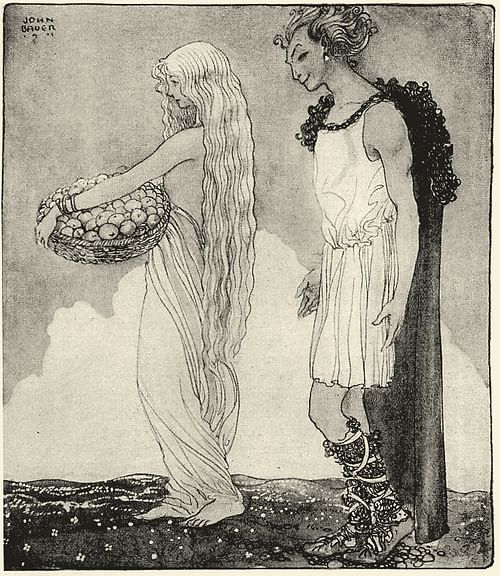

Idunn (pronounced Ih-dune) is a fertility goddess in Norse mythology who holds the apples of eternal youth the gods rely on to remain young and healthy. The Norse gods were not immortal – they just lived very long lives – and the apples of Idunn made this possible.

It is thought that, originally, the apples were some other fruit that was replaced by the apple in the Prose Edda of the 13th century by the Icelandic mythographer Snorri Sturluson (l. 1179-1241), a Christian writing for a Christian audience. The earlier 10th-century poem Haustlöng featuring the same story of Idunn’s abduction does not mention apples. Although the apple is never specified in the Bible as the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden, it had already become associated with the story from Genesis by Sturluson’s time and would have been recognized by his audience as a fruit associated with the supernatural.

The apple image might also have been borrowed from Greek mythology (the golden apples of the Hesperides) as golden apples appear in another Norse tale from the 10th century. The fact that the Haustlöng makes no mention of them, however, suggests they were a later addition to this particular story. Originally, Idunn may have represented the concept of personal and familial luck and power (hamingja) generating an eternal youth for herself and the other deities in the same way a mortal family carried on the memory of the deeds of their ancestors – and so kept them forever young and alive – without mystical apples.

Idunn only appears in two tales from Norse mythology, a section of the Skáldskaparmál of the Prose Edda retelling Idunn’s abduction from Haustlöng, and the Lokasenna of the Poetic Edda. Although rarely mentioned, she is the power behind all of the better-known deities as she allows them to retain their youth and vitality. It has been suggested that Idunn herself is the source of this power, not the apples, and the fruit she offers the other gods and goddesses is only the physical manifestation of her own innate abilities to ward off sickness, old age, and death while encouraging life, health, and personal growth. She is a goddess of choice in modern-day Wiccan and Neo-Pagan religious movements for this very reason and is often invoked for health, rejuvenation, second chances, and healing.

Name & Character

Idunn (also given as Ydun, Idun, Ithunn, and Idunna) means "ever young" or "the rejuvenating one" and defines her as a fertility goddess who encourages the lifeforce. The Haustlöng references her as the one who holds "the old-age cure" of the gods and as "the maiden who understood the eternal life of the Aesir" (the deities of Asgard) and kept them young. She may have evolved as a later figure with a single responsibility from the earlier goddesses Frigg and Freyja who are themselves thought to be later versions of the Germanic goddess Frija.

Freyja and Frigg are both powerful fertility goddesses who may have once been envisioned as keeping the other deities young before that job was given to Idunn who was the wife of Bragi, god of poetry. Poetry was highly valued by the Norse culture for many reasons but, chiefly, as a means of preserving one’s deeds and celebrating one’s life. The subject of a poem lived on long after their death and this may have associated Bragi with the concept of eternal youth resulting in the job of keeping the gods young being transferred from Frigg, Freyja, or both, to Idunn.

However she came to the role, Idunn is understood as one of the many powerful female deities of the Norse pantheon. Scholar H. D. Ellis Davidson comments:

While the ruling gods are warrior leaders, ruling a male world, there is nevertheless a strong female element in the mythology as it has come down to us. The goddesses are figures of tremendous vitality both in generous giving and destruction, and seem to represent ultimate destiny, before whom the gods themselves must go down fighting. The image of spinning, weaving women deities overshadows those of human heroes and ruling gods. The women are present in the myths; they stalk across the newly created world in the opening section of Völuspá and survive in humble folktales of later times, punishing the arrogant and cruel and helping the young and innocent to win good fortune. (226)

The best example of Davidson’s claim is the Norns – the Fates – imagined as female, but there are also goddesses like Frigg, Freyja, Skadi (goddess of skiing, bowhunting, and mountains), and the long-suffering Sigyn, wife of the trickster god Loki, among others. Idunn holds her own among these better-known figures as the underlying power of the Aesir that enables them to perform their great deeds and is depicted as a peacemaker and defender of the innocent in the Lokasenna when Loki launches his verbal attack on her husband Bragi.

Idunn in Lokasenna

The Lokasenna ("Loki’s Taunts") is a work from the Poetic Edda (13th century) derived from an older piece. The gods of Asgard are seated at a banquet hosted by Aegir, Lord of the Sea, when Loki, jealous of the praise given to the servants, kills one of them and is thrown out of the hall. He returns, however, reminding Odin of a long-ago oath he took that he would never drink unless Loki was present. Odin must either leave the banquet or allow Loki back in and so orders a seat be given him.

Bragi objects and Loki insults him, calling him nothing more than a "benchwarmer", and Bragi responds by offering Loki a horse, sword, and ring if he will just behave himself and not insult or anger the guests. Loki insults Bragi again, calling him a coward and the poorest among the gods, which rouses Bragi’s anger. At this point, Idunn comes between them and speaks to her husband:

I beg you, Bragi,

Think of your children

By Blood and adoption,

And don’t slander even Loki

Here in Aegir’s Hall.

Loki responds:

Silence, Ithunn.

I don’t think there’s any woman

More lustful than you.

Not since you wrapped

Your pretty arms

Around the killer of your brother.

Idunn replies:

I will not slander even Loki

Here in Aegir’s Hall.

I will calm you,

Beer-maddened Bragi;

I don’t want you two to fight.(Stanzas 16-18, quoted in Crawford, 104)

Loki continues to insult the other gods around the table until Thor arrives and he agrees to behave himself to avoid a beating. He is later caught by the gods, even though he tries shapeshifting to escape them, and is chained in a cave under the earth with a serpent above his head dripping scalding venom on his head. His wife Sigyn catches the venom in a bowl but, when she leaves to empty it, the serpent’s venom strikes Loki fully and he writhes in pain, causing earthquakes in the mortal realm.

Idunn is the first goddess in the poem to address the problem of Loki, and the only one who tries to diffuse the situation. Freyja and Frigg both scold Loki, but Idunn refuses to play his game and addresses Bragi, not Loki, to keep the peace. By not encouraging Loki, she hopes he will behave, but he continues his verbal taunts, accusing each of the goddesses of promiscuity and infidelity. His accusation regarding Idunn sleeping with her brother’s killer is not attested in any other work, and it is thought this charge is simply Loki spinning one of his usual lies, in this case to get a rise out of Bragi.

Idunn’s Abduction

In the Lokasenna, Idunn is presented as a peacekeeper who would rather take Loki’s insults than respond to them and encourage further trouble. Although her efforts fail overall – as Loki continues his taunts – she keeps Bragi from making good on his threat to hold Loki’s severed head as payback for his insults. Idunn’s role as keeper of the peace is emphasized here, but in the tale of her abduction, she is highlighted as the goddess who provides all the others with their essential power and lifeforce.

The story is first told in the Haustlöng and then later in the Skáldskaparmál of the Prose Edda. Odin, Loki, and Hoenir (possibly the god of intelligence and divination) are traveling and have not eaten in days. They find and kill an ox, but no matter how long they turn it over the fire, the meat will not cook. A large eagle who has been watching from the branches of a tree above them calls out that he is responsible and, if they will allow him to eat his fill, he will withdraw his magic spell and allow the meat to cook.

The gods agree, and the ox is cooked, but the eagle eats and eats, taking the best parts for himself, until Loki, enraged, swings his staff at the bird. The eagle takes to the air, casting another spell, which attaches the staff to him and Loki to the staff, and then flies low so that Loki is dragged across the ground, along the tops of trees, and through rock-strewn gullies.

Loki screams to be released, claiming he fears his arms will be pulled from their sockets, and the eagle replies that he will comply only if Loki brings him Idunn and her magical apples that cure old age. Loki agrees and falls to the ground, afterwards returning to Odin and Hoenir to continue their journey. He says nothing to them of how he escaped from the eagle but silently begins planning how to coax Idunn from the safety of her home among the gods.

Once back in Asgard, he tells Idunn that he has found a forest with trees producing apples that look better than her own. He says he will lead her there and she should bring along her apples to compare them and she will see he is right. Idunn follows Loki to the forest where the eagle – who is actually the jötunn giant Thjazi in bird form – swoops down and carries her away to his home.

The gods do not seem to miss Idunn until they find themselves rapidly aging, becoming old and grey, and find she is gone. Gathering in conference, they realize the last time she was seen was with Loki, and they drag him before the group, promising him long torture and death if he does not return her. Loki asks Freyja for her falcon cloak that allows a wearer to fly and promises to return with Idunn.

In the form of a falcon, Loki flies to Thjazi’s home in Jotunheim and finds the giant has gone out to sea on a boat. He changes Idunn into a nut, grasps her in his claws, and swiftly flies off toward Asgard. Thjazi comes home, finds Idunn gone, and pursues in the form of an eagle. The gods, watching from Asgard’s walls, see the falcon fleeing the eagle and quickly prepare and light a pyre. The falcon swoops in low over the pyre and pulls up, but the eagle cannot stop his momentum and flies into the flames, catching fire and falling to the ground where he is killed by the gods.

Idunn is restored to her former role and the gods, presumably, eat of the apples and become young again. In the Haustlöng, there is no mention of the apples, as noted, and it seems to be Idunn’s mere presence that keeps the gods young.

Symbolism

Although Sturluson may have added the apples as a nod to the fruit in the Garden of Eden, scholars have also suggested that the addition may come from classical Greek mythology and the golden apples of the Hesperides. The Garden of the Hesperides belonged to the goddess Hera, planted with trees that produced golden apples, a gift to her from the earth goddess Gaia on her wedding to Zeus (and so associated with fertility and rejuvenation). The golden apples feature in a number of Greek myths (such as the Judgment of Paris that starts the Trojan War) but are probably best known from the Eleventh Labor of Hercules when the hero steals three from the garden.

According to this interpretation, the story of Idunn’s abduction mirrors the theft of the golden apples whose value is highlighted in the Norse tale. Scholar Rudolf Simek notes:

In the myth of the theft of Idunn, the concept of the rejuvenating applies is linked with the common tale of the theft of a goddess by a giant, and although this myth was obviously not particularly well known and might have been influenced by tales of classical mythology about Hesperides’ apples, this could have happened already long before the literary age. Perhaps it was the scholarly Icelanders of the 12th and 13th centuries who first united the classical legends with the information in the Haustlöng. (172)

Davidson also recognizes the possible connection between the golden apples of the Greeks and those of Idunn but notes that apples were already associated with fertility in Norse mythology, as were nuts, and perhaps neither were borrowed from elsewhere:

Golden apples are among the gifts offered by [the god] Freyr to Gerd in the poem Skírnismál, and refusal to take them was to mean sterility and decay. Apples were a known symbol of fertility, together with nuts and both are brought into the tale of Idunn, since Loki is said to have changed the goddess into a nut so that he could bring her back to Asgard. (175)

The Skírnismál, from the Poetic Edda, is thought to have been composed about the same time as the Haustlöng, in the 10th century, and so the concept of the apple as a symbol of fertility would have been known then. It is unclear, then, why the Haustlöng would omit the apples unless they were considered irrelevant to the nature of the goddess.

It is possible that Idunn was understood to represent the concept of hamingja, usually translated as "luck" but closer to one’s personal glory and power passed down to one’s descendants. Hamingja was personified as a powerful woman – a seeress or Valkyrie – who was the guardian spirit of a given family or of a specific member of a family. The hamingja was passed down through the generations and so symbolized continuity as well as eternity and perpetual youth. If Idunn was understood as embodying hamingja, she would have needed no apples.

Conclusion

Idunn as an embodiment of hamingja would correspond to her role as a fertility goddess in that 'fertility' was understood not only as a birthing but also any kind of rebirth. In Norse belief, nothing ever ended but died only to assume a new form. Hamingja was understood as the "good luck" or "special prowess" of one family member reborn in another of the next generation. Davidson elaborates:

In the Viking age a child would usually be named after someone in the family who had died, frequently a grandparent. This could have developed out of an assumption that the dead might in some way 'return' in his descendant, or that at least the former luck and strength which he had enjoyed might accompany the name…Such conceptions seem particularly to be associated with the fertility powers and there is a strong link between them and the burial mound. (122-123)

Davidson further notes that fertility goddesses were thought to predict the destiny of those on the cusp of adulthood, drawing on their recognition of the power the child had inherited from a deceased family member. Idunn’s power to keep the gods young and healthy may have been an illustration of this concept in that the dead never actually died as long as their hamingja was passed on to the younger generation. The deceased then became 'forever young' as long as this process continued, just as it was with the gods who, even in their death at Ragnarök, contributed to the rebirth of the Nine Realms of Norse cosmology and a new world.

In the present day, Idunn is invoked for just this kind of rebirth by Neo-Pagan and Wiccan practitioners. Supplicants may ask for help in quitting an unhealthy habit, in leaving behind a toxic relationship, or in finding their purpose and path in life. In every case, the individual is seeking a new road to follow that will reward them with the same rejuvenation Idunn offered the gods of Asgard.