The Investiture Controversy, also referred to as the Investiture Contest or Investiture Dispute, was a conflict lasting from 1076 to 1122 between the papacy of the Catholic Church and the Salian Dynasty of German monarchs who ruled the Holy Roman Empire. The papal-imperial conflict was focused on the appointment of bishops, priests, and monastic officials through the practice of lay investiture, in which these church officials were selected for their positions and installed through the exchange of the vestments and physical symbols of the respective offices by secular rulers rather than by the pope. The dispute was largely an ideological one between the coalitions of Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073-1085) and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1084-1105) and the King of the Germans (r. 1056-1105), although the conflict persisted beyond their deaths and had political ramifications for centuries to come.

The investiture dispute grew gradually in the 11th century from minor interventions of the imperial lords in church affairs and from a sweeping reform movement within the medieval church helmed by the popes, in which the reform goal was "...the complete freedom of the church from control by the state, the negation of the sacramental character of kingship, and the domination of the papacy over secular rulers…" (Cantor, 245). These developments occurred simultaneously and were not necessarily antagonistic until after the death of Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1046-1056). Tension from the clash of secular and religious authority reached its tipping point in 1076 when Henry IV called for the abdication of Gregory VII, who subsequently excommunicated the monarch. Civil war broke out soon after between the imperial loyalists of Henry IV and a coalition of anti-imperialists and Gregorian reformers.

While open conflict slowed by the end of the century, the equilibrium of European politics had been disrupted. The complex conflict of religious, imperial, and local authority persisted into the 12th century and was settled in 1122 by the Concordat of Worms. This compromise between Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1106-1125) and Pope Callixtus II (r. 1119-1124) distinguished the unique roles of secular rulers and church officials in the selection and investiture process, restructuring the relationship between the Church and the Empire, as well as secular governments in general. Conflict over the authorities of church and state did not cease in 1122, but the Concordat limited the secular influence over the papacy after several centuries and temporarily quashed the idea of a theocratic Holy Roman Empire.

Background

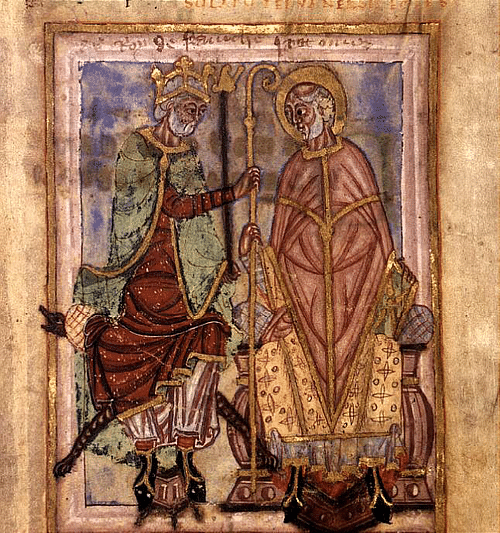

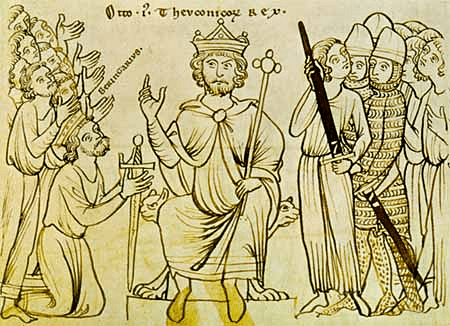

The reign of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 962-973) of the Germanic Ottonian Dynasty was saturated with religious patronage to promote his influence over the church and became referred to as the Ottonian Renaissance. Shortly after his coronation, he began restructuring the relationship between the secular kingdoms and the papacy, claiming his right to create new fiefdoms within the empire’s territory and to install handpicked lords or bishops to manage those lands. Otto’s religious patronage included "endowments to the German bishoprics, monasteries, and convents...the foundation of cathedral schools and the production of new editions of classical texts… as well as a wealth of new liturgical literature," religious poems and plays, regional and cultural histories, and a variety of other texts (Whaley, 27-28).

Beyond these activities, Otto I and his imperial successors consolidated their control by intervening further in local church affairs through lay investiture. By appointing personal or political associates to positions of religious authority, primarily as bishops and abbots, the secular rulers established their direct control over those ecclesiastical offices and the property attached to them, including churches, cathedrals, convents, monasteries, and any associated estates. The selection and appointment processes of lay investiture maintained by the Ottonian and Salian dynasties superseded the right of popes and archbishops to do the same, reinforcing the superiority of secular rulers over the church and papacy.

Holy Roman Emperor Henry III, the second Salian emperor, was particularly noted for his public displays of religiosity and piety, as well as his intervention in church affairs. Most notably in 1046, he appointed the bishops of Aquileia, Milan, and Ravenna in Italy to their positions and, at the Synod of Sutri, ended a papal dispute between three rival papal claimants by deposing them and selecting Bishop Suidger of Bamberg to be installed as Pope Clement II (r. 1046-1047). The three consecutive successors to Clement II - Damasus II, Leo IX, and Victor II - were also selected by Henry III from a pool of loyal German bishops and were the heads of the church until 1057. By the time Henry III died in 1056, de facto supremacy of the Holy Roman Empire over the church and papacy was undeniable due to the secular influence of the church’s highest office.

11th-century Papal Reform

In the early 11th century, a clerical and monastic reform movement emerged within the church. Led by the papacy and supported by prominent church figures, including Peter Damian, Hugh of Cluny, and Anselm of Lucca, the reform policies were focused on the idea of church independence from secular interference and papal superiority over lay rulers. The papal claims of secular authority over monarchs and lords were derived in part from the fraudulent Donation of Constantine, a forged document claimed to record the 4th-century grant of all Western Roman Empire lands and holdings to the papacy by Roman Emperor Constantine I (306-337 CE). The church and its adherents, according to the reformers, became oppressed by the German kings and emperors since the time of Constantine as they institutionalized their control over ecclesiastical property and offices.

Church reformers targeted investiture and related secular interferences. In particular, the practice of simony and the marriage of the clergy, already prohibited by church canon, were seen as the key issues needing resolution. Both clerical marriage and simony, the sale of ecclesiastical positions, were criticized as causes of immorality within the church. Simony was a common practice in medieval European feudalism in which newly invested church officials repaid their appointer for the position. The transaction went beyond the appointment procedure established by church law. As a result of this subversion, simony was heavily rallied against in the mid-11th century by Clement II and Leo IX (r. 1049-1054) as the central cause of secular corruption of the church.

The 11th-century popes, including those appointed by Henry III, structured the reform movement around independence and supported their goals by developing the church’s canon law. In addition to the campaigns against simony and clerical marriage, Pope Leo IX actively guided the codification of canon law, papal decrees, and Scripture. He styled the papacy as the sole judge on Christian doctrine and ritual in pursuit of universalism and Roman dominance of Christianity. These actions aggravated tensions with the Byzantine Empire and in part brought on Christianity’s East-West Schism of 1054, separating the Roman and Byzantine churches into independent institutions. In response to Henry III’s installation of popes during his imperial reign, Pope Nicholas II (r. 1058-1061), another ardent reformer, issued a papal bull in 1059, outlawing secular interference in the appointment of popes by assigning the authority of papal selection exclusively to an electoral assembly of seven bishops, which later became the College of Cardinals.

Gregory VII & Henry IV

The papal reform movement surged following the installation of Hildebrand of Sovana as Pope Gregory VII. An ardent defender of church authority over secular powers throughout his life, Gregory continued his unrelenting pursuit of reform and papal superiority as the leader of the church. His policies, which became known as the eponymous Gregorian Reforms, stemmed from those of his reform-minded predecessors and were supported by members of the clergy and laity alike who opposed the "domination of the church by laymen and the involvement of the church in feudal obligations" (Cantor, 244).

Gregory and his supporters were especially concerned with lay investiture, and their challenges to its practice increased the papal-imperial tension. In 1074, Gregory VII, uncompromising in his claims of church supremacy over the secular world, asserted that church officials could only be installed by the pope and demanded that secular rulers obey this policy. The following year, Gregory wrote his Dictatus Papae, a list of 27 statements defining the powers of the papacy. Peter Wilson concisely summarized Gregory’s declarations: the church’s "immortal soul was superior to the mortal body of the state. The pope was supreme over both, entitled to reject bishops and kings if they were unfit for office" (55).

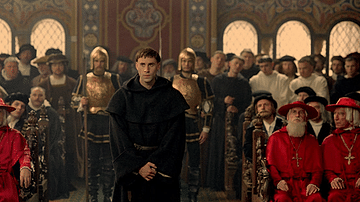

Gregory’s assertions of papal superiority went ignored by Henry IV, the young heir to Henry III. Once his regency was dissolved in 1065, Henry IV faced constant challenges and local revolts, most notably in Saxony and northern Italy, against his attempts at creating a stronger centralized monarchy. A common practitioner of investiture, simony, and political patronage, Henry ignited the papal-imperial tension when he installed new archbishops in Fermo, Milan, and Spoleto in 1075, to which Gregory responded by threatening excommunication. Undaunted and familiar with challenges to his kingship, Henry assembled imperial-supporting bishops and clergymen at the Synod of Worms in January 1076. There, Henry and the assembly renounced their allegiance to Pope Gregory VII and called for his abdication.

In response, Gregory excommunicated Henry, nullifying the oaths of loyalty and fealty taken by Henry’s subjects and vassals. Christians across Europe were prohibited from obeying the German king, and many of his supporters retracted their allegiances to him upon reception of the proclamation. Henry’s political crisis intensified when a group of influential lords of imperial territory issued him an ultimatum demanding that Henry submit to the pope or abdicate his throne. Over the following months, Henry faced significant opposition from within his kingdom. He maneuvered his politics and public appearances to portray himself as the preeminent force in Europe, while Gregory supported the ultimatum and the threatened election, rather than hereditary succession, of a new king.

In January 1077, Henry traveled to northern Italy and met Gregory at the castle of Canossa, the ancestral home of the influential Matilda of Tuscany (1046-1115), to plead for the absolution of his excommunication. Henry’s arrival at castle walls and the subsequent events atop the wintry Apennine ridge became immortalized as the Walk to Canossa. The German king indeed received his absolution in exchange for his public repentance outside the castle and his submission to the pope, but these actions shifted the equilibrium of medieval politics. By submitting to Gregory, Henry acknowledged the right of the pope to depose secular monarchs and inadvertently substantiated Gregory’s claim of church superiority over secular powers.

Civil War

Despite Henry’s submission, the anti-imperialist opposition denounced the German king and elected Rudolf of Rheinfelden, the Duke of Swabia, as Henry’s replacement, initiating a civil war known as the Great Saxon Revolt (1077-1088). Henry gradually regained support among German nobles and bishops despite contradicting his submission to Gregory and was once again excommunicated in 1080. Soon after, Rudolf of Rheinfelden died, and Henry’s army began a lengthy siege of Rome. As Rome slowly fell to the Germans, Henry deposed Gregory VII as pope by installing Wibert of Ravenna as Pope Clement III (r. 1080-1100) and was subsequently confirmed as Holy Roman Emperor by his new pope. The siege of Rome succeeded in 1083 and Gregory VII was held captive for the following year until Robert Guiscard (c. 1015-1085), the Norman duke of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily, forced Henry’s army north, sacked the city in 1084, liberating the pope. Gregory remained deposed and fled into exile in southern Italy, where he died in 1085.

Henry continued to practice lay investiture and simony throughout his kingdom as his control of imperial territory recovered, though the insurgent rulers of Bavaria, Saxony, and Tuscany, among others, maintained their opposition. Henry invaded northern Italy once again in 1090 to quell an uprising by an anti-imperialist coalition led by Matilda of Tuscany, Welf IV of Bavaria (c. 1035/1040-1101), and the Gregorian successor Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099). Their armies repelled the invasion and, in 1093, assisted the rebellion of Henry’s eldest son Conrad. The marriage of Matilda and Welf V, heir to Bavaria, was dissolved in 1095, giving Henry the opportunity to reconcile his differences with Welf IV. Conrad’s revolt collapsed by 1096, and Henry regained his influence in the following years, but he ultimately abdicated his imperial throne in 1105 following the betrayal of his younger son and chosen heir, Henry V.

Resolution & Legacy

Upon ascension to the imperial throne following his father’s abdication, Henry V received the support of the German upper nobility and reform-minded rulers within the empire, but the papal-imperial relationship went virtually unchanged. Pope Paschal II (r. 1099-1118), like his reformist predecessors, pursued the independence of the church from secular interference and rejected Henry’s investiture rights. In 1111, following a failed compromise over lay investiture, Henry had Paschal abducted, demanding the pope to acknowledge his investiture rights and to crown him Holy Roman Emperor. Paschal’s submission to Henry was nullified after his release by a church council on the basis of his imprisonment. Henry’s actions turned the previously supportive German bishops and clergy against him and gave secular rulers, mostly in Saxony, a reason to object to Henry’s imperial control of their lands. The disagreement over investiture and the tension between the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy continued even as the pope settled similar conflicts with the French and English monarchies.

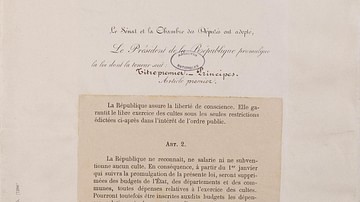

Resolutions to the investiture conflict proposed throughout the decades of conflict hinged on the division between the spiritual and secular roles of bishops. Negotiations between the two factions gained ground in 1121, and the compromise eventually known as the Concordat of Worms was finalized in 1122. The agreement between Henry V, his noble vassals, and Pope Callixtus II eliminated lay investiture by asserting that bishops "were to be chosen according to canon law and free from simony" (Wilson, 60) and could only be installed by "the relevant archbishop accompanied by two other bishops" (Whaley, 43). The emperor maintained the authority to invest bishops with secular authority and property, making them vassals of the lay rulers, but the feudal installment carried no religious significance and left the selection of bishops to the church authorities. The emperor’s investment of bishops was purely within secular jurisdictions, while spiritual authority came only from the proper church officials.

The terms of investment and governance agreed upon in the Concordat of Worms transformed the relationship between church and state. Contemporary historians generally agree that the Investiture Controversy shifted the structure of European politics. Wilson noted that the resolution "has widely been interpreted as marking an epochal shift from the early to high Middle Ages, and the start of secularization" (60). Cantor considered the Investiture Controversy to be "the turning point in medieval civilization," and explained further:

[The conflict] was the fulfillment of the early Middle Ages, because in it the acceptance of the Christian religion by the Germanic peoples reached a final and decisive stage. On the other hand, the pattern of the religious and political system of the High Middle Ages emerged out of the events and ideas of the investiture controversy. (246)

Although the responsibilities and capabilities of all parties were altered, the conflict over secular and religious authority had existed for centuries before the dispute over investiture, and it continued to influence European society for centuries to come.