Ancient Israelite art traditions are evident especially on stamps seals, ivories from Samaria, and carvings, each with motifs connecting it to more general artistic traditions throughout the Levant. Ancient Israel, and therefore its art, existed from about the 10th century BCE until the late 8th century BCE and used both local and imported materials, as demonstrated by local limestone used for stamp seals and carved ivories that were possibly imported from Phoenicia. Common motifs in ancient Israelite art include plants flanked by animals, astral symbols (such as sun-disks and stars), adapted forms of Egyptian symbols (such as winged sphinxes, uraei, and falcons), various animals (such as lions, ostriches, and bulls), and monsters (such as Cherubs - creatures akin to the Lamassu).

As with most art in the ancient world, it is not clear who created the art, even in cases of stamp seals which may have been created by someone other than the one who is named on the seal. Likewise, due to the age and preservation of art from ancient Israel, it is not exactly clear how or where objects were manufactured; oftentimes, suggestions are educated guesses. In any case, whether we consider intricate ivories discovered in Samaria - the capital of Israel - or detailed stamp seals, Israelite materials and objects tell stories about society 2,700 years ago. Art reveals many aspects of the Kingdom of Israel: ongoing trade of luxury items among the upper class; perspectives on cult rituals, deities, and sacred objects; international networks; cultural concerns; and the role of cults and deities in ancient Israel.

Materials, Techniques, & Their Makers

Just modern artists choose different canvases and materials with which to work (e.g., clay figurine, wall, paper, etc.), so artists of ancient Israelite art used various materials. For example, limestone was used most often to create stamp seals, though other materials, such as semi-precious stones (carnelian, jasper, quartz, etc.), bone, clay, and ivory, were used, albeit less frequently. To create the stamp seal, lapidaries (artists who work with stone) would shape the canvas material into a smooth, scaraboid shape, measuring between 8 mm and 3 cm long. Though less common, conical, hemispheroid, and circular stamp seals were also used in ancient Israel. After creating a smooth, polished canvas, creators would inscribe designs into the seals through multiple methods: engraving images and words with a sharp, pointed tool; filing the edge of the stone; using a boring tool perpendicular to the seal; or wheel-cutting, “cutting with the head of a tool spinning parallel to the surface” (Seevers and Korhonen 2016). Ancient Israelite art is not particularly unique, though, and observations regarding materials and techniques also apply art in the broader Levant during the Iron Age.

Though ivories were discovered in Samaria, they were also common luxury items throughout Northern Syria. As such, ivories were carved and produced throughout the region, sometimes with multiple production centers throughout single cities. In order to create ivory carvings, a combination of tools was used: saws, broad- and pointed-edge chisels, flat chisels, bow drills, and other variations of these tools. Much remains to be learned, though, as our understandings come from informed inferences such as this description:

... the bulk of ivory around the sculptural forms of the cow and calf was likely removed using a combination of hand-powered drills, such as a bow-drill, and chisels. A similar combination may also have been used to create the deep recesses for the eyes of the cow and calf. (Lauffenburger, Anderson-Zhu, and Gates 2018)

Samarian Ivories: Luxury & Power

In the ancient Near East, ivory was a highly valued item. Ivory workshops existed throughout North Syria, which Samaria was a part of. Both biblical texts and archaeological evidence attest to the importance of ivory carving in the kingdom of Israel. For example, the Hebrew Bible refers to ivory houses that Yahweh will destroy (Amos 3:17). Supporting the Hebrew Bible's indication that carved ivories were important in the Kingdom of Israel, archaeologists recovered nearly 500 fragments of ivory art from Samaria in the 20th century CE. The ivory pieces show a wide variety of imagery and cultural influence, especially Egyptian, Phoenician, and North Syrian.

Consider, for example, ivory carved, crouching lions, uncovered at Samaria in the 1930s CE. Various scholars interpret these carvings as furniture inlays, meaning they were used to decorate the surface of furniture. Remarkably similar objects were uncovered at Sam'al (modern Zincirli) and Thasos (in the Aegean Sea). As early as the 1930s CE, scholars assumed the close relationship between art forms, like the crouching lions, meant that Israel imported ivory carvings from around the region, such as Damascus and Phoenicia. Though plausible, this is difficult to confirm.

Similarities between Samarian ivories and other sites in northern Syrian (e.g., Arslan Tash, Nimrud, Zincirli, etc.) can be a window into the social function of art. Textual evidence from the 9th century BCE indicates that the Kingdom of Israel and various other groups in the region formed a coalition to oppose Neo-Assyria. Presumably, forming a coalition would have involved visiting and hosting foreign leaders. In visiting foreign leaders, luxury items - like ivory carvings - would indicate to visitors Israel's wealth and, thereby, its power. Just as luxury items in the 21st century CE indicate social status, artwork in the Kingdom of Israel functioned as a signal to the viewer - whether foreign dignitary or commoner - that the King of Israel had power, wealth, and could afford luxury items, these were indicative of the kingdom's prestige in relation to places like Phoenicia, Nimrud, and Damascus.

Stamp Seals: Politics, Religion, & Networks

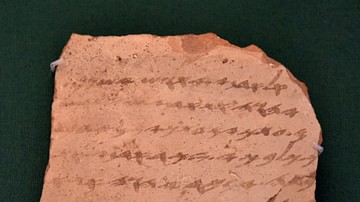

Stamp seals are objects typically inscribed with a name and artwork. To identify and authenticate other objects, people would press the stamp seal into wet clay. Likewise, stamp seals were used for clay envelopes, ensuring that messengers or other parties did not peak at the document. Notably, though, there is great diversity in stamp seals from the Kingdom of Israel, indicative cultural influences, political networks, and religious ideas.

Early on, Egyptian art heavily influenced the Levant. By the middle of the 2nd millennium, about 1500 BCE, nearly 40% of stamp seals represented scarab beetles. While some of these were produced in Egypt, it is likely that scarabs were also produced in Israel. For example, some stamp seals combine the Egyptian element, a scarab beetle, with non-Egyptian motifs, “such as the frontal depiction of a nude female, who may represent a goddess related to the fertility of plants and animals” (Eggler and Uehlinger, 16). Likewise, some stamp seals blend Egyptian and Canaanite deities, such as “the depiction of a wined god battling against a horned snake or standing on a lion” (Eggler and Uehlinger, 16). Egyptian art styles mixed significantly with Canaanite stamp seals prior to the Iron Age and the emergence of ancient Israel.

As Egyptian power in the Levant waned around the 12th and 11th centuries BCE, scarab stamp seals were produced far less frequently. Instead, local seal traditions distinguished themselves from the heavy influence of Egyptian culture, producing conoid and high-domed stamps out of limestone (previously, seals tended to be made of a material called enstatite). Additionally, more localized art became prominent, such as caprids flanking a tree or suckling animals. By the 9th century BCE, the increasing prominence of local symbols and images throughout the Levant are indicative of “the gradual rise and consolidation of local and/or regional chiefdoms… and formalized exchange patterns” (Eggler and Uehlinger, 16). Notably, the increase in localized stamp seal styles by the 9th century BCE parallels increased urbanization and centralization in ancient Israel.

From the mid-9th century BCE onward, stamp seals throughout the region constituted a sort of common language, “displaying such commonly recognized auspicious or apotropaic entities as winged sphinxes, uraei, falcons, sun-disks, etc.” (Eggler and Uehlinger, 17). Though of Egyptian origin, such art on stamp seals indicates a distinct Syro-Phoenician character, not an attempt to synchronize Egyptian elements with local forms. Furthermore, stamp seals from the mid-9th century BCE until the destruction of Israel contain more name and title inscriptions than previous time periods.

Alongside the imagery, stamp seals with names typically included a group of the following elements: owner's personal name, the phrase “daughter of” or “son of,” the name of the father, and occasionally an occupational title. For example, one seal from Israel translates “Belonging to Shema, servant of Yarobam” (Heb. לשׁמע עבד ירבעם). Between the words “belonging to Shema” and “servant of Yarobam” is a lion facing left. Of course, because the Northern Kingdom of Israel was destroyed around 721 BCE, Israelite stamp seals ceased to exist, and they no longer played a role in regional politics.

Image in Israelite Religion: Representations of Yahweh

Archaeological and biblical sources are exceedingly clear: Yahweh played a central role in ancient Israelite religion. That is, although Israelites recognized the reality of other deities, they were perceived as being less powerful than Yahweh. What is unique to Israel, though, is how they represented Yahweh in art, or rather, how they did not.

Throughout Syria after the 10th century BCE, anthropomorphic representations of deities became less common. That is, deities were not represented like humans as frequently as before. Rather than representing deities as humans, artists regularly represented them as animals (bull, horse, caprid), natural entities (tree), or astral symbols (crescent moon, sun disk). For Israel, this implies that they did not create images of Yahweh as a mighty warrior, fertility, or storm deity; rather, animals or astral symbols may have symbolized the deity. Referring to the Israelite stamp seal in the previous section, the lion may symbolize Yahweh; however, the lion may also symbolize a wide variety of other things: kingship, the owner of the seal as mighty, an apotropaic image, and more. We have no way to confirm. What we know for sure, though, is that in ancient Israelite art Yahweh is not represented anthropomorphically.

Ritual, Cult, & Art in Israel

Another significant place where art appears in ancient Israel is in cult areas. One of the most famous artistic artifacts related to an Israelite cult is a cultic stand from Taanach. Standing at almost 1 meter tall, it has four tiers and a roof. Each tier contains religiously inflected art. For example, the third tier contains two caprids facing and climbing a stylized tree; the tree symbolizing a goddess or fertility. Likewise, the lowest tier contains what historians Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger call the “Mistress of the Lions,” influenced by Phoenician art and reflecting the worship of a goddess (157).

Interestingly, the second tier contains “only a pair of cherubs and a space and no depiction is missing between them… The space appears to have been left empty intentionally” (Keel and Uehlinger, 157). Because Cherubs (Hebrew plural cherubim) were considered divine guardian creatures, two possibilities could explain the blank space. First, the blank space could be emblematic of an “invisible deity.” As previously mentioned, anthropomorphic representations of deities decreased in the 10th and 9th centuries BCE. Such an interpretation of the blank space is reminiscent of biblical texts. In Exodus 25:19-22, Cherubs are attached to the top of the ark. The ark is representative of Yahweh's footstool. Even so, Yahweh is not represented by any image. Thus, there is a resemblance between the representation of Yahweh in biblical texts and Israelite art.

Another interpretation is that the Cherubs flanking blank space is symbolic of Cherubs guarding the entrance to a shrine. Similar notions are evident in Neo-Assyrian art and architecture, where the massive Lamassu guarded the entrance into the king's palace. In conclusion, whether the art represented Yahweh as an “invisible deity” or the entrance to a shrine, Israelite art was clearly used to enrich cult contexts, the symbols of divine entities and images conveying a degree of sacredness and communicating to the audience, demarcating the area as sacred, and creating a space for Israelites to practice their religious rituals.

Conclusion

The Kingdom of Israel created and received art as part of social activity. Though their art forms and motifs were not particularly unique in and of themselves, what was unique is how the art was used to bolster ancient Israel's legitimacy in relation to other powers. Israel displayed art to demonstrate its power (Samaria ivories), participate in regional politics (stamp seals), express religious ideas, and create sacred spaces for cultic rituals. Simply put, the Kingdom of Israel used art in order to communicate ideas among themselves and to others.