. 1360-1424) defeated Sigismund in an engagement – as he did every time they met in battle – the Hussite factions would turn on each other.

Žižka, a brilliant tactician, made use of firearms and wagon forts in both defense and offense, continually surprising his opponents with the maneuverability of his mobile fortifications. The Hussite Wars are commonly referenced for Žižka's tactics and the early use of firearms in European military conflicts.

Žižka died of the plague in 1424 and was replaced by the general Prokop the Bold (also given as Prokop the Great, l. c. 1380-1434), also an effective military leader. He had no more success in unifying the Hussites after engagements than Žižka had, however, and at the Battle of Lipany in 1434 moderate Hussites sided with the Catholics against the more radical faction. The moderates (Utraquists) and Catholics defeated the radicals (Taborites), ending the conflict. Afterwards, the Utraquists were granted freedom of religion at the Council of Basel in 1346, ending both the Hussite Wars and the Bohemian Reformation, although issues concerning religion would continue to cause conflict afterwards.

Background

Although the Hussite Wars were sparked by the execution of Hus, the Bohemian Reformation had been underway for decades, and calls for reform, as well as antagonism toward the Roman Catholic Church, were nothing new. Priests and theologians in Bohemia had been advocating for reform since before 1380. The Church had split into the Roman Catholic Church in the West and the Eastern Orthodox Church in 1054 (the Great Schism) which, to many reformers, suggested serious problems in its vision and policies.

The Bohemian Church was established by missionaries from the Eastern Orthodox Church but was then left to be developed by Roman Catholic policies. Consequently, the clergy of Bohemia was slow to accept and implement these policies as they had initially been left to develop their own. The authority of the Church of Rome was further challenged in Bohemia when it divided during the Western Schism (1378-1417) in which there were two, and then three, popes all claiming to be the legitimate pontiff and all requiring tribute from the people. Scholar Francis Lutzow comments:

In consequence of its geographical position, Bohemia for a long time suffered less from the extortions of the Roman pontiffs than many other countries did. Only when, in consequence of the schism, the rival popes found that the number of countries from which they could derive funds was diminishing, the claims of Rome on Bohemia became more urgent and more frequent. The discontent caused by the rapacity of the rival pontiffs, whose violent controversies did not raise the Western Church in the esteem of the Bohemian people, found a center in the University of Prague. (12)

Jan Hus was appointed rector of the University of Prague in 1402, the same year he was introduced to the works of the English reformer John Wycliffe (l. 1330-1384) by his friend Jerome of Prague. Wycliffe had denounced the abuses and unbiblical policies of the Church in England, specifically citing the sale of indulgences as nothing but avarice and questioning the authority of the pope as well as the Church's policy of land ownership among other serious corruptions of Jesus Christ's teachings.

Hus was deeply influenced by Wycliffe's writings and began preaching his own ideas concerning reform at two sermons given every Sunday at the Bethlehem Chapel which was founded on the understanding that services would be conducted in Czech, not Latin. Consequently, he was able to speak directly to his congregation (who did not know Latin, the language used in Catholic services) and his passion and eloquence, as well as the dissemination of his ideas through woodblock-printed pamphlets, spread the advocacy of reform throughout the region.

He was called to the Council of Constance to explain himself in 1414 under a writ of safe passage in 1414 but was betrayed, imprisoned, and executed in July of 1415. Jerome of Prague, who defended Hus, was burned at the stake a year later. Hus' supporters, known as Hussites, then began to protest the Church's policies openly, leading to the outbreak of the Hussite Wars.

First Defenestration of Prague

Although Hussite preachers immediately denounced the executions, as well as earlier ones, the first open protest was led by the priest Jan Želivský who organized a procession through Prague in opposition to the town council's decision not to release Hussite prisoners. At some point, stones were hurled from the town hall windows at the protesters, one of them striking Želivský, who responded by leading his followers into the building and hurling seven town council members out the upper-storey window to their deaths – an event known as the First Defenestration of Prague (as there would be others). Scholar Brad S. Gregory comments:

On July 30, 1419, the radical preacher Jan Zelivsky led the demonstration that issued in the defenestration of Prague and the Hussite takeover of the city. A week earlier, he had blasted the authorities responsible for executing the martyrs: "To kill out of malice is murder," he said. "This is what took place in Constance, hence everyone is a murderer who consented to the death of Master John Hus and Jerome, as well as to the death of the laymen who were beheaded in the Old City of Prague and those who were burned." (69)

The killing of the town council members shocked the authorities and, according to legend, so upset King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia that he died of a stroke upon hearing of it. His half-brother, Sigismund of Hungary, appealed to the pope for permission to launch a crusade against the heretics of Bohemia, and the Hussite Wars began. Hussites were arrested and burned at the stake, and in 1422, Želivský was captured, turned over to the town council of Prague, and executed.

First Crusade & Vítkov Hill

Wenceslaus IV's widow, Sophia, had been an admirer of Hus but now prepared a mercenary army and launched it against the Hussites of Prague, destroying half the city. Sigismund received permission to carry out his crusade by Pope Martin V in March of 1420 and was joined by several of the German nobility who were as interested in personal gain through plunder as whatever remittance of sin the Church was offering for participation. The crusaders caught the Hussite forces on an open plain, outnumbering them roughly 2,000 to 400 but were defeated by the tactics of Jan Žižka in what came to be known as the Battle of Sudoměř (25 March 1420). This was Žižka's first use of his war wagon innovation as well as one of the most famous examples of his brilliance in choosing the optimal ground for an engagement.

After this Hussite victory, the crusade continued. Sigismund and his army lay siege to Prague and offered to negotiate before hostilities went further. The Hussites issued their demands in a writ known as the Four Articles of Prague, claiming the right to preach the word of God freely as they interpreted it, celebrate the sacrament of the Eucharist with the laity giving them both bread and wine, prohibit clergy from owning large estates or serving as secular authorities, and punishing those guilty of mortal sins regardless of social status.

The second article concerning the Eucharist was the rallying point for the Hussites as the Catholic Church mandated that laity only be given the bread at communion, the wine being reserved for the priest alone. This stipulation epitomized the Church's abusive control of power to the Hussites, who saw in it as another attempt to separate the people from communion with God, just as they felt celebrating Mass in Latin, the Latin Bible, and Latin prayers did.

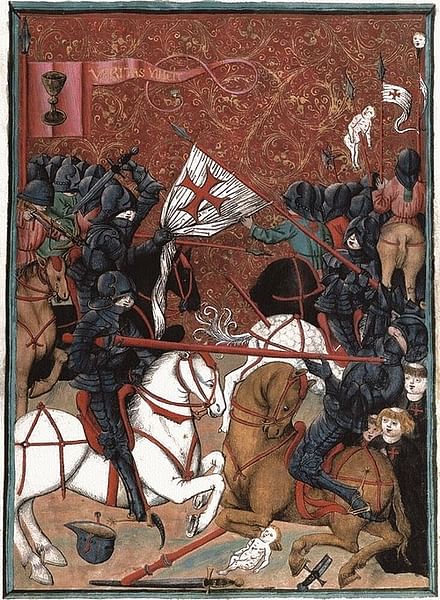

The concept of "freedom of the chalice" was known as utraquism ("under both kinds"), referring to the freedom of the people to receive both bread and wine at communion. It was the one point all Hussites agreed upon, and the chalice was emblazoned on their standards and shields. There were many different factions of Hussites, however, including the moderate Utraquists and the more radical Taborites, and all had a different interpretation of Hus' teachings.

Sigismund rejected the Articles of Prague on the grounds they denied the authority of the Church and continued his siege. The Hussite general Jan Žižka deployed his force of less than 100 to nearby Vítkov Hill which commanded the valley below and could be held through older fortifications that were now garrisoned and defended. Sigismund's army of over 10,000 attacked the position but, owing to Žižka's brilliance in command, were driven back with heavy losses. Sigismund was forced to withdraw, and the Hussite victory drew more men and women to enlist in the defense of the land.

Wagon Forts & Second Crusade

The Hussite army had defeated heavily armored knights using primarily farm implements, crossbows, and some firearms. After Sudoměř and Vítkov Hill, Žižka understood he could use the common farming tools and carts of his peasant army to effect. His soldiers already knew how to wield a pitchfork, flail, or bow and how to harness, load, and move a wagon. He invented what came to be known as the Wagenburg (wagon fort), which were reinforced farm wagons to be used in battle. This innovation was suggested more by necessity than anything else as the Hussite forces were initially poorly equipped and lacked both military training and experience.

Each wagon fort was manned by 20 soldiers, men and women, divided into crossbowmen, gunmen, pikemen, and those using flails. The sides of the wagons that would face the enemy were thickly reinforced with wood and metal as a shield. The wagons became mobile fortresses which, in battle, were formed as a square with artillery placed behind and between each fort. The artillery would begin a barrage, usually inflicting heavy casualties, and when the enemy cavalry charged the position, handguns and crossbows would take out the horses and the pikemen, and others from the forts would fall on the dismounted knights.

Žižka used his wagon forts to effect at the culmination of Sigismund's second crusade, the Battle of Kutna Hora in December 1421. Žižka positioned the wagons between Sigismund's forces and the town but, as Sigismund was steadily reinforced, soon found himself surrounded. On 21 December, rather than face surrender, Žižka organized the wagons in a column and led them against Sigismund's army. Every wagon kept up a continual barrage from firearms, crossbows, and an early form of the howitzer, breaking the enemy's lines. Žižka led his traveling fortresses away from the site while Sigismund dealt with his dead and wounded and chose not to pursue.

Žižka & Unity

Although Žižka was able to unite the disparate Utraquists, Taborites, and others in battle, as soon as victory was achieved, the factions attacked each other over doctrinal differences. In an effort at maintaining order, Žižka sent word to King Władysław II of Poland, offering him rule of Bohemia, but he refused. Žižka then approached his cousin, Vytautas, who accepted, but only if the Hussites surrendered and recognized the authority of the Church, which Žižka refused to do. The Lithuanian prince Sigismund Korybut accepted, without conditions, and was recognized as legitimate by the Hussites, but before he could initiate any progress, he was forced to return to Lithuania under pressure from Sigismund of Hungary.

As soon as Prince Sigismund Korybut was gone, the Utraquists and Taborites fell upon each other again. Žižka led the Taborites to victory against the Utraquists in April 1423, resulting in a temporary truce, but this would not last long, and their attempt at invading Moravia later in the year failed completely due to their lack of unity. Žižka died in October of 1424 from the plague, still undefeated, and was replaced by Prokop the Bold who, with Sigismund Korybut, continued Hussite victories through 1426.

The Battle of Lipany

The pope called for a third crusade against the Hussites, but none of the neighboring kingdoms were interested in doing anything about it, even though Prokop the Bold had initiated the policy of the Glorious Rides – raids against kingdoms that had supported the earlier crusades – sacking areas of Hungary, Meissen, Saxony, and others. Again, as under Žižka, the Hussites fought well together as a unified force when presented with a common enemy but could not maintain this unity after victories.

Tensions finally led to the Battle of Lipany on 30 May 1434 when the Utraquists allied themselves with the Catholic loyalist forces against the Taborites. The Taborites were commanded by Prokop the Bold and the general Jan Čapek of Sány, who led the cavalry. Prokop made strategic use of the wagon forts, but he was now facing an enemy who had previously fought under him and knew his tactics.

Prokop's initial offensive barrage from the wagon forts seemed to force the opposing army into retreat, and he opened the forts so his soldiers could pursue. The retreat was a feint, however, and the Utraquist forces turned and attacked at the same time their cavalry, hidden until then, took the field. Prokop was killed in battle, and his forces were massacred. Survivors were later burned as heretics.

Conclusion

The Battle of Lipany effectively ended the Hussite Wars, and an official peace accord was reached two years later at the Council of Basel. The Hussite platform at this time was influenced by the pacifist priest, thinker, and writer Petr Chelčický (l. c. 1390 to c. 1460) who had denounced the violence as anti-Christian. Chelčický's views formed the central vision of the Unity of the Brethren, who would advocate further reforms peacefully.

After millions had been killed and the land ravaged between 1420 and 1436, the Four Articles of Prague were accepted, in a modified form, by the Catholic Church at the Council of Basel. The Utraquists were granted the religious freedom they had fought for as they were considered "redeemed" through their abandonment of the Taborites at Lipany.

Although they would have further disagreements with the Church, the Utraquists later modeled themselves on the hierarchy of the Church and even sought its approval for the ordination of clergy. In time, the Utraquists became the religious authority in Bohemia and persecuted those who disagreed with them, just as the Roman Catholic Church had once persecuted them.