Technology enabled ancient Israel, the Northern Kingdom excluding Judah, to be economically prosperous and establish itself as a major political power as early as the 10th century BCE, steadily growing until its destruction in 720 BCE. Some of the most important technologies evident in archaeological and literary records include, though are certainly not limited to, construction and architecture, writing, industrial tools, and weapons of war.

As ancient Israelite technology here is presented primarily from the historical timeline as derived from archaeology, not the Hebrew Bible, the chronology suggested by Z. Herzog and L. Singer-Avitz will be used. Likewise, for the sake of this definition, “Israel” and “ancient Israel” refer to what is traditionally called the Northern Kingdom, while “Judah” refers to what is traditionally called the Southern Kingdom, with reference to the Hebrew Bible. “Israelite” or “Samarian”- Samaria being the capital of ancient Israel - and “Judean” or “Judahite” refer to the people of Israel and Judah respectively.

Technology in Israel Between the 13th and 11th Centuries BCE

The earliest mention of Israel appears in the Merneptah stele, which suggests that all the Israelites were killed. This was likely Egyptian propaganda. Even so, archaeological evidence for Israelites in this region as a unique ethnicity is lacking during this period. Therefore, is too hypothetical to discuss Israel's technology prior to the 10th century BCE.

Town Building & Fortifications

During the Early Iron IIA (c. 950-900 BCE), settlements were small and unfortified, often lacking large public structures. In the Late Iron IIA (c. 900-840/830 BCE), the amount of large public architecture increased: construction of residencies/palaces, large royal enclosures, high places, and fortifications with walls and gates. Construction of such structures by the political elite is reflective of social and cultural changes, especially the increasing centralization of power in ancient Israel.

Though Arameans subjected Israel to regular incursions and attacks between the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the Neo-Assyrian king Adad-Nirari III subjugated Damascus in the early 8th century BCE. As a result, Israel experienced territorial growth and economic prosperity because it was putting less resources into defending territory. Israel's architectural infrastructure grew dramatically: extensive city fortifications in places like Dan, Megiddo, and Hazor; monumental city walls; multi-towered city walls; and multi-gate entryway systems. The Golden Age of Israel lasted until the mid-8th century BCE.

In response to Israel's revolts against Neo-Assyria, Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II (and/or Shalmaneser V) destroyed Israel's large, well-fortified settlements (733/732 BCE; 722/721 BCE). They also deported thousands of inhabitants of Israel. In other words, Neo-Assyria swiftly eliminated the technologies, namely the structures, which had enabled Israel to thrive during the 9th and 8th centuries BCE.

Writing

Though we often take it for granted in the modern period, writing – even the words in a paperback book – is a technology:

Writing is a 'machine' to supplement both the fallible and limited nature of our memory (it stores information over time) and our bodies over space (it carries information over distances).

(“Writing as technology,” Oxford University Press Blog).

Therefore, writing plays an important role in understanding technology in ancient Israel, a technology enabling political centralization, expanding economic potential, and contributing to the development of a scribal social class.

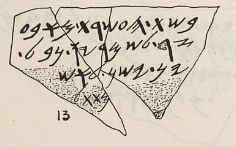

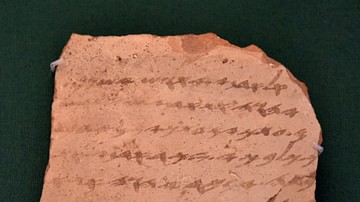

The most significant evidence for writing in ancient Israel was discovered in 1910 CE. G.A. Reisner excavated at Samaria, the capital of Israel during the 9th and 8th centuries BCE. He uncovered 102 ostraca (potsherds with writing) written in the Hebrew language. The ostraca are dated from about 865 to 735 BCE, coinciding with ancient Israel's Golden Age. Of the legible and readable ostraca (63/102), all of the texts are receipts “recording the transmission of luxury goods”(Noegel, 196).

For example, one ostracon describes the shipment of wine: “In the ninth year (of the king): from (the district of) Qosah, to Gediyahu: a jar of aged wine” (Noegel, 196). Another text is less clear about the materials send and received: “In the fifteenth year (of the king): from (the district of) Heleq to 'Asa' (son of) 'Ahimelekh, Heles from (the district of) Haserot” (Noegel, 197). Though the texts are relatively uninteresting, they provide insight into how ancient Israel used writing as a technology for economic and political purposes.

First, writing enabled the political leaders in Israel to keep records of and collect taxes. Subsequently, Israel could pay its required tribute to the Assyrian Empire and develop industrial and war technologies. Second, writing enabled more regular communications between settlements in Israel, resulting in a more defined Israelite ethnic identity. Third, writing resulted in a scribal social class. Although texts within the Hebrew Bible are primarily written from a Judahite perspective, various scholars conjecture that texts like Hosea, Amos, and the Elijah-Elisha narrative in Kings developed out of oral or written traditions from Israel after the destruction of Samaria and migration of Samarians (Israelites) to Jerusalem.

Industry

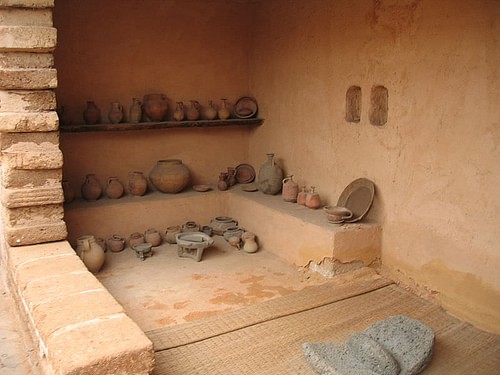

From the 10th century BCE until the 8th century BCE, Israel was involved in multiple industries, each utilizing different technologies. Here we will focus on two major industries. First, Israel boasted “the largest centers for the production of olive oil in the region”, growing significantly in this period (Faust 2015, 778-779). Archaeologists Zvi Gal and Rafael Frankel describe a type of olive-oil press discovered around Galilee, dating to the 8th century BCE: “This press consists of a round, free-standing crushing mortar… and a round-cut press bed… of the same diameter. The oil was collected in a lateral rock…” (1993, 130). A different type of olive press was used at Dan, where scholars have suggested that “stones were most likely used as counterpoise weight for a beam or lever press” (Stager and Wolf 1981, 96). In other words, Israel used at least two types of olive-press technology in order to press olives, create olive oil, and use it themselves or sell it to neighbors.

Second, Israel was involved in the wine production industry. For this, they constructed wine presses next to vineyards. The installations consisted of large, shallow basins. First, grapes would be placed in the basin. Then, individuals would press the juice out of grapes by stomping on them. Finally, juice would flow towards a lower basin, wherein it would be collected into jars and stored. A good example of this technology is present at Tell en-Nasbeh, which Israel may have occupied in the 10th century BCE.

The technology of ancient Israel, namely wine and olive presses, enabled them to leverage the natural resources of the land and more actively participate in the regional economy. As a result, they became more prosperous. Moreover, texts from the 9th and 8th century attest to the large amount of wine and olive oil shipped within, into, and out of ancient Israel, as mentioned previously in the Samaria ostraca. Unfortunately, the destruction of Samaria and many Israelite cities and towns in the 8th century BCE resulted in the destruction of technologies which, for so long, had enabled Israel to be prosperous.

Horses & Chariots

One of the most significant technologies used by Israel was chariots. According to a propaganda text from King Shalmaneser III of Assyria describing a coalition of Israelite, Aramean, Phoenician, and other regional powers from the Levant, Ahab, the king of Israel, contributed 2,000 chariots to the coalition in 853 BCE, fending off Neo-Assyrian powers from expanding closer to the Mediterranean Sea. Such a number is further notable because M. Elat suggests that “Israel's chariot force alone was equal to that of the Assyrians” (35). Put another way, Israel's use of military technology, both in the form of horses and chariots, enabled it to become a major regional power in the 9th and 8th centuries BCE.

The prowess of military chariot technology of Israel lasted well into the 8th century BCE, supported by archaeological excavations at Megiddo of many horse stables dating to the same period. Even after the defeat and deportation of Israelites in 720 BCE, Assyrian records specifically mention a unit of Samarian charioteers. This shows that entities outside of Israel recognized the strength of Israel chariot technology and their ability to use it.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, Israel used more technologies than the above; technologies used by many groups during the Iron Age. However, those that enabled Israel to grow economically and develop as a powerful force in the ancient world occurred were city building, writing, industrial technologies, and chariots. Although some Israelites remained in northern Israel after 720 BCE, the wave of destruction throughout the region resulted in seismic cultural and social shifts, as the Kingdom of Israel ceased to exist as a political power.