The Hyksos were a Semitic people who gained a foothold in Egypt c. 1782 BCE at the city of Avaris in Lower Egypt, thus initiating the era known in Egyptian history as the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE). Their name, Heqau-khasut, translates as 'Rulers of Foreign Lands' (given by the Greeks as Hyksos), suggesting to some scholars that they were kings or nobility driven from their homes by invasion who found refuge in the port city of Avaris and managed to establish a strong power base during the decline of the 13th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE). Most likely, they were traders who were at first welcomed at Avaris, prospered, and sent word to their friends and neighbors to come join them, resulting in a large population which was able to finally exert political and then military power.

Although the later Egyptian scribes of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) would demonize the Hyksos as 'invaders' who conquered the land, destroyed temples, and slaughtered without mercy, there is no evidence for any of these claims. Even today, the Hyksos are referred to as invaders and their advent in Egypt as the 'Hyksos Invasion,' but actually, they assimilated neatly into Egyptian culture adopting Egyptian fashion and religious beliefs, with some modifications, as their own. Contrary to many claims throughout the years, there is no reason to identify the Hyksos with the Hurrians nor with the Hebrew slaves from the biblical Book of Exodus.

The main source of information on the Hyksos in Egypt comes from the 3rd century BCE Egyptian writer Manetho whose work has been lost but was extensively quoted by later writers, notably Flavius Josephus (37- c. 100 CE). Manetho's flawed understanding of the meaning of the Hyksos' name, and Josephus' further misinterpretation gives the translation of 'Hyksos' as 'captive shepherds,' and this complete misunderstanding has given rise in recent years to the claim that the Hyksos were a Hebrew community living in Egypt whose expulsion provides the basis for the events recorded in the Book of Exodus. There is no evidence, however, to support this claim. No Egyptian, nor any other culture's, records indicate the Hyksos were slaves in Egypt, and there is absolutely no indication they were Hebrew, only that they spoke and wrote a Semitic language. The ethnic origins of the Hyksos are unknown as is their fate once they were driven from Egypt by Ahmose I of Thebes (c. 1570-1544 BCE) who initiated the era of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-1069 BCE).

The Arrival of the Hyksos

For the greater part of Egypt's history, the country was insular even though foreigners regularly came to work in the country, serve as mercenaries, or were taken as slaves for the gold mines. Egyptians lived in the land of the gods, and those of lesser quality (regularly referred to as 'Asiatics') were off beyond the borders. The popular story of The Contendings of Horus and Set from the New Kingdom relates how, once the god Set is bested by Horus, he is given a kind of consolation prize of ruling over the desert regions beyond Egypt's borders. Set had murdered his brother, the god-king Osiris, and usurped the rule of Egypt. Osiris was brought back to life by his sister-wife Isis who bore his son Horus, the god who would eventually avenge his father and restore order to the land. The story's conclusion of placing Set outside of Egypt's borders is significant because Set was considered the god of chaos, darkness, storms and winds, and the Egyptians would have wanted such a deity as far from them as possible; out in the wilds where the 'other people,' the 'Asiatics,' would get the kind of god they deserved.

Early campaigns by the Egyptian military, up until the time of the New Kingdom, were domestic for the most part, and when Egyptians did travel beyond their borders, it was never far. When the Hyksos first arrived, therefore, they would not have posed any great danger to Egyptian security because an actual threat from outside the country was simply unthinkable. By c. 1782 BCE, Egypt had developed as a civilization for over 2,000 years, and the possibility of a people taking their country would have been dismissed as easily as a full-scale invasion of earth by flying saucers from Mars would be by most people today.

When the period of the Middle Kingdom began, Egypt was a strong, unified country. The king Amenemhat I (1991-1962 BCE), who founded the 12th Dynasty, was a strong, effective, ruler who, perhaps in an effort to further unify the country, moved the capital from Thebes (in Upper Egypt) to a middle ground between Upper and Lower Egypt near Lisht and named his new city Iti-tawi (also Itj-tawi) which means "Amenemhat is he who takes possession of the Two Lands" (van de Mieroop, 101). He also founded the town of Hutwaret in Lower Egypt as a port of trade. Hutwaret (better known as Avaris, the Greek name) had access to the Mediterranean Sea and overland routes to the region of Syria-Palestine.

The 12th Dynasty is considered by many the high point of Egyptian culture and gives the Middle Kingdom its reputation as the 'classical age' of Egypt. The 13th Dynasty, however, was not as strong and made a number of ill-advised decisions which weakened their influence. The first of these mistakes was to move the capital from Iti-tawi back to Thebes in Upper Egypt. This decision essentially left Lower Egypt open to whatever power felt it had enough support to dominate it. The port town of Avaris, quickly expanding into a small city through commerce, attracted many of the people known to the Egyptians as 'Asiatics,' and as it flourished, their population grew. The Hyksos gained control of the eastern Delta commercially and then moved north making treaties and forging contracts with various nomarchs (governors) of other regions in Lower Egypt until they had taken a sizeable amount of the land and were able to exert political power.

The Hyksos in Egypt

Contrary to the claims of New Kingdom scribes, Manetho, Josephus - and even later historians of the 20th century CE - the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt was not a time of chaos and confusion, and the Hyksos did not conquer the whole of Egypt. Their influence extended only as far south as Abydos, and in the region of Lower Egypt, there were many cities, like Xois, which maintained their autonomy. The ruling class of Xois founded the Xoite Dynasty (the 14th Dynasty of Egypt) during the time of the Hyksos and traded regularly with both them and Thebes.

Josephus' account, relying heavily on Manetho's (who drew on the New Kingdom scribes) gives the impression that the Hyksos rolled into Egypt in their war chariots, laying waste to the land, and toppling the legitimate government. Again, there is no evidence for this; Egyptologist and historian Margaret Bunson explains:

The Hyksos did enter Egypt, but they did not appear there suddenly, with what Manetho termed "a blast of God". The Hyksos entered the Nile region gradually over a series of decades until the Egyptians realized the danger they posed in their midst. Most of the Asiatics came across Egypt's borders for centuries without causing much of a stir. (119)

Once they were established at Avaris, the Hyksos placed Egyptians in significant positions, adopted Egyptian custom and dress, and incorporated the worship of Egyptian gods into their own beliefs and rituals. Their chief gods were Baal and Anat, both of Phoenician/Canaanite/Syrian origin, but they identified Baal with the Egyptian Set.

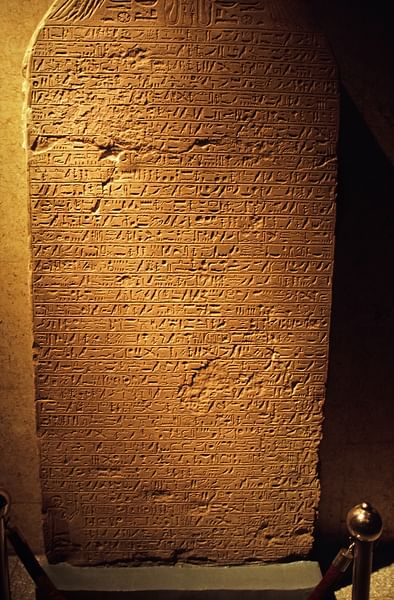

The Hyksos rulers founded the 15th Dynasty of Egypt, but after they were expelled, all traces of the Hyksos in Egypt were erased by the conquering Thebans. Only a few Hyksos kings are known by name from the ruins of inscriptions, and other writings, found at Avaris and beyond: Sakir-Har, Khyan, Khamudi, and the best known, Apepi. Apepi was also known as Apophis and interestingly has an Egyptian name associated with the great serpent Apophis/Apep, enemy of the sun god Ra. It is possible that this king, who allegedly initiated the conflict between Avaris and Thebes, was so named by later scribes to associate him with danger and darkness.

There is nothing in the evidence which suggests that Apepi was either of those things. Trade flourished during the time of the Hyksos. Local governors of the cities and towns of Lower Egypt made treaties with the Hyksos, enjoyed profitable trade, and even Thebes, consistently depicted as the "last holdout" of Egyptian culture standing alone against the invader, had a cordial and seemingly profitable relationship with them, even though it does seem that Thebes paid tribute to Avaris.

Avaris, Thebes & War

At the same time the Hyksos were gaining power in northern Egypt, the Nubians were doing so to the south. The 13th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom had neglected to pay attention to their southern border just as they had with Lower Egypt. Thebes remained the capital of Upper Egypt but, instead of ruling the entire country, was sandwiched between the Hyksos in the north and the Nubians in the south. Still, Thebes and Avaris got along quite well. The Thebans were free to trade to the north, and the Hyksos sailed their ships past Thebes to buy and sell to the Nubians in the south. Trade went on between the Nubian capital of Kush, the Egyptian center at Thebes, and Avaris quite evenly until the Hyksos king - wittingly or unwittingly - insulted the king of Thebes.

There is no telling whether the story is true as given, but according to Manetho, Apepi of the Hyksos sent a message to the Theban king Seqenenra Taa (also known as Ta'O (c. 1580 BCE): "Do away with the hippopotamus pool which is on the east of the city, for they prevent me sleeping day and night." The message most likely had to do with the Theban practice of hippopotamus hunting, which would have been offensive to the Hyksos who incorporated the hippo in their religious observances through their worship of Set. Instead of complying with the request, Ta'O interpreted it as a challenge to his autonomy and marched on Avaris. His mummy shows he was killed in battle and this, and the events which follow, suggests the Thebans were defeated in this engagement.

Ta'O's son Kamose took up the cause, complaining bitterly in an inscription that he was tired of paying "the Asiatics" taxes and having to deal with foreigners to the north and south of him in his own land. He launched a massive strike against the Hyksos in which, according to his own account, Avaris was destroyed. Kamose claims that his attack was so swift and terrifying it made the Hyksos women suddenly sterile, and after the slaughter, he razed the city to the ground. This account would seem to be something of an exaggeration since the Hyksos still held Lower Egypt in the three years following Kamose's offensive and Avaris still stood as the Hyksos stronghold.

Kamose was succeeded by his brother Ahmose, whose inscriptions describe how he drove the Hyksos from Egypt and destroyed their city of Avaris. These events are given in the tomb inscriptions of another man, Ahmose son of Ibana, a soldier who served under the king Ahmose, describing the destruction of Avaris and the flight of the surviving Hyksos to Sharuhen in the region of Palestine. This city was then placed under siege by Ahmose for six years until the Hyksos fled again, this time to Syria, but what happened to them after that is not recorded.

The Legacy of the Hyksos in Egypt

Ahmose I not only founded the 18th Dynasty but initiated the period of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era of the Egyptian empire. The development of a professional Egyptian army of conquest can be directly traced to the Hyksos in that Ahmose I, and those who followed him, wanted to make sure no foreign people would ever be able to gain such power in their land again. Beginning with Ahmose, and continuing on throughout the New Kingdom, the pharaohs created and maintained a buffer zone around Egypt which then encouraged them to conquer more lands beyond.

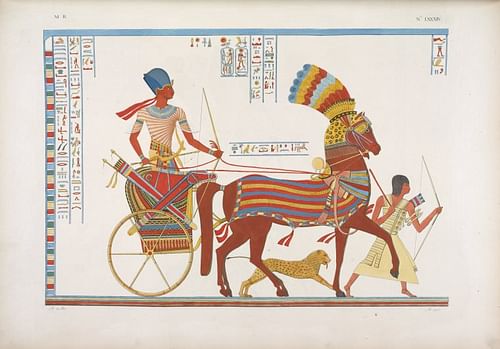

The Hyksos were vilified by the New Kingdom scribes to justify these wars of conquest and a new version of history was created in which the foreign invaders destroyed the temples of the gods, slaughtering the innocent and razing cities in a barbaric lust for conquest. Besides the fact that none of that happened, if it were not for the Hyksos, the Egyptian army would have been without two advantages which helped them establish their empire: the composite bow and the horse-drawn chariot.

Egyptian art from the New Kingdom regularly depicts the pharaoh, kings such as Tutankhamun or Ramesses II, in their chariot hunting with their dogs or going to war, and since the New Kingdom is the period most familiar to people in the present day, the chariot is associated with Egypt. The Egyptians had no knowledge of it, however, until it was introduced by the Hyksos. The composite bow, with much greater range and accuracy, replaced the Egyptian long bow that had been in use for centuries and the Hyksos also introduced the bronze dagger, the short sword, and many other innovations. New methods of crop irrigation were introduced to Egypt as well as metalworking in bronze. An improved potter's wheel resulted in higher quality ceramics which were also more durable. The Hyksos also brought to Egypt the vertical loom, which produced better quality linen, and new fruit and vegetable cultivation techniques.

The innovations of the Hyksos transformed the culture of Egypt but they also preserved the past. Under Apepi, old papyrus scrolls were copied and carefully stored and many of these are the only extant copies to have survived. They also united Egypt as never before through their depiction by New Kingdom scribes as blood-thirsty conquerors who had invaded the land of the gods. Egyptian nationalism was at an all-time high throughout most of the period of the New Kingdom, and aside from the new and improved weapons, Egypt's empire could never have risen without the belief that conquest was necessary to protect the people of Egypt from another tragedy which might be even more terrible than the invasion of the Hyksos.