An ice age is a period in which the earth's climate is colder than normal, with ice sheets capping the poles and glaciers dominating higher altitudes. Within an ice age, there are varying pulses of colder and warmer climatic conditions, known as 'glacials' and 'interglacials'. Even within the interglacials, ice continues to cover at least one of the poles. In contrast, outside an ice age temperatures are higher and more stable, and there is far less ice all around. The earth has thus far made it through at least five significant ice ages.

One glance at our icy poles and frozen peaks makes it clear that our current epoch (the Holocene, c. 12,000-present day) actually represents an interglacial within the ice age that spans the Quaternary geological period, which started around 2,6 million years ago and encompasses both the Pleistocene (c. 2,6 million years ago - c. 12,000 years ago) and the Holocene epochs. This entire period is characterised by cycles of ups and downs in ice sheet volumes and temperatures which can sometimes change as much as 15°C within a couple of decades. This rapidly overturning climate can have huge knock-on effects all around the world, altering vegetation and the types of animals that can survive in certain areas, and it helped shape human evolution, too. It is because of its connection with our own story that this definition will largely focus on the Quaternary ice age, and mostly on the to us more unfamiliar world of the Pleistocene, with its magnificent mammoths and long-toothed cats surviving alongside early human hunter-gatherers weaving their way through these volatile conditions.

Climate

After the Antarctic ice sheet first began to spread its chilly fingers through the world's oceans around 38 million years ago, the cooling oceans allowed for the earth's temperature swings to become stronger and stronger. A major cooling-down step occurred around 2,6 million years ago at the start of the Quaternary, and it was followed by steps around 1,8 million years ago, c. 900,000 years ago, and c. 400,000 years ago that became ever harsher.

This increasing strength is especially noticeable from around 900,000 years ago onwards, as it was not until this point that major glaciations - with sweeping ice sheets covering higher altitudes across Eurasia and North America – became common features of the Quaternary ice age. From this time on, survival was definitely no walk in the park but required coping with much more extreme conditions. During the cold swings, temperatures could reach up to a terrifying 21°C colder than the present, although the average lies closer to 5°C colder than today. During Quaternary glaciations in general, because of the amount of water stuck in frozen form, sea levels could be up to 120 meters lower than they are now. A lot more land was thus left uncovered for species to explore, and places such as the British Isles could suddenly be reached because the North Sea would turn into a sort of North Land during these times. Meanwhile, while the earth's northern reaches were covered by tundra, Africa became drier.

Glacial climates – which varied in strength, effect, and affected different areas in different ways – generally crept up quite gradually, beginning with cooler and wetter conditions that eventually climaxed in a cold and dry phase. The ice sheets grew so thick that they would cling on for a while into the start of a warming trend, only to collapse suddenly, leading to a very sudden switch into an interglacial. Temperatures could then remain quite peachy for a good while, and the world saw higher sea levels and actually accessible higher latitudes. During the last ~1,2 million years, these cycles were generally around 100,000 years in length.

For species to be able to adapt to these fickle conditions is not an easy task, especially considering the speed at which things could change.

Faunal diversity

The cover girl of the Pleistocene is without a doubt the woolly mammoth; huge, towering, curved-tusked, shaggy-coated foragers related to elephants. They actually originated in Africa and during the Pleistocene set out on a trek towards the northern tundras. They were not the only species that flourished during this period. The appearance and expansion of, among others, the genus Equus (which includes horses and zebra), bison, aurochs, hippopotamus, giant ground sloths, voles, the deer family (among which oversized versions such as Megaloceros or Giant Deer, and the moose genus), and the second woolly powerhouse – the woolly rhinoceros – filled in the prehistoric landscape.

The predators wanting to feast on such diversity did not lag behind; sabre-toothed cats (who were generally not closely related to cats) munched away on prey throughout the Pleistocene, and lions ranged all the way from southern Africa to southern North America during the late Pleistocene, including cave lions that lived all the way from Europe to western Canada. Caves were popular; cave bears could be found throughout Europe and Asia up to the northeast of Siberia, and the same goes for the cave hyena.

The disappearance of the megafauna

Such diversity is hard to imagine from our own point of view, in a time when humans have shaped the world to suit their own needs to such an extent the habitats of many animals have already shrunk or disappeared completely. Indeed, a lot of the creatures named above have long since vanished from the face of the earth. Quite a few of the big ones, in particular, collectively referred to as the Pleistocene megafauna, seem to have dwindled and died out towards the end of the Pleistocene in a massive extinction event.

The last of the cave bears seem to have met their end somewhere between c. 30,500 - c. 28,500 years ago, around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (the most recent glacial, in which the ice sheets reached peak growth between c. 26,500 to c. 19,000 years ago). In fact, the northern reaches of Eurasia saw as much as around 37% of species weighing upwards of 44 kg disappear from this time onwards. Species such as cave lions and woolly rhinoceros clung on until c. 14,000 years ago, the latter already having retreated far into northeastern Siberia as a final refuge by this time, seemingly having trouble dealing with the late-glacial warming climate (which also affected the plants it normally ate).

Our iconic mammoth actually survived into the Holocene (alongside the Giant Deer, which is last known from the Urals in Siberia around 7700 years ago), albeit pushed back to a last retreat at Wrangel Island in Arctic Siberia where it finally gave in c. 3600 years ago. This is one species on which the impact of climate change can clearly be seen, as after the Last Glacial Maximum ended, the warmer conditions seem to have made a serious dent into the mammoths' climatic niche, and their numbers plummeted. We know that humans also hunted them quite successfully, and it seems the challenging climate left the mammoths quite vulnerable.

This combination of climatic as well as human-induced effects was arguably the culprit when it came to the extinction of more of these Pleistocene favourites, including the Eurasian steppe bison and the wild horse. The finer details are subject to fierce discussion, though.

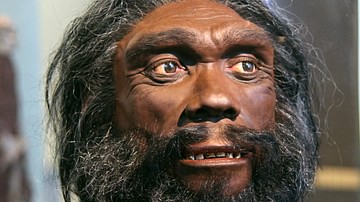

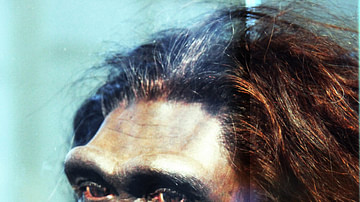

Early humans

As with the other fauna, prehistoric humans were directly impacted by the unpredictable Quaternary climate. In fact, it seems that our survival and development was actually shaped by the rapid shifts in conditions that came with the Ice Age; all the big benchmarks of species appearance within our evolutionary history, as well the appearance of the different stone technologies, can be linked to periods of very high climatic variation. Humans thus had to be able to adapt not just, for instance, to rainy forests but also arid grasslands, and the ones who were good at this obviously did better than their more limited peers. As such, humans became ever more resourceful.

Adaptability also means it became possible to move to entirely new areas and learn to cope with their specific quirks and to take advantage of them. Around 870,000 years ago, for instance, there was a marked drop in temperature which pushed large herbivores into southern Europe and opened up a corridor through the Po Valley, of which Homo heidelbergensis seems to have been keenly aware. Within Europe, they then learned to ebb and flow along with the growth and decline of the glaciers and carved out some nice spots for themselves.

The climatic variations also opened up green corridors across the Sahara between roughly 50,000 – c. 45,000 years ago and c. 120,000 – c. 110,000 years ago, interestingly, their appearance coincides with the main migrations of Homo sapiens out of sub-Saharan Africa. Lower sea levels consequently even left Australia within reasonable striking distance, and Beringia was turned into steppe land during the cold snaps, forming a possible passageway for humans into the Americas.

While Homo sapiens flourished in the Late Pleistocene and spread out far and wide, the Neanderthals were not so lucky; while Eurasia was cooling down on its way to the Last Glacial Maximum, it seems their numbers grew smaller. Whether due to climatic conditions, extinction of their prey, competition with the Homo sapiens who arrived after c. 45,000 years ago, a combination of these things or something else entirely, the Neanderthal species (disappeared around 30,000 years ago) can be added to the list of those who did not survive the most recent glacial that took hold of the world. Crucially, the fluctuations in temperature that come along with the glacials and interglacials described in this article are the result of natural processes, whereas today's threat posed by global warming is one that is induced by us humans.