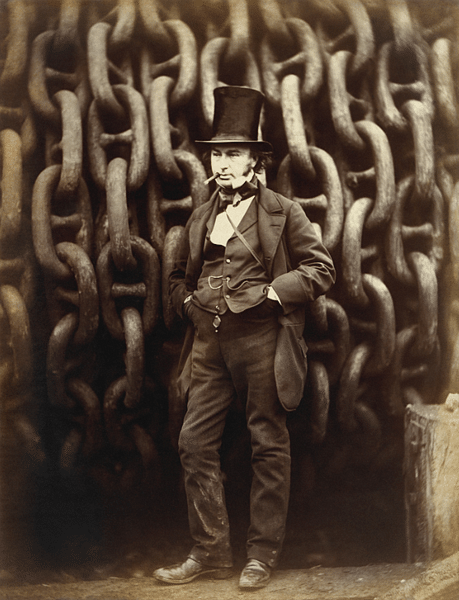

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) was a British engineer and a key figure of the British Industrial Revolution (1760-1840). Brunel masterminded the Great Western Railway from London to Bristol, designed and built innovative giant steamships like SS Great Britain, constructed bridges and tunnels, and aided casualties in the Crimean War by designing the innovative Renkioi Hospital.

Time and again, Brunel pushed the boundaries of what was considered possible in engineering. His projects usually struggled to gain sufficient funding, and they almost always ran over budget. The realisation of such ambitious schemes as the Clifton Suspension Bridge, the straight and fast Great Western Railway, and the biggest steamship yet built, meant that the history books have been much kinder to Brunel's achievements than his investors ever were.

Early Life & Character

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in Portsmouth, England, on 9 April 1806, the only son of Marc Isambard Brunel (1769-1849), a French-born engineer of note now living in England. Isambard's mother was Sophia Kingdom, daughter of a Plymouth naval contractor. Isambard was sent to a boarding school in Hove and then, to remember his family's roots perhaps, to study in Caen and then Paris at the Collège Henri-Quatre from 1820. He gained several prizes but left the college still in his teens to become an apprentice under the famous watchmaker Louis Breguet. Isambard returned to England in 1822. He next worked as an intern in the famed workshop of Henry Maudslay in Lambeth, London. Proving himself an able draughtsman, mathematician, and keen observer of architecture, he inserted himself immediately into his father's engineering projects, notably the Thames Tunnel.

The biographer S. Brindle gives the following summary of his forceful character and tastes:

He liked style in all things – certainly in his clothes; he loved the arts, picturesque landscape and eclectically ornamental architecture. He was class conscious, decidedly authoritarian with those he considered his social inferiors…Brunel, although a most modern man in his professional life, lived by an old-fashioned, somewhat snobbish but high-principled code of honour. Unlike the modern businessman, profit and commercial success were not all for Brunel.

(2-3)

Above all, "even by the energetic standards of the age, Brunel had an outstanding capacity for work" (ibid, 144). He slept only a few hours each night and kept himself going on his one, ever-present indulgence: giant cigars.

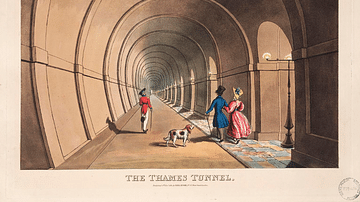

The Thames Tunnel

By 1820, congested London was in desperate need of an extra crossing of the River Thames, and so a tunnel was proposed. Marc Brunel had patented a tunnelling shield which would allow workers to excavate the soft ground under the river. Work began in 1824, but it turned out to be an almost never-ending task beset with problems. The tunnel seriously flooded twice. The first flooding came in May 1827 when the excavators reached a particularly thin patch under the river. The proximity of the mass of water above was confirmed when Isambard descended in a diving bell into the murky depths of the Thames. The gap was plugged by sinking around 150 tons of clay sacks into the hole, and the tunnelling continued.

Isambard, by now the resident engineer of the project and often accident-prone, suffered serious injuries when he fell into an uncovered water tank in October 1827. The second major flood in the tunnel occurred in January 1828. Six workers lost their lives. Isambard was caught in the massive wall of water that crashed into the tunnel and was only just saved from drowning by one of the workmen. The work carried on, but the tunnel project needed a cash injection from the government as the costs rocketed. The press labelled the never-ending tunnel project the 'Great Bore'. This project was a harsh lesson for Isambard that such grand projects needed not only engineering know-how, money, and luck but also a forceful personality driving the team forward to remove each and every obstacle that came along. The tunnel was officially opened on 25 March 1843 and is still used today.

Clifton Suspension Bridge

In 1829, Brunel, while still recuperating from his accident in the Thames Tunnel, submitted no fewer than four designs for the proposed bridge to span the dramatic gorge at Clifton, Bristol. One design was accepted, and work began on the now-famous Clifton Suspension Bridge in 1831. After countless delays, political interference, and a chronic lack of funding, Brunel would never see it finally opened for the public on 8 December 1864. It was the longest single-span suspension bridge yet built, soaring across 214 metres (700 ft) of fresh air to cross the Avon Gorge.

Brunel was often criticised for his arrogance; he was both infuriatingly mercurial (changing designs as he went along) and often dismissive of opinions that did not match his own. As the biographer, T. Bryan notes, though: "Brunel was deeply insecure, and his diaries reveal that he worried long and hard that all his 'castles in the air' would come crashing down" (153).

Great Western Railway

Next, Brunel was appointed the chief engineer of the Great Western Railway (GWR) in March 1833. Brunel had won the position through persuasion and his personality, tools he would use to good effect many times. He oversaw the building of the 190-km (118-mi) long railway line for GWR from Bristol to London which opened in 1838. This massive project involved designing several bridges (e.g. Chepstow) and tunnels, including the longest yet built, the 2,950-metre (9,678-ft) long Box Tunnel. More of these were required than usual because Brunel insisted on having the line run as straight and as flat as possible so that the trains could run faster. He designed the stations of Temple Meads (Bristol, opened in 1840) and Paddington (London, opened in 1854), as well as the station at Bath. The London-Bristol line opened in 1841 and was later extended into Devon and Cornwall, a stretch that included Brunel's Royal Albert Bridge over the Tamar River.

GWR ultimately enjoyed a reputation with the public for speed, comfort, and elegant design. Brunel was at the heart of these ideals, personally intervening in every single aspect of the railway from how many rivets to use in a bridge to the colours of the interior carriage decor.

On 5 July 1836, Brunel found time to marry Mary Horsley. The couple honeymooned in Wales and Isambard's favourite English region, the West Country. They had three children: Isambard (b. 1837), Henry Marc (b. 1842), and Florence. Isamabard Junior wrote a warm biography of his father in 1870. Family life in no way distracted him from his work, he even had meetings during his honeymoon. Brunel was so worried about wasting time he famously had no chairs in his office in London so that anyone who dared interrupt him could at least not sit and stay any longer than absolutely necessary.

One failure was Brunel's loss in what became known as the 'gauge wars'. At the time, different companies each ran lines in specific regions. Brunel had designed his trains to run on tracks with a broad gauge of 2.1 metres (7 ft) between the parallel rails. Other companies, notably those run by George Stephenson (1781-1848) and his son Robert Stephenson (1803-1859), inventor of the famed locomotive Rocket, used rails only 1.4 metres (4 ft 8.5 in) apart. The difference in gauges meant that many trains had to transfer their passengers or goods to a second train that was gauge-compatible with a new stretch of line. Brunel believed that his rails provided more stability and greater speed (since the trains could have a lower centre of gravity). It also meant that Brunel's wider trains could carry more goods. The drawback was that Brunel's tracks were more expensive to lay down (although not by much). In the end, the cost and the fact that there was already eight times more narrow gauge than broad gauge tracks in use were the decisive factors when the government passed the Regulating the Gauge of Railways Act in 1846. Thereafter, railway companies were obliged to adopt the smaller gauge tracks.

Brunel's Steamships

Not satisfied with limiting himself to railways, Brunel took a keen interest in ships, particularly, the possibilities of steam power. A steamship did not need to wait for the right winds, and it could steam in the straightest and shortest line between two ports. The problem with steamships, though, was that they had to carry their own fuel or make regular stops at coaling stations. At first, then, steam-powered ships were usually small vessels that plied rivers or made ferry crossings. Developments to the steam engine made it much more fuel-efficient, but nobody really believed that steamships could cross the world's oceans. Brunel was one of the few who thought they could, and his vision was to see that the solution to the fuel problem was to make steamships as big as possible. In this way, the space left for passengers and cargo could be sufficient to make the voyages profitable. Brunel formed the Great Western Steamship Company, and he designed and built a trio of giant ships: SS Great Western (1838), SS Great Britain (1843), and SS Great Eastern (1858).

Great Western

The wooden Great Western, with its steam-powered paddle wheels for propulsion, was something of a hybrid effort that blended new and old ideas. The ship came a narrow second in an effort to be the first steam-powered vessel to cross the Atlantic, but it was more efficient and faster than its rival (which had had a four-day head start). Great Western had also suffered a fire on its very first day; Brunel, while fighting the blaze, fell down a damaged ladder and was knocked unconscious. Great Western crossed the Atlantic 67 times and made a profit. Brunel was encouraged to try an even bigger and more radical design.

Great Britain

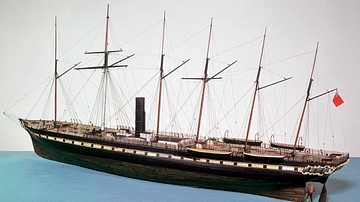

Great Britain was more innovative than its predecessor as it had a propellor for propulsion. A stern propellor was not a new idea but applying it to a giant steel ship was. Brunel designed a six-bladed propellor before changing it to a more efficient four-bladed one. Tests have shown that a modern propellor is only 5% more efficient than Brunel's design. Brunel demonstrated he was right that the weight and volume of a ship had no bearing on its efficiency in cutting through the water. The surface area of the hull, particularly that part which cuts through the water foremost, was the crucial consideration. Brunel knew that bigger is better for ships since the volume increases as a cube while the surface area only increases as a square. In practical terms, a giant metal ship would have plenty of space for coal and passengers. It was this idea that Brunel showed to the world, and so he revolutionised shipbuilding thereafter. Great Britain was so big it needed never-before-built giant steam engines designed by Brunel. The engines were supplemented by sails on the ship's six masts. Other innovations included a double-skin hull with overlapping plates for extra strength. The ship was a success on its early voyages from London to New York, but on its fifth crossing in September 1846, disaster struck. The ship ran aground on the coast of Ireland never having recovered its construction costs. Great Britain found a second life as a passenger liner to Australia, but Brunel had already moved on to his third great ship, the biggest of them all.

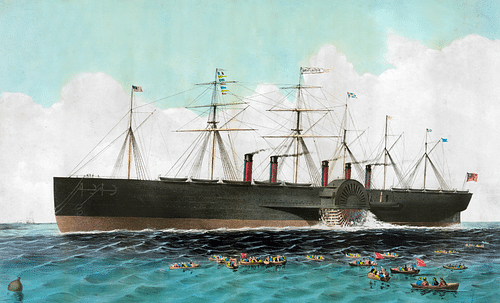

Great Eastern

Great Eastern took Brunel's idea of bigger is better even further. It was designed to sail the world's oceans without stopping anywhere for fuel. It was powered by paddle wheels, a propellor, and sails on its six masts. Brunel called the giant his 'great babe'. The enterprise was a great risk since no company had commissioned it, rather, Brunel hoped that when it became a reality, somebody would buy it. The project turned out to be the designer's most difficult yet. The giant ship needed its own special dock built. The constructor, John Scott Russell of Millwall went bankrupt in February 1856 with the ship only half finished. Brunel fought off creditors who wanted to sell the hull and give up. By force of personality, Brunel managed to persuade new investors and keep the project going. The ship was so big it had to be launched sideways using massive chains, but the launch in 1857 was a disaster; Brunel's carefully designed braking winches span out of control, and one man was killed. It took two more months to work out a way to safely lower the hull into the river. On 1 February 1858, Great Eastern was afloat and ready for fitting out. The original budget had rocketed from £14,000 to £120,000. Later in 1858, Brunel's construction company went bust. More investors had to be found. Bad luck seemed to follow Brunel, and Great Eastern was no exception. During the sea trials, a heater exploded, killing five men and blowing a funnel off the deck. Yet more money was sunk into the ship for the repairs. Finally, Great Eastern made its maiden voyage in June 1860.

With a length of 211 metres (692 ft) and displacement of 27,000 tons, Great Eastern easily became the largest ship ever built, a record it would hold for 49 years. It could carry 4,000 passengers and 418 crew across the Atlantic in just 10 days (compared to the average of 30 days under sail). Unfortunately, smaller ships could beat this, and speed became the primary concern of ocean travellers, meaning that Great Eastern made far less profit than everybody had hoped. Nevertheless, the great liners of the 20th century like RMS Lusitania (the new record holder for size) and RMS Titanic owed their existence to Brunel's vision half a century before.

Renkioi Hospital

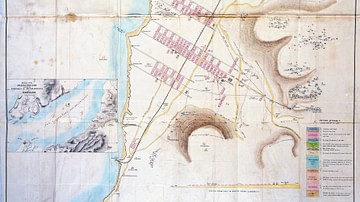

During the Crimean War (1853-56), the military disasters and the plight of the thousands of wounded stirred Brunel to turn his design skills to building an entirely new kind of hospital. The key requirements from the War Office were that it had to be available quickly and be easy to construct on-site. Brunel took only a few weeks to design a complex of prefabricated buildings. The idea for a prefabricated hospital likely came from the success of London's Crystal Palace, host of the Great Exhibition in 1851. Brunel had himself used prefabricated elements for Paddington Station. Another advantage of prefabrication was the hospital buildings could easily be extended if required.

The hospital provided 1,000 beds and incorporated the latest ideas on ventilation and sanitation as advocated by such nursing pioneers as Florence Nightingale (1820-1910). When disease was still the biggest killer in warfare, Brunel ensured it had excellent facilities for washing and good sanitation, including adapted bathrooms for invalids and fan ventilation. Each prefabricated part was designed so that it could be carried by one or two men only. Brunel also ensured only the most basic of tools were required to assemble the parts.

Ships, many of them, were needed to transport the 11,500 tons of material to its destination: Renkioi. Brunel meticulously planned the logistics required to get his hospital in place and then fitted out and supplied, everything from an iron laundry to toilet paper. The hospital was a success. Around 1,350 patients were treated there, and all but 50 made a recovery, an astonishing success rate for the period. Other nations were not slow to catch on to the idea. Brunel's hospital design was adopted, for example, by the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861-65).

Death & Legacy

Brunel endured failing health in his later years. Under tremendous stress with the Great Eastern fiasco, Brunel was diagnosed with a serious kidney complaint, Bright's disease. He spent the winter of 1858-9 in Egypt and Italy in the hope that a warmer climate might help his health improve. It did not. Brunel died of the effects of a stroke on 15 September 1859. He was buried in the family plot in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

Brunel was certainly one of the great engineers, perhaps the greatest of the British Industrial Revolution when one considers his achievements in railways, shipping, and civil engineering projects. The engineer was not without his critics, though. One recurring lament of investors and some journalists was that Brunel had great ideas but these were perhaps a little too grand for practical use. Not a lot of money was ever made from Brunel's great iron ships, certainly. This sentiment was expressed in an obituary in The Engineer magazine of September 1859: "However brilliant may have been Mr Brunel's career, it was, in many respects, an unfortunate one; and we believe, no-one felt this truth more keenly than himself" (Shelley, 108). A kinder assessment may be that Brunel was ahead of his time, so far ahead, that technology had yet to catch up with some of his designs. In the 20th century, the fields of engineering, architecture, and design became more specialised so that nowadays, Brunel would need at least eight different highly qualified professionals to match him. In short, "Brunel was the 19th century's answer to the Renaissance Man" (Brindle, 179).

Many of Brunel's works are still standing. Amongst others, the SS Great Britain can be visited today in Bristol, the Clifton Suspension Bridge still carries traffic, and parts of the Great Western Railway line are still being used, the latter being honoured by inclusion in UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites.