The Indian Massacre of 1622 was an attack on the settlements of the Virginia Colony by the tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy under their leader Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646) and his brother Opitchapam (d. c. 1630) resulting in the deaths of 347 colonists. Credit for its success is always given to Opchanacanough with Opitchapam playing a secondary role.

The attack was carefully planned and carried out with such speed and precision that only one settlement, Jamestown, received warning and was able to prepare a defense. Out of approximately 1,250 English colonists, 347 were killed on 22 March 1622, mostly before noon, and hundreds more would die in the following months from malnutrition, starvation, and disease due to the destruction of their crops as well as further periodic engagements with natives.

The attack was a complete surprise and total military victory for the Powhatan Confederacy. Peace had been established between the colonists and natives since the end of the First Powhatan War in 1614. Natives and colonists partnered in trade, visited each other’s settlements, and natives were often guests in colonist’s homes. Since 1610, however, the colonists had begun to spread out from their initial settlement at Jamestown, taking more and more lands from the Powhatan Confederacy, abusing the people, stealing food, and allowing livestock to destroy crops and desecrate sites sacred to native rituals. Opchanacanough’s attack had three objectives:

- Demonstrate the military might of the Powhatan Confederacy

- Demoralize the English colonists

- Encourage them to pack up and return to their own country

The attack succeeded in the first two objectives but, instead of leaving, the colonists entrenched and fought back in the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626) which they won. Afterwards, trade with certain tribes was discouraged and more land was taken for tobacco plantations. Opchanacanough launched another offensive in 1644, setting off the Third Powhatan War (1644-1646) which ended when he was taken captive and killed.

Following this conflict, the Treaty of 1646 dissolved the Powhatan Confederacy and led to the reservation system for Native American tribes in the area. The 1622 massacre also influenced Anglo-Native relations elsewhere in the English colonies, contributing to English policies and military campaigns during the Pequot War (1636-1638) and King Philip’s War (1675-1678) in New England and the development of laws concerning Native Americans afterwards.

Jamestown & Powhatan Confederacy

The Jamestown Colony of Virginia was established by the English in 1607 and fairly quickly came into conflict with the native tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy. These tribes had lived on the land which they knew as Tsenacommacah (“densely populated land”) for thousands of years, establishing cultural traditions linked to the area. The Spanish arrived in the West Indies in 1492 and then colonized South and Central America, extending their reach up through the modern-day State of Florida and laying further claim to the North American east coast up to present-day New York State. They had not colonized above Florida, however, and limited themselves to raids along the coast, kidnapping natives to sell into slavery.

The English, who were late in their colonization efforts in the so-called New World, established their Roanoke Colony in 1585 and again in 1587 in Virginia, but it did not survive past 1590. The natives, therefore, were already acquainted with Europeans by 1607 and the experiences had been far from pleasant. The Powhatan Confederacy, led by Chief Powhatan (also known as Wahunsenacah, l. c. 1547 - c. 1618), did not mind the English at first because they had chosen a swamp of unusable land for their settlement and, further, thought the English might serve as allies against the Spanish and other hostile tribes. Chief Powhatan, therefore, ordered his people to supply the ill-equipped and inept colonists with food and supplies.

The colonists came to expect this type of service rather than learning to fend for themselves. Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) established a good working relationship with Chief Powhatan in 1607 but, by 1609, this was strained by the colonists' continued abuse of the natives through theft of land and food. Smith himself, in spite of his earlier efforts to befriend the tribes, eventually participated in food theft himself and left the colony for England in October 1609 without informing Chief Powhatan of his departure.

After Smith was gone, the colonists took more food and occupied more land outside of Jamestown as they considered the natives to be subjects of the English king as they were themselves. These actions led Chief Powhatan to order them inside their settlement and to give his warriors leave to kill anyone found outside the fortifications. Powhatan’s decree contributed to what is known as the Starving Time in Jamestown’s history during which over 80% of the colonists died.

In May of 1610, a new governor, Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622) arrived and, shortly after him, the aristocrat Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618). West rejected Smith’s earlier approach in dealing with the natives and instituted a policy of no compromise which set off the First Powhatan War (1610-1614), a series of guerilla strikes and counterstrikes killing many on both sides.

Peace of Pocahontas

The natives were better guerilla fighters and their weapons of the bow and arrow more effective than the colonists’ muskets which took more time to reload than it took a native archer to notch another arrow. The colonists, however, had a seemingly infinite supply of people who kept arriving to replace those who had been killed while the tribes of the confederacy lacked this luxury. The colonists also continually displaced the natives by attacking a village, killing the people, and fortifying it, thereby depriving native populations of land and resources they were using in the war and enlarging the buffer zone between English settlements and native villages.

While the war raged on, more and more colonists arrived with more muskets and cannons, and settlements were established further inland. One of the colonists who had arrived in May of 1610 with Gates was John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622), who came with some hybrid tobacco seeds which he experimented with and planted. His tobacco became the most lucrative cash crop of the colony, and by 1614, he was a wealthy man with a large plantation across the river from the Henricus Colony, north of Jamestown. West fell ill in 1613 and returned to England after turning his authority over to Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626), who continued his policies. That same year, Argall kidnapped Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617), daughter of Chief Powhatan, holding her for ransom at Henricus.

Chief Powhatan agreed to the terms of her release and sent Argall the tools, weapons, and prisoners requested, but Argall claimed he had not honored the deal and kept Pocahontas. She converted to Christianity, taking the name Rebecca, and married John Rolfe in April 1614. Chief Powhatan and the colonial authorities both approved of the union and so ended the First Powhatan War. The eight years that followed became known as the Peace of Pocahontas during which trade between the colonists and natives flourished and land transactions were, for the most part, approved by both sides.

Lead-up to the Massacre

Pocahontas, Rolfe, and their young son, Thomas Rolfe (l. 1615 - c. 1680) left for England on a promotional tour to generate further investment in the colony in 1616. Pocahontas died in 1617 as they were on their way back to Virginia, and Thomas was left in the care of Rolfe’s brother in England. Chief Powhatan kept the peace in honor of his grandson but stepped down as chief shortly after his daughter’s death. His brother, Opitchapam then became chief, but he was not as powerful or popular among the tribes as Chief Powhatan’s half-brother, Opchanacanough. Opchanacanough became Chief Powhatan, and Wahunsenacah died shortly afterwards, sometime in 1618.

When Pocahontas had gone to England, Wahunsenacah had sent along a number of her family and tribal members including her brother-in-law Tomocomo who was also one of his sages and counselors. Tomocomo was to observe the English in their own land and return with a report. According to colonial English accounts, Tomocomo criticized the English harshly before a council of the elders and chiefs but was shamed into silence by a colonial delegation which countered his claims that the English could not be trusted. These accounts are suspect, however, as they were written by colonists – who, in fact, could not be trusted – justifying later atrocities committed against the natives.

Opchanacanough seems to have accepted Tomocomo’s words as truth and planned accordingly. The Peace of Pocahontas still held in 1619 and the trade agreements had encouraged friendly relations between the immigrants and the indigenous tribes. In 1611, when Henricus had been established by Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560-1619), the first college in North America was founded close by for the purpose of educating Native American youth in Christianity and European culture. Pocahontas’ conversion had encouraged the hope that more natives would follow her example and more effort was put into evangelizing the natives.

Opchanacanough took advantage of these efforts, encouraging his people to show more interest in conversion – and he led by example in doing so himself – which led the colonists to believe further in the peaceful intentions of the tribes. The Records of the Virginia Company (the group who had funded the 1607 Jamestown expedition and still controlled the colony) make clear that, in 1621, relations between colonists and natives were considered better than ever. The report, written after the massacre, describes the period leading up to it:

[Word was received from Opchanacanough] that he held the peace concluded so firm as the sky should sooner fall than it dissolve. Yea, such was the treacherous dissimulation of that people who then had contrived our destruction, that even two days before the massacre, some of our men were guided through the woods by them in safety…and many the like passages, rather increasing our former confidence than in any wise ministering the least suspicion of the breach of the peace or of what instantly ensued; Yea, they borrowed our own boats to convey themselves across the river to consult of the devilish murder that ensued and of our utter extirpation, which God of his mercy prevented. (550)

John Rolfe had remarried by this time and was back at his plantation, making regular trips across the river to Henricus. The House of Burgesses, first established in 1619, had made it their first order of business to address a wrong committed against Native Americans by a wealthy landowner. In 1621, Opchanacanough’s war chief, Nemattanew (d. 1621) was killed by the colonists after he was accused of killing one of their own and taking his clothes. Opchanacanough took no action, claiming his man had been justly killed (though whether he meant this is debated), and letting the event go.

The Massacre

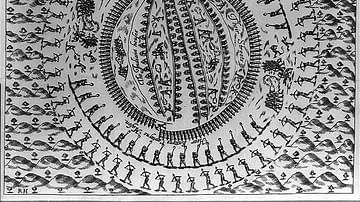

At about that same time, he and his brother Opitchapam took “war names” in preparation for the attack and called on the tribes to participate in a ceremony honoring the life of Wahunsenacah. This event stirred no suspicion among the colonists at the time but, later, they came to believe this was a pretense under which Chief Powhatan was able to bring all the tribal chiefs together to coordinate the assault. At this time, it was later surmised, the natives gathered intelligence on where certain colonists would be in various settlements, who would be working in the fields at what time, how long the full-scale attack would take to complete, etc.

The morning of 22 March 1622, Good Friday, began as any other with the colonists going to work on their farms and in their shops. Scholar Charles C. Mann describes the events which followed:

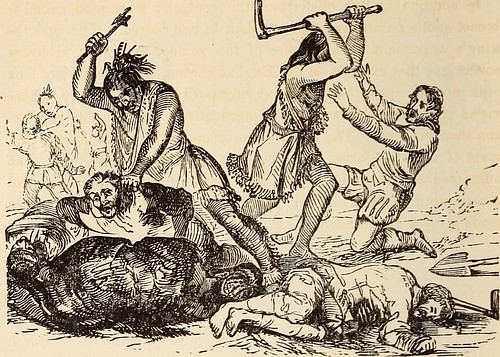

Early that morning, Indians slipped into European settlements, knocking on doors and asking to be let in. Most were familiar visitors. They came unarmed. Many accepted a meal or a drink. Then they seized whatever implement came to hand – kitchen knife, heavy stewpot, the colonists’ own guns – and killed everyone in the house. The assault was brutal, widespread, and well planned. So swift were the blows that many colonists died without knowing they were under attack. Entire families fell. Houses burned across what had been Tsenacomoco. At the last minute, several Indians told English friends about the attack, providing enough warning to let Jamestown gather its defenses. Nonetheless, the attackers killed at least 325 people. (89)

The number killed is hard to determine but is usually given as 347. The college, hospital, and colony of Henricus were completely destroyed, and all the inhabitants killed (including, presumably, John Rolfe). Settlements burned all across the region, and the surviving colonists were stunned into inaction. They had grown used to small conflicts breaking out which were quickly resolved; none of them could conceive of what they had just experienced.

Aftermath & Response

At this point, Opchanacanough could have easily finished the survivors off. Those outside of Jamestown would have been easy enough to kill as they had no defenses, and Jamestown could have been set on fire with fleeing colonists then killed as they tried to escape; instead, he did nothing but wait for a response. It was his hope that this response would take the form of the colonists’ swift departure from his lands – which he believed was what a Native American tribe would do – but he had misjudged his opponent.

The colonists began to regroup and rebuild and traded again with the tribes that had attacked them. They actually had little choice, however, as their own crops had been burned. Mann comments:

The aftermath [of the massacre] claimed as many as seven hundred more lives. Because the attack disrupted spring planting, the [colonists] grew even less maize than usual. Meanwhile the [Virginia Company] tried to rebuild Jamestown by sending over a thousand new colonists. Incredibly, they came to Virginia with no food supplies. (90)

Reinforcements could not help against the guerilla tactics of the natives in the Second Powhatan War, however, and so the colonists resorted to trickery. They called for a peace conference at which they poisoned the wine and, once the chiefs had fallen, attacked their bodyguards and attendants, killing over 200 of them. The war continued until Opchanacanough sued for peace in 1626, but hostilities went on through 1629 and into the 1630s in some areas.

Conclusion

News of the massacre had reached England by June of 1622 and King James I of England (r. 1603-1625) was outraged. He dissolved the Virginia Company and took direct control of the colony through a Royal Charter, claiming he was better able to protect the colonists than the company had been. Whether James I actually meant this is unknown; it is just as likely he wanted direct control of the profitable tobacco exports from the colonies.

On 22 March 1624, the House of Burgesses convened and passed the decree that 22 March be solemnized as a holiday to commemorate the massacre. In making the date a solemn holiday – during which the events of the massacre would be recounted – the colonists ensured that new arrivals would experience it through first-hand accounts of those who had lived it and then through stories based on those accounts. The animosity between the colonists and the indigenous tribes worsened as the stories of the Massacre of 1622 were told and retold. These accounts were added to after Opchanacanough launched another attack in 1644, killing over 500 colonists, and starting the Third Powhatan War. This conflict ended in 1646 with the capture of the chief and his assassination by a prison guard who shot him in the back.

When the Pequot War broke out in New England in 1636 or King Philip’s War in 1675, the savagery of the colonists’ attacks was informed, in part, by the stories of the Indian Massacre at Virginia of 1622. The natives were considered dangerous and untrustworthy, capable of vast levels of deception, and eager to kill defenseless English men, women, and children. Actually, the natives had only learned from the English how to hone their arts of deception and trickery.

The massacre of 1622 was not, as the colonists characterized it, the act of "ungrateful savages" who had only benefited from Christian kindness and English courtesy; it was a carefully planned and executed response to years of abuse and theft by self-righteous, land-greedy, racist English colonists who cared nothing for the souls of the natives they claimed to pray for and, by their own accounts, considered them barely human. By 1622, the colonists had already committed enough atrocities against the natives to warrant such a response. By the end of the 17th century, they had committed even more but, still, justified their theft of even more Native American land and the slaughter of indigenous tribes by invoking the Indian Massacre of 1622.