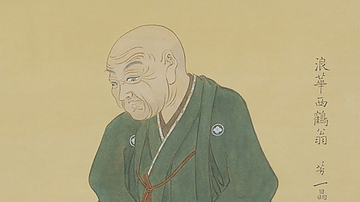

Ihara Saikaku (1642-1693) was a Japanese poet and novelist who played a leading role in creating the so-called ‘floating world’ (ukiyo-zoshi) genre of popular literature in the 17th century. His work was significant because, in terms of both production and content, it reflected the rise of a commercial economy and a new urban class in the early modern period in Japan.

Osaka – Merchants’ Capital of Japan

After the coming of peace to Japan in the early 17th century, agricultural output increased and the population expanded. This led to the growth of towns and cities at both a local and national level. Before 1600, the capital of Kyoto was the only large city in Japan but in the 17th century, both Edo and Osaka also became large cities. Edo was located in eastern Japan and it was the seat of government for the Tokugawa so it had a large warrior population. In western Japan, Osaka developed as a new commercial city. Although the Tokugawa rebuilt Osaka Castle in the 1620s and stationed a garrison there, the number of warriors in the city was relatively small compared to that of merchants. At the time, tax was collected in rice and the ruling warrior elite also received their stipends in rice so it was an important commodity, not just for food, but also for trade. In addition, products such as cotton, silk, paper, wax, and salt were produced and traded through the port of Osaka. New shipping routes connecting Osaka with the towns along the coast in western Japan were also opened. This made the city a hive of commercial activity and a new kind of urban culture developed there that reflected the interests of the city’s residents. This was most vividly expressed in two new forms of theatre, the puppet play and kabuki, in which writers like Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724) presented dramas to entertain the townsfolk. It can also be seen in the growth of book publishing.

Rise of Commercial Publishing

Before the 17th century, literacy in Japan was restricted to a very small number of court aristocrats, high-ranking warriors, and Buddhist priests. The growth of towns and cities in the early Edo period, however, facilitated the spread of literacy. In the local castle towns, many daimyo established schools for the sons of their warrior retainers so that they could acquire the skills necessary to carry out the administrative tasks the new age required. The children of commoners could also get an education through private temple schools called terakoya. The spread of literacy was greatly enhanced by the rise of commercial publishing which made books much more readily available.

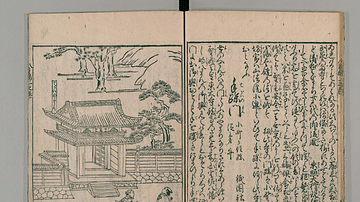

Printing with woodblock prints had been introduced to Japan from China in the 8th century but its use had largely been restricted to the reproduction of Buddhist texts. Books mostly circulated in manuscript form. In the 16th century, printing with movable type entered Japan from both Korea and Europe. In Europe, this new technology had a revolutionary impact but in Japan it was quickly abandoned. This was because it was not well suited to printing the Japanese script that consists of two kana alphabets and thousands of Chinese characters. To print books, especially in the cursive kana style, it was much easier to etch the text into a wood block and then use that to print books. Using this method also meant that it was easy to include illustrations with the text. The main difficulty with this kind of printing was that the blocks would wear out after a time and had to be remade. This was not especially problematic as book runs were small and labour was cheap. As a consequence, from the 17th century, books were mass-produced in Japan. The first books to be written in this style were called ‘kana zoshi’ which means ‘books written in kana’, kana being the phonetic scripts used to write in Japanese. These were printed in very small quantities, mainly in Kyoto and on a diverse range of topics. They are regarded as important because they were the precursor of ‘ukiyo zoshi’, ‘books from the floating world’ that Saikaku popularised.

Saikaku’s Early Years

Little is known about Saikaku’s early life apart from the fact that he was born into a rich merchant family in Osaka. His real name was Hirayama Togo. Ihara Saikaku was one of several pen names he used later in life. He was a skilled poet and worked as an amateur instructor from his early twenties. His wife died when he was 33 leaving him with three children to look after, including a blind daughter. The death of his wife inspired him to create one of his most personal works, Dokugin ichinichi senku ('A Thousand Verses Composed Alone in a Single Day', 1675). After his wife’s death, he turned over the running of the family business to a steward and devoted himself to travel and writing. Over the next decade, he became a very successful poet famed for his ability to compose very large numbers of poems in the poetry competitions that were popular at the time. In this regard, Saikaku’s career stands in marked contrast to his contemporary Matsuo Basho (1644-94), whose poetry is known for its introspection and philosophical insights.

Saikaku’s First Novel - ‘The Man Who Loved Love’

In 1682, Saikaku wrote a collection of fictional stories called Koshoku ichidai otoko ('The Man who Loved Love'). Contrary to his expectation, this sold out quickly and went through a further three pressings. The rights to the book were then sold to a more established publisher who also produced a further three editions. In 1684, a publisher in Edo came out with a deluxe illustrated edition that went through three more editions. As Paul Schalow has written, “The book would change both Saikaku’s career and the history of Japanese literature.”

'The Man Who Loves Love' is loosely modelled on the Heian period classic The Tale of Genji and is a collection of 54 stories that describe the sexual exploits of its main character, Yonosuke. At the time, popular literature tended to simply retell stories from the classics but in his stories, Saikaku portrayed contemporary life in a way that was new and captured the popular imagination. It was full of humorous twists and turns of fate that made the story appealing and was also written in stylish prose that was influenced by his poetry. Following the success of this book, Saikaku devoted the rest of his life to writing works in a similar style.

This genre is called ukiyo-zoshi, ‘books of the floating world’. ‘Ukiyo’ was originally a Buddhist concept that referred to the transient nature of human existence. In the 17th century, however, it came to mean the transient nature of human pleasure and referred to the kind of entertainment enjoyed by some of the residents in Japan’s biggest cities. Illustrations were an important element in ukiyo-zoshi. The inclusion of these not only entertained contemporary readers but also provides modern-day ones with some idea of what 17th century Japan looked like. Some of Saikaku’s books were illustrated by Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–94), one of the most famous artists of the day. Later he developed ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) into a separate art form known in English as woodblock prints.

In addition to their literary merit, Saikaku’s books are of interest because, through them, we can learn about life in the Edo period. Quite a few of his books have been translated into English and this makes them accessible to a modern audience. Of course, they are not sociology textbooks and the content cannot be taken at face value. They were intended as entertainment and much of the humour is derived from exaggeration and parody. Still, his writing about love, merchant life and warriors provide insights in to everyday life that we cannot find in other sources.

The Books about Love

Following the success of 'A Man Who Loved Love', Saikaku wrote another eleven books on similar themes. These included Shoen o kagami ('The Great Mirror of Beauties', more commonly called 'Another Man who Loved Love', 1684); Wankyu isse no monogatari ('The Tale of Wankyu', 1685); Koshoku gonin onna ('Five Women Who Loved Love', 1686), Koshoku ichidai onna ('The Woman Who Loved Love', 1686) and Nanshoku o kagami ('The Great Mirror of Male Love', 1687). Although the word ‘love’ is used in the translated titles of Saikaku’s work, a more accurate, but less poetic, translation might be ‘recreational sex’, that is, sexual enjoyment without any emotional commitment.

Saikaku repeatedly points out both the good and bad points of such activity. For example, The Tale of Wankyu is an account of the life of an Osaka merchant. It describes his extravagant spending in pursuit of courtesans in the pleasure quarters and ends in his bankruptcy and death by drowning. Five Women Who Loved Love contains five short stories about different women who break the law in order to be with the man they love. Four of the women die as a result, while the fifth receives an inheritance that allows her and her lover to live out their lives in luxury. The Woman Who Loved Love describes the downward spiral of a beautiful woman who was a top-ranked courtesan in the pleasure quarters in her youth but ends up as a common prostitute in her old age. Although the stories are rather exaggerated, they provide us with some understanding of social values at the time.

In the Edo period, prostitution was commonplace and it can be seen as one of the less pleasant aspects of the rise of a commercial economy. In an attempt to maintain social order, however, the government tried to restrict it to licensed areas usually referred to in English as ‘pleasure quarters’. The most famous of these were the Yoshiwara area in Edo, the Shimbara area in Kyoto, and the Shinmachi area in Osaka. The top courtesans had a cultural influence like famous Hollywood actresses in our own day in terms of setting fashion trends and notoriety. For those of lower rank, however, the life was one of terrible hardship. Girls were often sold into prostitution like indentured servants by their parents and they would have to work in the brothels until either their debts were paid off or they died.

The Books about Merchants & Warriors

In contrast to his 12 books on love, Saikaku only wrote three books each about the life of merchants and the life of warriors.

The books about merchants were: Nippon eitaigura, ('The Eternal Storehouse of Japan', 1688) and Seken munesan'yo, ('This Scheming World', 1692) and Saikaku oridome ('Saikaku’s Final Weaving', 1694), which was published after his death. As with his books about love, Saikaku sends mixed messages about the morality of doing business. At the beginning of the Eternal Storehouse of Japan, for example, he claims it is a book about how to become wealthy in the new economic environment. Many of the stories, however, are critical of valuing money above all else and praise the values of simplicity, thrift, and hard work. This Scheming World is a collection of stories about the difficulty middle- and lower-level townspeople had in paying off debt. In the 17th century, it had become the custom that debts had to be paid off by certain days. Of these, the last day of the year was most important and Saikaku describes the lengths people went to, to either pay or avoid paying, their creditors.

The books about warriors were Budo denrai ki ('A Record of the Transmission of the Way of the Warrior', 1687), Buke giri monogatari ('Tales of Samurai Honour', 1688) and Shin kashoki ('The New Kashoki', 1688). Saikaku was writing at a time when the warrior class was undergoing a great transformation. Before 1600 they had been actual fighters but with the coming of peace, there were no more wars to fight. As they turned into a class of civil administrators, their martial skills were no longer required. With the spread of Confucian ideas to Japan, abstract concepts such as ‘loyalty’, ‘duty’, and ‘filial piety’ came to replace the more practical considerations that were important on the battlefield. With the rise in popularity of the puppet theatre and kabuki, warrior heroics came to be something that could only be seen in historical dramas on the stage. These heroes of old seem to stand in stark contrast with the increasingly impoverished warriors of the present day.

Saikaku’s books about warriors reflect this ambiguity. A Record of the Transmission of the Martial Arts, for example, was a collection of stories about vendettas that portrayed warriors as brutal killers. In contrast, the stories in Tales of Samurai Honour show them behaving in a more ethical, although often self-serving, way. Given Saikaku’s writing style and his use of parody, it is hard to tell whether he is praising warriors or mocking them.

Saikaku’s Place in Japanese Literary History

Saikaku died in Osaka in 1693. Along with the dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon and the poet Matsuo Basho, he is regarded as one of the three great literary figures of the Edo period. Historians commonly use the term ‘early modern’ to describe the Edo period. The use of this term indicates that there was a break with the preceding ‘medieval’ era and some continuity with the succeeding ‘modern’ one. This can be seen in Saikaku’s life and work. Although his writing was part of a long Japanese literary tradition, he was the first person to write books that, not only featured ordinary people as their subject matter, but were also written for them. In this regard, he can be regarded as one of the founders of Japanese popular culture that has now become well-known around the world.