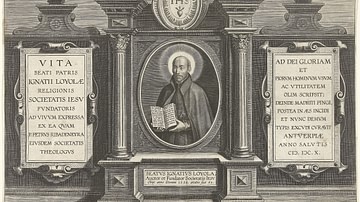

Ignatius of Loyola (l. 1491-1556) was a Basque soldier who became a Catholic priest and theologian after a mystical experience convinced him he was called to the service of Christ. He founded the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) to defend the Church and spread its message and was one of the leading figures of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

In his youth, he was significantly influenced by chivalric literature and became a courtier and soldier, serving in the army until 1521, when he was severely wounded at the Battle of Pamplona. While convalescing at his father's house, he read books on the life of Jesus Christ and the acts of the saints and became convinced he was called to serve God. After his recovery, he renounced his former life and dedicated himself to poverty and Christian service.

He devoted himself to study, prayer, and fasting, traveled to Jerusalem, and returned to study theology formally in Spain and France. At the University of Paris, he met six friends who would form the core of what would become the Jesuit order, which was approved by Pope Paul III in 1540. The Jesuit motto "Go, Set the World on Fire," coined by Loyola, was (and still is) the central directive in defending the tenets of the Catholic Church and spreading its message of universal salvation.

Loyola died in 1556 and was canonized in 1622, becoming Saint Ignatius of Loyola. Schools, colleges, universities, and seminaries around the world continue to be named in his honor as he emphasized the importance of education in furthering and defending the Catholic vision of Christianity.

Early Life

Ignatius of Loyola was born in the town of Azpeitia in the Basque territory of Spain in 1491 to noble parents of the Loyola clan and given the name Iñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola. He was the youngest of 13 children from the marriage of Don Beltrán Ibáñez de Oñaz y Loyola and Doña María Sáenz de Licona y Balda and was dedicated by his father to the priesthood when he was seven years old. Later histories of his life claim that he changed his name to Ignatius when he came to Paris, but according to scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch, the name change was the result of a scribal error when he registered at the University of Paris and was not his choice (220).

Loyola never pursued an ecclesiastical position in his youth and instead became a page boy (attendant) to a relative, Don Velázquez, who invited him to the court at Castile where he grew up to become a courtier. He learned the art of speaking diplomatically, the etiquette of high society, the use of arms, and fencing, and became known as a stylish dresser, expert dancer, and a ladies' man. He is alleged to have been involved in several duels and various crimes before and after joining the army at the age of 17.

By the time he was 18, in 1509, he was in military service to the Duke of Nájera and held the title of 'servant of the court,' which fit well with his self-image modeled after great chivalric heroes such as El Cid, King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, and tales of the knights of Castile and their great feats of arms. According to later writers, he was also influenced by the 11th-century poem The Song of Roland in which the great French knight gives his life to save his king and comrades at the Pass of Roncevaux. Loyola dreamed of becoming such a knight and attaining the same heroic immortality as El Cid or Roland.

Conversion

In 1521, however, at the Battle of Pamplona, his right leg was shattered when struck by the ricochet of a cannonball off the fortress wall, and his left leg was injured at the same time. He was cared for at Pamplona for approximately two weeks before being carried back to his father's home at Loyola. The doctors found that the bones had knit badly, and the right leg was then broken again, but when it began to heal, was deformed, and Loyola insisted on further procedures in the hope that he could be fully restored to his life at court and on the battlefield.

With the procedures done, he was put on bed rest until he could walk again and, while convalescing, asked for the kinds of books he was used to reading. Although later biographers have suggested he requested books on religion, the Autobiography of Saint Ignatius of Loyola does not support this as Loyola himself writes (referring to himself in the third person):

As Ignatius had a love for fiction, when he found himself out of danger, he asked for some romances to pass away the time. In that house there was no book of the kind. They gave him, instead, "The Life of Christ" by Rudolph, the Carthusian, and another book called the "Flowers of the Saints", both in Spanish. By frequent reading of these books, he began to get some love for spiritual things. This reading led his mind to meditate on holy things, yet sometimes it wandered to thoughts which he had been accustomed to dwell upon before. (24)

As he continued to recover, he found himself taking a greater interest in the lives of the saints than his former preoccupation with chivalric heroes. He writes:

While perusing the life of Our Lord and the saints, he began to reflect, saying to himself: "What if I should do what St. Francis did?" "What if I should act like St. Dominic?" He pondered over these things in his mind and kept continually proposing to himself serious and difficult things. He seemed to feel a certain readiness for doing them, with no other reason except this thought: "St. Dominic did this: I, too, will do it." "St. Francis did this; therefore, I will do it." (26)

He continued his reading and reflection, aware he was increasingly drawn to now emulate the lives of the saints, until his calling was confirmed for him through a vision of the Virgin Mary and Baby Jesus, who seemed to console and encourage him. He resolved to travel to Jerusalem and spend the rest of his life there in service to others as Christ and his disciples had done.

Travels & Studies

Once he could walk again, he left his father's house to begin his pilgrimage to Jerusalem. On the way, he met a Muslim, who rode with him for some time, and before leaving him, seemed to insult the Virgin Mary by suggesting that after the birth of Christ, she did not remain chaste. Loyola rode on alone but struggled between his old nature, which he felt encouraging him to follow and kill the man to defend the Virgin's honor, and his new nature calling him to prayer and forgiveness of one's enemies.

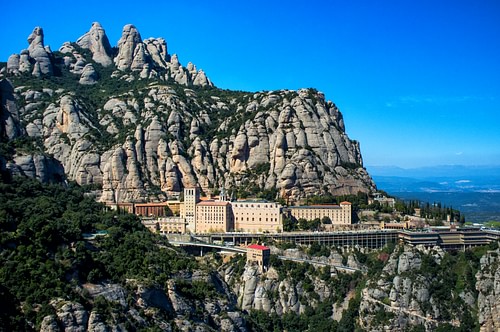

Unable to resolve this internal conflict, he left the choice up to his horse by giving it free rein; if the horse turned toward the way the Muslim had gone, he would follow, but if the horse kept to the highroad, he would continue on. He credits God with directing the horse to the highroad and bringing him to Montserrat in Catalonia, where he would declare himself a servant of Christ.

He stayed at the Benedictine Monastery in Montserrat, confessing his sins for three days and devoting himself to God's service. Remembering how his former heroes would hold vigil through the night before they were knighted, he stationed himself before the altar of the Virgin Mary, and the next morning, he hung his sword and dagger up near the altar, gave away all his fine clothes, his horse, and money, and in sackcloth, he walked to Manresa where he vowed to live the life of a Christian ascetic.

He lived at the hospital there doing chores for room and board but spent a significant amount of time in a cave, fasting and praying, where he developed the disciplines later known as Loyola's Spiritual Exercises. He would receive visions he could not at first understand but eventually concluded were Satan tempting him to abandon his present life. He felt the Virgin Mary encouraging him to take heart and continue, however, and he did so even though, at times, he found himself contemplating suicide over his struggles between doubt and faith.

In 1523, he traveled to Barcelona to embark for Jerusalem, visited Rome and Venice, and finally arrived in the Holy Land, where he had envisioned spending the rest of his life. The Franciscans, with whom he had hoped to stay, had no room for him, however, and could not guarantee his safety there. He was told to return home, and after he had visited the Mount of Olives and other sites, he took ship to Cyprus and then back to Venice. He traveled through Italy and Spain on foot, was arrested as a spy and released, was interrogated by the Inquisition for public preaching when he was not a priest, and finally arrived back in Barcelona, where he enrolled in the university.

In 1534, after completing his studies in Latin and theology, he enrolled at the University of Paris and came to be known as Ignatius instead of Iñigo. In the course of his studies, he met the six men who would form the basis for his order of the Society of Jesus:

- Nicholas Bobadilla

- Peter Faber

- Diego Laynez

- Simão Rodrigues

- Alfonso Salmeron

- Francis Xavier

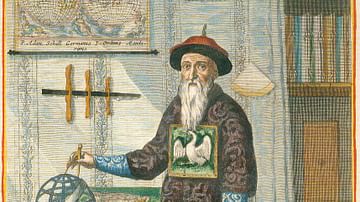

Francis Xavier (l. 1506-1552, later Saint Francis Xavier) would become as well-known as Loyola himself for his missionary activities in the Far East. The six committed themselves to the vision Loyola had of a 'secular order' of priests who would spread the Catholic message and defend the faith in Jerusalem, but if that were not possible, they would perform whatever good they could for the pope and Church. By this time, Loyola had developed his personal spiritual exercises into a discipline for others which his six friends submitted to.

The Spiritual Exercises

Loyola's exercises were a four-week course of spiritual discipline to ready oneself for complete devotion to the service of God. Loyola defines the purpose of the course in the introduction to his manual Spiritual Exercises (1548):

By the term "Spiritual Exercises" is meant every method of examination of conscience, of meditation, of contemplation, of vocal and mental prayer, and of other spiritual activities that will be mentioned later. For just as taking a walk, journeying on foot, and running are bodily exercises, so we call spiritual exercises every way of preparing and disposing the soul to rid itself of all inordinate attachments, and, after their removal, of seeking and finding the will of God in the disposition of our life for the salvation of our soul. (Janz, 427)

As noted, the exercises were first developed by Loyola for himself in the cave at Manresa, but he had since refined them as a course for others after experiencing their benefits. Loyola made the exercises mandatory for his six friends and, later, for anyone wishing to join the Jesuit order, writing them out and publishing them in 1548. MacCulloch notes:

[The Spiritual Exercises] has become one of the most influential books in the history of the Western Church, even though Ignatius did not design it for reading any more than one would a technical manual of engineering or computing. It is there to be used by clerical spiritual directors guiding others as Ignatius did himself, to be adapted at whatever level might be appropriate for the situation of those who sought to benefit from it, in what came to be known as "making the Exercises." (221)

The exercises focused on gratitude for the gifts of God expressed in praise and a denial of one's self-interest. As one centered one's mind on the greatness of God, the individual self would give place to the Holy Spirit, encouraging a selfless devotion to the good of others. Loyola encouraged suspending the tendency to judge others, praise for the tenets of the Church and its policies, positive thinking and the acts which proceeded from a grateful heart, and an unquestioning trust and loyalty in church teachings. In one of the most famous passages from the work, he writes:

If we wish to proceed securely in all things, we must hold fast to the following principle: What seems to me white, I will believe black if the hierarchical church so defines. For I must be convinced that in Christ our Lord, the bridegroom, and in his spouse the church, only one Spirit holds sway, which governs and rules for the salvation of souls. (Point 13, Janz, 429)

After Loyola's six friends had completed the exercises, they resolved to travel to Jerusalem and realize his earlier vision of serving others there in imitation of Christ and his disciples. They traveled to Venice to book passage in 1537, but the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor had declared war on the Turks of the Ottoman Empire, and all travel to the Holy Land was banned. Loyola had once left the course of his life up to his horse but long since had come to trust in God to direct his path. He and the others concluded God had other plans for them, and since they could not minister in Jerusalem, they would offer their services to the pope.

The Society of Jesus

Pope Paul III (served 1534-1549) approved the Society of Jesus in 1540, and Loyola became the first Superior General (official leader) of the Jesuits. The order was far from an instant success, however, due to a lack of focus and the hostility of established orders such as the Theatines (also known as the Congregation of Clerics Regular), who were already doing what the Jesuits proposed in outreach/evangelism to non-Catholics, reformation and education of the clergy, and ministry to the poor. The Spanish Inquisition, which had interrogated Loyola years before, was also suspicious of the new order, as it knew Loyola accepted mystical visions as authentic revelations from God – a claim the Inquisition had crushed earlier in dealing with the Spanish reformed group known as the alumbrados with whom they associated Loyola.

The Theatines, Franciscans, Dominicans, and others condemned the Jesuits for what today would be called 'duplication of services,' but Loyola was able to differentiate his order from the others through his Spiritual Exercises, which inspired zeal and encouraged focus in adherents. Within 25 years of their founding, the Jesuits claimed 3,000 members who had established themselves on three continents, raised universities, colleges, and seminaries, and converted thousands to Catholicism, while also defending the Church against the criticisms brought by the Protestant Reformation.

Conclusion

The Jesuits were central to the efforts of the Catholic Counter-Reformation in producing highly-educated, multilingual priests who could preach in countries as diverse as Germany or Japan. After The Council of Trent (1545-1563), which condemned the Protestant Reformation as heresy, they refuted Protestant claims and theological arguments through logic and recourse to classical literature (specifically the philosophical skepticism of Sextus Empiricus) as well as the traditions and authority of the Church. Scholar Philip M. Soergel notes:

[The Jesuits would] have the most far-reaching effects in the Catholic world in the years to come…[Their] "Letters from the Far East," dispatches the society's missionaries sent home, which were translated into many European languages and published in urban centers throughout the Continent, filled with tales of conversions, spiritual feats, and wonders the Jesuits had worked in Japan and China, became widely consumed propaganda for the Roman Church's late sixteenth-century renewal. (Rublack, 255)

Ignatius Loyola died on 31 July 1556 of malaria and was interred in the crypt of the Maria della Strada Church in Rome. He was beatified in 1609 and canonized in 1622, by which time his name had become as well-known as any of the chivalric heroes he had admired in his youth.