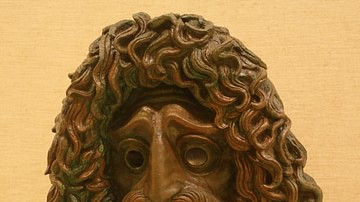

Iphigenia in Aulis (or at Aulis) was written by Euripides, the youngest and most popular of the trilogy of great Greek tragedians. The play was based on the well-known myth surrounding the sacrifice of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra's daughter Iphigenia. With the winds silenced by the goddess Artemis, the young girl's sacrifice at the goddess's altar would allow the Greeks to sail to Troy, win the Trojan War, and retrieve Menelaus's wife Helen. The tragedy was written sometime between 408 and 406 BCE and produced after the poet's death by his son in 405 BCE. As part of a trilogy, it won first place at the competition at the Dionysia in Athens - only the playwright's fifth first-place finish

Life of Euripides

Very little is known of Euripides' early life. Born in the 480's BCE on the island of Salamis near Athens to a family of hereditary priests, he preferred a life of solitude, alone with his books. There are even rumors - mostly dismissed - that he lived isolated in a cave. He was married and had three sons, one of whom, also named Euripides, became a noted playwright. Unlike his contemporary the elder Sophocles, Euripides played little or no part in Athenian political affairs; the one exception was a brief diplomatic mission to Syracuse in Sicily. Of his over 90 plays, 19 have survived which is more than any of his contemporaries. The poet made his debut at the Dionysia competition in 455 BCE, not winning his first victory until 441 BCE. Unfortunately, his participation in these competitions did not prove to be very successful with only four victories during his lifetime.

With the Peloponnesian War waging, Euripides left Athens in 408 BCE at the invitation of King Archelaus to live the remainder of his life in Macedonia. Although he may have written some of his best plays there, he left Athens embittered after seeing lesser-known playwrights win at the competition. Although often misunderstood during his lifetime and never receiving the acclaim he deserved, he became one of the most admired poets decades later, influencing not only Greek but Roman playwrights.

Years after the playwright's death, the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) called him the most tragic of the Greek poets. Sophocles admired his fellow tragedian by saying that Euripides saw men as they are not as they ought to be. Classicist Edith Hamilton, in her book The Greek Way, agreed when she wrote that he was the saddest of all of the greats, a poet of the world's grief. “He feels, as no other writer has felt, the pitifulness of human life, as of children suffering helplessly what they do not know and can never understand.” (205) She added no poet's work was “so sensitively attune as his to the still, sad music of humanity, a strain little heeded by that world of long ago” (205). In his book Greek Drama, Moses Hadas said that audiences would come to appreciate his style and outlook viewing his plays as more sympathetic than those of his contemporaries. It has been said that when Athenians speak of “the poet” they are referring to Euripides.

A Brief Summary of the Play

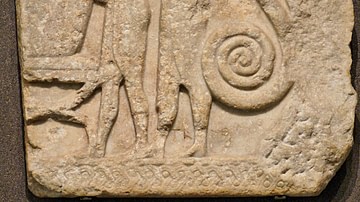

The play begins with ships and soldiers from all over Greece gathered at the port of Aulis in Boeotia. Unfortunately, they cannot or are unable to sail because the goddess Artemis has quieted the winds, for some unspecified reason Agamemnon has angered her. The Argive king has been told by a seer that in order to sail to Troy he must sacrifice his eldest daughter Iphigenia. As the Greek armies grow restless, Agamemnon writes to his wife to bring their daughter to Aulis to marry the warrior Achilles. However, after rethinking the plan, he sends a second letter telling Clytemnestra not to come. His brother Menelaus intercedes and the letter is never received. As the two brother's debate the issue, Agamemnon's wife, daughter and infant son Orestes arrive. Iphigenia is elated at the idea of marrying Achilles. Unfortunately, the idea of marriage is news to the Greek hero. When the truth is finally revealed to Clytemnestra, Achilles and Iphigenia, they confront Agamemnon. Outside the commander's tent, the troops become more and more restive - there is the possibility of a mutiny even among Achilles own troops. Achilles stands prepared to defend his almost-bride. Realizing the seriousness of the matter, Iphigenia decides that the correct thing to do is to submit to the sacrifice. In the end - in a strange twist and possibly not part of the original play - the grief-torn Clytemnestra learns that before her daughter can be sacrificed Iphigenia disappears and is replaced by a deer.

Cast of Characters

- Agamemnon, Argive king and commander

- Menelaus, Agamemnon's brother

- Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon and Iphigenia's mother

- Iphigenia

- Achilles

- Orestes

- Chorus of women from Chalcis.

- and a Greek warrior, a servant, an infant and a messenger

The Play

Agamemnon stands nervously before his tent at the Greek camp in Aulis. He recounts a story to his elderly servant of how he met and married his wife Clytemnestra. He recalls how his brother Menelaus met and married Helen - the same Helen who ran away with Paris to Troy. Menelaus “furious with desire” now sought retribution. “So all the Greeks sprang to their arms, and now they've all come here to the narrow straits of Aulis with many ships and shields and horses and chariots. (96) Unfortunately, the winds have been calmed by Artemis, preventing the ships from sailing. Calchas, the seer, has prophesized that Iphigenia, his daughter, must be “slaughtered for Artemis, the goddess of this place. If she were sacrificed then we would sail and overthrow the Phrygians.” (97)

In order to sacrifice his daughter, Agamemnon must first lure her to Aulis. He sent a letter to Clytemnestra asking her to bring Iphigenia to the camp with the promise that she is to marry the Greek warrior and hero Achilles - something of which Achilles is completely unaware. However, now he has had a change of heart and plans to send a second letter to stop her from coming. Speaking to his servant, “I did this wrong! Now I'm setting things right by writing this letter which you saw me sealing in the dark.” (97) The old servant leaves to take the letter to the Argive queen but soon returns with Menelaus at his side. Menelaus tells the servant ”to keep your place or you'll pay for it in pain.” (104) He takes the letter from the servant's hand despite the old man's protests. “You had no right to open the letter I carried.” (104)

As Agamemnon appears, the old man hastily departs. Menelaus hands his brother the letter, threatening to share the contents with everyone. ”I was watching to see if your daughter had arrived at camp out of Argos.” (106) He asks his brother, “Have you forgotten when you were eager and anxious to lead the Greek army to Troy, wanting to appear unambitious but in your heart eager for command?” (107) He further reminds Agamemnon of the prophecies of the seer and how he had promised to slay his child. However, now the king has changed his mind allowing the “worthless barbarians” to slip away. The irritated Agamemnon defends himself by saying that Menelaus had “governed” his wife poorly. “Should I pay the price for your mistakes, when I am innocent?” (109) He adds, “…are you crazed, for the gods, being generous, rid you of a wicked wife, yet now you want her back.” (109)

Agamemnon attempts to explain his sudden change in heart. “If I were to commit this act against the law, right, and the child I fathered each day, each night, while I yet lived would wear me out in grief and tears.” (109) As a messenger enters, Menelaus calls his brother a traitor. The messenger informs Agamemnon and Menelaus that Clytemnestra, Iphigenia and the infant Orestes have arrived in camp. The Argive king responds, “What words can I utter or with what courteous receive and welcome her?” (112) Her appearance can only mean disaster. Agamemnon is close to tears. “I am ashamed of these tears. And yet at this extremity of misfortune I am ashamed not to shed them. (112) Seeing this, Menelaus tells him, “I retract my words. I stand new in your place and beseech you do not slay your child and do not prefer my interests to your own.” (113) But in a bizarre twist of events Agamemnon thanks his brother but now believes he must slay his daughter. He speaks of the army that stands outside, waiting anxiously to sail to Troy. He fears that the army will hear of the prophecy and how he suddenly annuls his promise. In retaliation, they could easily kill both he and Menelaus and then slay the young girl. “…I am quite helpless, and it is the gods' will” (116)

Clytemnestra, Iphigenia, and Orestes appear before the tent. Agamemnon emerges from inside to the delight of his young daughter. Still under the delusion that she is to marry Achilles, she says, “…it is a good and wonderful thing you have done - bringing me here.” (120) Agamemnon tells her of a “long parting about to come for both of us.” (121) He adds, “I must dispatch the armies, but there is something still hindering me.” (122) He tells her that she is to take a long “sailing.” She is to go alone, without her mother and father. After she wishes him a quick return from Troy, he tells her he must first make a sacrifice. As she leaves the tent he begins to cry.

Still maintaining the pretense of an arranged marriage of Iphigenia to Achilles, Agamemnon tells Clytemnestra of Achilles and his family - Peleus and Thetis. “So such a man is your daughter's husband.” (126) When the Argive queen asks of the sacrifice to Artemis, the king responds that he has made all the necessary preparations and that afterwards, the marriage will take place. Then, he tells her to return to Argos to care for their youngest daughters. She, of course refuses. “You go outside and do your part, I indoors will do what's proper for the maids marrying.” (128)

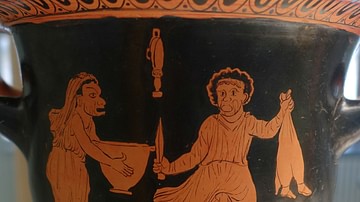

Achilles arrives at the tent looking for Agamemnon, telling of the anxious soldiers waiting outside: they have left their homes and families and sit “idly on the beaches” - all for a passion that has seized Greece. Clytemnestra exits the tent and speaks to Achilles, introducing herself. As he begins to leave she casually speaks of his betrothal to Iphigenia. Achilles is shocked - he has never courted her daughter. Immediately, she realizes that they have both been lied to. “My lady, perhaps it is only this: someone is laughing at us both.” (133) The old servant of the king enters and is cornered by the queen - he must tell both her and Achilles the truth. 'I'll tell you quickly. Her father plans with his own hands to kill your child.” (135) He speaks of the prophecy of Calchas and how after the sacrifice they will sail to Troy so Menelaus can bring Helen back. The marriage was a lie. She has been brought to Aulis for “death and destruction” as a sacrifice to Artemis. He adds that there was a second letter asking her to remain in Argos but it was intercepted by Menelaus. Achilles is livid. “I hear the story of your fate and misery and I cannot bear my part in it.” (137)

Clytemnestra asks him to protect both her and her daughter. “Although no marriage yokes you to the unhappy girl, but in name at least you were called her lord and her dear husband.” (138) Achilles promises to protect her and that Iphigenia will not be killed by her father. “… I cannot endure the insult and injury that the lord Agamemnon has heaped upon me.” (140) Achilles tells them they must speak to Agamemnon and persuade him, but Clytemnestra responds that her husband is a coward and afraid of the army. He advises her to speak to her husband alone. After Achilles leaves, the Argive queen meets her husband outside the tent. She calls for their daughter. Clytemnestra confronts Agamemnon with the truth. “Do you intend to kill her?” (147) He has been caught in a lie. She challenges him - he is killing their daughter just to get Menelaus his wife back. When he returns home from Troy, will he be able to embrace his children - would it be an outrage? Iphigenia asks why Paris must be her ruin. Agamemnon tries to defend himself - if he does not heed the prophecy then he cannot sail to Troy. The armies are primed to go. “Greece turns to you...and never by the barbarians in their violence must Greeks be robbed of their wives.” (153)

Achilles approaches the tent, telling them of the anxious army, an army led by Odysseus that cries for her to be slaughtered. He was even threatened with being stoned himself, being told he was a slave to marriage. However, he still promises to protect them. Iphigenia will not be killed. Iphigenia consoles Achilles, telling him that he is not to be blamed for the actions of the army. She then turns to her mother, “I shall die - I am resolved - and having fixed my mind I want to die well and gloriously putting away from me whatever is weak and ignoble.” (160) Her sacrifice will enable them to sail to Troy and be victorious. “...if Artemis wishes to take the life of my body, shall I, who am mortal, oppose the divine will? (161) Achilles speaks of her noble spirit but still wishes to stop her sacrifice. Clytemnestra begins to cry, but Iphigenia says that she does not want to be mourned; the altar of Artemis will be her monument. In parting, Iphigenia hugs her little brother. Lastly, she defends her father for he was acting against his will - for the sake of Greece. She exits. At the play's closing, the chorus speaks of her bravery as she is led to the altar.

There is a short appendix to the play - an alternate ending - which many believe is not genuine. In it Iphigenia has been taken away and a deer replaced her on the altar. A messenger tells the queen"

Clearly your child was swept to heaven; so give over grief and cease from anger against your husband. No mortal can foreknow the ways of heaven. Those whom the gods love they rescue. (174)

Assessment

Iphigenia in Aulis was part of a trilogy written by Euripides. Considered to be the saddest of the great Greek poets, Euripides left his home in Athens to live the remainder of his life in Macedonia. Although it would win first prize in 405 BCE at the Dionysia in Athens, victory, unfortunately, came after the playwright's death in 405 BCE. Unappreciated during his lifetime, he would influence countless others long after he died. Some believe the play was left unfinished or rewritten only to be completed by someone else, possibly Euripides' son. Oddly, the original ending of the play has Iphigenia being led to her sacrifice at the altar of Artemis; however, a new conclusion has Iphigenia rescued and replaced at the altar by a deer. Whether the play as it now appears was the same one penned by Euripides, it was one of the poet's most popular. It is sad that he could not have lived long enough to enjoy the accolades.