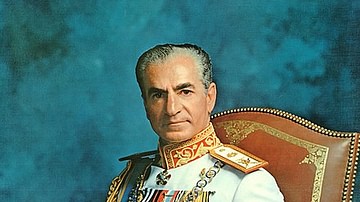

The Iranian Revolution (1978-1979) was the social movement that arose from widespread and diverse discontent with the monarchic government of Iran. The revolution was fought against the regime of Mohammad Reza Shah (r. 1941-1979), and it culminated in the end of the Pahlavi dynasty and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1979 to present).

The Iranian Revolution originated from deep-rooted problems that preceded the Pahlavi dynasty (1925-1979). There was deep dissatisfaction with the lack of democracy in Iran, the economic conditions, the religious immorality of the monarchy and wider society, and the enduring presence of foreign forces. The constitutional revolution (1905-1907) took place to express these dissatisfactions and to protest against the rule of the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925). It resulted in the establishment of a constitution and the Majlis, an elected representative parliament. However, the maintained proximity of the shah to foreign forces remained unpopular and eventually led to the demise of the Qajars, and the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty.

The new shah, Reza Shah Pahlavi (r. 1925-1941), instigated a programme of 'modernisation', which would be continually pursued in the reign of his successor, Mohammad Reza Shah, despite significant disapproval from religious leaders. The Pahlavi dynasty, although popular at times, became a symbol of Western immorality and religious sacrilege. Protests became a regular feature of Iranian society, and the revolution of 1978-9 ultimately established the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Constitutional Revolution

In late 19th- and early 20th-century Iran, there was increasing unrest among secular intellectuals and the Shia clergy against the rule of the Qajar dynasty, which they argued did not resist enough foreign economic and political interference.

This discontent led to the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1907. Groups opposing the rule of Mozaffar o-Din Shah (r. 1896-1907) led long economic strikes and protests in most major cities across Iran. In October 1906, a constitution was drawn up that included limitations on royal power and the introduction of an elected representative parliament (called Majlis). The Shah died five days after signing the constitution, on 3 January 1907. Along with the Supplementary Fundamental Laws passed in early 1907, which provided freedom of speech, press, and association, the constitution marked a new democratisation in Iran and the precedent for a popular uprising that led to successful political upheaval.

The Qajar dynasty was eventually overthrown in the Persian coup d'etat of February 1921 after military officer Reza Khan led the Persian Cossack brigade to seize power. Reza Khan was placed on the throne, becoming Reza Shah Pahlavi, the first monarch of the new Pahlavi dynasty.

Reza Shah Pahlavi

Reza Shah Pahlavi's main objectives were to strengthen the central government and to 'modernise' Iran by aligning it more closely to Europe politically, socially, and economically. Part of his 'modernisation' programme was to limit the power of the religious hierarchy, which he carried out in many different areas. Reza Shah created a system of secular education, including the establishment of the European-style university in Tehran in 1935, and allowed women to participate. In a more active effort to limit the power of the religious hierarchy, Reza Shah established a codification of laws to create a body of secular law, prohibited clerics from being judges, and moved the role of notarising documents from clerics to state-licensed notaries. Furthermore, in 1932, a European dress code was enforced, and, in 1936, wearing the veil was explicitly prohibited.

While Reza Shah had been very popular, his intolerance of political dissent alienated intellectuals, who wanted a more democratic government, and the Shia clerics. His police and the army became increasingly violent. The Goharshad Mosque Rebellion on 13 July 1935 exemplified the shift in the army, when troops violated the sanctity of the shrine of Imam Reza in Mashhad, killing dozens of worshippers who gathered there to protest the Shah.

Reza Shah eventually abdicated on 16 September 1941, after the invasion of Iran by Britain and the USSR. His son succeeded him on the throne, becoming Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Oil & Mossadeq

The occupation of Iran brought the country even closer politically to Western powers, which led to further popular discontent with the Pahlavi government. The incorporation of Iran into the Second World War (1939-45) meant food became scarce, inflation severely increased, and the presence of foreign troops fed into xenophobia and nationalist discourses. Furthermore, the Majlis, who had propertied interests, were not effective in quelling these issues, leading to a rise in support for the communist Tudeh Party, which was actively organising industrial workers.

Iran's most profitable export, oil, was the arena for foreign involvement in government. From 1944 onwards, the Soviet and American governments competed in negotiations for oil concessions from Iran, which led to Soviet propaganda attacks and military invasions. Soviet troops eventually withdrew in May 1946, after the government signed an oil agreement with the USSR.

1948 saw an increase in popular desire for oil nationalisation in Iran, as it had been made clear that the British government earned more revenue from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company than the Iranian government derived from royalties. On 15 March 1951, the Majlis, now led by the leader of the National Front (and later named Prime Minister in April 1951) Mohammad Mossadeq, voted to nationalise the oil industry.

Mossadeq's popularity, anti-West politics, and intransigence regarding the nationalisation of oil created friction between him and the Shah. In June 1953, the US and the UK joined forces to overthrow Mossadeq in Operation Ajax. The Shah, cooperating with the US CIA, dismissed Mossadeq and four days of rioting ensued, during which Mohammad Reza Shah left the country. On 19 August 1953, pro-Shah army units, financed by the USA and UK, defeated Mossadeq's forces, the Shah returned to Iran, and Mossadeq was imprisoned.

A period of political repression followed as Mohammad Reza Shah tried to concentrate power in his own hands. Nationalist and communist parties were repressed, the media was restricted, the secret police (SAVAK) became stronger, and elections were carefully controlled.

Clerical Discontent

Shia clerics were growing increasingly unsatisfied with the Pahlavi dynasty's commitment to Islam (or lack thereof). The modernisation project that had been pursued since Reza Shah's reign was consistently subject to criticisms by the religious hierarchy, especially the enforcement of European dress codes and the prohibition of the veil, which was interpreted as a symbol of the erosion of traditional Islamic values. In 1944, a mid-ranking cleric, Ruhollah Khomeini published a book, Kashf al-Asrar (Secrets Unveiled), that attacked the Shah's modernisation project and its anti-clerical policies.

Religious-secular debates had been a regular feature of the political landscape in Iran since the Constitutional Revolution. They rose to prominence again after the announcement of Mohammad Reza Shah's 'White Revolution' in January 1963, a 6-point modernisation programme that included land reform, nationalisation of forests and pastureland, and the sale of government factories to private interests. The programme also proposed the enfranchisement of women and allowing non-Muslims to hold office, which most Shia clerics deemed unacceptable. In June 1963, now-Ayatollah Khomeini was arrested in Qom for a speech attacking the Mohammad Reza Shah and the 'White Revolution'. His arrest led to three days of country-wide protests, the most violent since the overthrow of Mossadeq ten years prior, which were eventually severely suppressed by the Shah.

In October 1964, the government proposed a bill that would grant diplomatic immunity to US military personnel serving in Iran and their families, essentially allowing Americans to bypass Iranian courts. The bill was deeply unpopular, especially among clerics who viewed the US as the epitome of Western immorality. Khomeini, having been released from house arrest in April 1964, attacked the bill in front of a large audience in Qom. Recordings of this sermon were circulated widely and drew considerable attention to the religious anti-Shah movement. Within days of this sermon, Khomeini was arrested again and exiled to Turkey, from where he moved to Iraq in October 1965.

Khomeini continued to release anti-Shah statements from exile. In the late 1960s, Khomeini delivered a series of lectures to students which were then published and disseminated as a book titled Velayat-e Faqih (Rule of the Islamic Jurist). He argued that monarchy as a form of government was wholly incompatible with Islam.

Meanwhile, younger Iranians formed several underground guerilla groups against the regime as legal opposition seemed ineffective. Most groups were forcefully disbanded by the regime, but two main groups survived: the Fedayan (Fedayan-e Khalq), who were ideologically Marxist and anti-imperialist, and the Mojahedin (Mojahedin-e Khalq), who saw Islam as the foundation of their political struggle. Both groups used similar tactics to undermine the Shah's regime: they attacked police stations, bombed US, British, and Israeli offices, and assassinated Iranian security officers and US military personnel.

Political Turmoil & Unrest

By 1976, the Iranian economy was struggling. The Shah had tried to use the increased oil revenue after the OPEC crisis to expand Iranian industry and infrastructure beyond its human and institutional resources. This caused widespread economic and social dislocation. As part of the wider modernisation programme, the government used the increased funds to nationalise private secondary schools and community colleges, reduce income taxes, and implement an ambitious health insurance plan. However, these programmes did not effectively combat inflation or soaring house prices.

By 1978, there were over 60,000 foreigners, including 45,000 Americans, in Iran, which strengthened the popular perception that the Shah's modernisation programme was eroding the country's Iranian character and Islamic values and identity. Political repression increased as a response to increasing popular dissent and the establishment of a one-party state, which further alienated educated classes. From 1977 onwards, human rights organisations started to draw attention to human rights abuses in Iran, which US President Carter made part of his foreign policy to combat. The Shah responded by releasing political prisoners and announcing new legal protections for citizens. Taking advantage of this new political freedom, the National Front, the Iran Freedom Movement, and other political groups started acting and organising again.

While the protests of 1977 were primarily middle-class and secular, the protests in the first half of 1978 were led by religious figures and drew support from more traditional groups and the urban working classes. The protesters increasingly engaged in calculated violence; the most objectionable features of the regimes were targeted. For instance, nightclubs and cinemas were symbols of moral corruption and Western influence, banks were symbolic of economic exploitation, and police stations were representations of the violence of the Pahlavi regime.

Anti-shah slogans and posters also shifted to using Khomeini as the face of a revolution and the proposed leader of an ideal Islamic state. From exile, Khomeini continued to urge further demonstrations and warned against any compromise with the regime. In August 1978, over 400 people died in a fire started by religiously-inclined students at the Rex Cinema. Government popularity declined further as a result of a successful rumour that the fire was the work of the secret police, and not by religiously-inclined students.

The Revolution

On 4 September 1978, the end of Ramadan, anti-government demonstrations began to spread across Iran and had an increasingly radical tone. The government declared martial law in Tehran and 11 other cities. The Jaleh Square Massacre took place on 8 September, when Mohammad Reza Shah's troops fired into a crowd of 20,000 pro-Khomeini protestors in Tehran. The official death toll, as given by the government, ranges between 84 and 122, though the actual figure is widely disputed, with the number likely being higher. The day became known in Iran as 'Black Friday', and led to greater discontent with the government.

Khomeini, having been expelled from Iraq in 1978, had moved to France, which gave his opposition movement wider exposure in the global media, and the better telephone connection allowed for improved coordination among the opposition movements.

In September 1978, workers in the public sector and the oil industry began regularly striking on a large scale, demanding better pay and working conditions. These demands transformed into calls for political change, as the movement joined momentum with wider anti-Shah demonstrations. The scarcity of fuel, transport, and raw materials led to private industries halting practically all proceedings by November. The Shah, recognising his grasp on Iranian society slipping, closed the schools and universities, suspended newspapers, and prohibited meetings of 4 or more people in Tehran. He attempted to bring peace by ordering the release of over 1000 political prisoners, including Ayatollah Hosain Ali Montazeri, an associate of Khomeini. However, these capitulations did not have the desired effect. Khomeini called the promises worthless and called for the continuation of protest. The strikes resumed, leading to a total government shutdown.

On 10 and 11 December, hundreds of thousands of people participated in anti-regime marches across the country, leading to violent clashes between protesters and the Shah's troops. The Shah subsequently entered discussions with National Front leader, Shapour Bakhtiar, who agreed to form a government under the Pahlavi dynasty provided the Mohammad Reza Shah left the country. On 3 January 1979, the Majlis voted in favour of Bakhtiar forming a government, and on 6 January, Bahktiar presented the Shah with his new cabinet. On 16 January, Mohammad Reza Shah fled Iran, with celebrations breaking out across the country as the news spread.

Bakhtiar Government

Prime Minister Bakhtiar immediately attempted to distance his cabinet from the Shah's regime by lifting press restrictions, freeing all remaining political prisoners, and promising the dissolution of SAVAK. While this compromise of a government won the support of moderate clerics, most demonstrators, led by Khomeini and leftist ideologies, remained committed to ending the monarchy. The National Front expelled Bakhtiar from the party for capitulating to the Pahlavi regime, and Khomeini declared his government illegal. On 29 January, Khomeini called for a 'street referendum' on the monarchy leading to a massive demonstration of over one million people in Tehran.

On 1 February, Khomeini finally returned to Iran, where he was greeted with a rapturous welcome. In a speech the next day, he named Mehdi Bazargan as the prime minister of the provisional government. In the following days, the loyalty of the armed forces to Bakhtiar waned, and on 8 and 9 February, the air force declared a new loyalty to Khomeini. The air base arsenal was subsequently opened and weapons were distributed to crowds. On 11 February, senior military commanders announced the 'neutrality' of armed forces, which was essentially tantamount to withdrawal of support for the government, and by late afternoon, Bakhtiar was in hiding and the capital was in rebel hands: the Pahlavi dynasty had collapsed.

The Aftermath - Bazargan & Provisional Government

By Khomeini's proclamation, Bazargan became the first prime minister of the revolutionary regime in February 1979. However, the country was still ablaze with revolutionary sentiment, meaning the government had little control over society or its own bureaucracy. Since the establishment of hundreds of semi-independent revolutionary committees during the revolution, there was no longer an effective central authority.

Khomeini did not consider himself to be bound by the government; he made his own policy pronouncements, named government representatives, and established new institutions without Bazargan. The prime minister was now to share power with the Revolutionary Council, an institution established by Khomeini in January 1979. New revolutionary courts were established to try and punish collaborators with the former regimes. From that point onwards, executions of military and police officers, SAVAK agents, cabinet ministers, and Majlis deputies took place daily. The harsh activities of the courts were very controversial, and, on 14 March, Bazargan insisted revolutionary courts suspend activities. However, on 5 April, the courts were reauthorised by the Revolutionary Council. Over 550 people had been executed before November 1979, when Bazargan finally resigned.

Khomeini, in his attempts to Islamise Iran, established various institutions to do so, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a military force loyal to the clerical leaders that grew in force rapidly. Bazargan had become essentially powerless. A national referendum was held on 30 and 31 March 1979 to determine the country's political system post-monarchy. However, voting was not secret, and there was only one form of political system on the ballot: Islamic Republic. On 1 April, Khomeini declared the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The constitution was subsequently rewritten to establish a basis for clerical domination and to give ultimate authority to Khomeini as the faqih (known as Leader of the Revolution and as the heir to the mantle of the Prophet).

Khomeini, populist preachers, and left-wing parties stoked the flames of already widespread anti-American sentiment. In October 1979, the former shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was admitted for medical treatment in the USA, which concerned the Islamic Republic, as they feared his illness would be used to secure US backing for a coup against the revolution. After Bazargan met with US President Carter's national security advisor in Algeria, hundreds of thousands of people protested in Tehran, with some students 'of the Imam's line' occupying the US embassy, holding 52 US diplomats hostage. 2 days after the protests broke out, Bazargan resigned from his role on 6 November 1979. The Revolutionary Council took over the prime minister's functions, pending presidential and Majlis elections. The Iran hostage crisis lasted for 444 days and resulted in the complete breakdown of US-Iran relations.