Italy occupied Ethiopia for five years, from 1935 to 1941, following a mass-scale invasion launched by the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (1883-1945). However, Ethiopia had been a long-aimed colonial objective of Italy, which had already tried to invade the country in 1896 but was eventually defeated at the Battle of Adwa. Mussolini was determined to show that fascism could avenge the humiliation of Adwa and realise the dream of a new empire for Rome.

The First Italo-Ethiopian War

In the first half of the 19th century, Ethiopia was nominally an empire but actually fragmented into several lordships. Only thanks to the military campaigns led by the Negus Neghesti (emperor) Tewodros II (1818-1868) and Yohannes IV (1837-1889) was imperial power extended and consolidated. But while the Ethiopian monarchy was still trying to unify the country, the European powers were launching themselves into the colonisation of Africa, starting the so-called 'scramble for Africa'. A few decades later, in 1914, only two African states were still independent: Liberia and Ethiopia.

In the context of this new wave of imperialism, a private purchase of the bay of Assab was the first step that led to Italian colonialism in Eritrea. The young Italian kingdom, united in 1861, was not ready to engage in a colonial invasion, but under the pretext of a private concession, it could set foot in Africa without being directly involved. Only in 1882 did Italy formally take control of Assab, thus beginning a more proactive phase: in 1885, Italian troops occupied the city of Massawa, a port on the Red Sea, with the aim of gradually expanding Italy's colonial possessions at the expense of the Ethiopian Empire.

At the time, however, Yohannes IV was facing internal turbulences and a war on the frontier with Sudan, where a group of rebels called Mahdists revolted against the Ottoman-Egyptian rulers, supported by Ethiopia. Ras Alula (1847-1897), one of the most powerful Ethiopian military leaders and governor of the province where Italian troops had started the offensive, decided to respond and annihilated in Dogali a battalion of 500 Italian soldiers on 27 January 1887. Even though the attack was not ordered by the Negus, Italy decided to launch a military expedition against Ethiopia. Despite the mobilisation of 20,000 soldiers, the war took an unexpected turn. Yohannes decided to withdraw his army, which outnumbered its Italian counterpart, prioritising the border war with the Mahdists instead. The emperor died at the Battle of Gallabat in 1889 against the Mahdists, marking the end of the Ethiopian involvement in the war.

The death of Yohannes IV brought a fight for succession between the natural son of the emperor, Mengesha Yohannes (1868-1906), and the king of Shewa, Menelik (1844-1913). The latter was supported by the Italians because he tried to subvert Yohannes' efforts in the centralisation of power. Italy had also previously signed a convention with Menelik in 1887, which guaranteed Menelik a supply of weapons in exchange for his neutrality towards the Italians. Menelik was quicker than Mengesha to win the support of the Ethiopian nobility and clergy, defeated his rival militarily, and was crowned in 1889.

In the same year, before Menelik's coronation, the Treaty of Wuchale had been signed, which aimed to promote good relations between Italy and Ethiopia. However, the treaty would cause a clash between the two countries. The misunderstanding, whether intentional or not, derived from a difference in the interpretation between the Amharic and Italian translations of Article 17, which concerned international diplomacy. It was not uncommon to include a clause in international treaties that allowed one party to act as an intermediary on behalf of the other, and signing the treaty, Menelik simply wanted to further improve relations with the Italians, using them as middlemen in relations with other European powers. On the other hand, Italy claimed that the treaty established a protectorate over Ethiopia, as if the Negus had accepted to cede his sovereignty in foreign policy to the Italian government.

At that time, the Italian prime minister, Francesco Crispi (1818-1901), was strongly advocating for a more important role for Italy amongst the great powers. His unscrupulous foreign policy combined an increasing militarisation with colonial activism. In this regard, Crispi was the first one to provide a justification for Italian expansionism, namely the necessity to combine expansionist policies with emigration. In those years characterised by a mass migration of southern Italians to the north of Italy, Africa could provide an alternative source of land for poor farmers. The link between colonialism and emigration would be resumed later by fascism, with its leader Benito Mussolini emphasising the search for 'a place under the sun' for Italy.

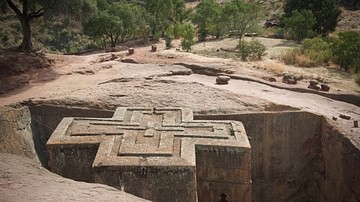

In 1890, Crispi officially instituted the Eritrean Colony, with Massawa as its capital. Menelik was able to avoid any interference from Italy, and in 1893, he denounced the Italian claim of a protectorate over his empire. Italian control had expanded to the cities of Asmara and Cheren, and its influence was projected inside Ethiopia, in the region of Tigray. The new governor of Eritrea, general Baldassarre Orero (1841-1914), was so confident of the weakness of Abyssinia (as Ethiopia was frequently referred to) that he decided to march towards the city of Adwa, which held a particular religious importance for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the main denomination in Ethiopia. For this unauthorised initiative, Orero was dismissed and replaced by General Antonio Gandolfi (1835-1902), and then by a close friend of Crispi, Oreste Baratieri (1841-1901). Baratieri's ambitions, however, were bigger than the troops at his disposal, and he provoked the powerful neighbour with several military expeditions beyond their border. The new governor believed that, with a quick occupation of Tigray, he could threaten the stability of the Ethiopian Empire, and in 1895, he began the invasion.

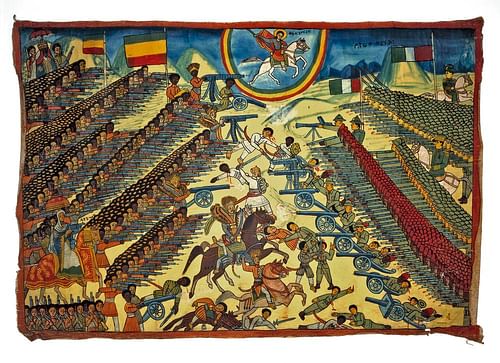

The situation quickly got out of hand: the Ethiopian leaders allied with Italy withdrew, confusion reigned among the military commands, and the Italian troops began to suffer significant losses. General Baratieri had decided to launch a surprise attack against the Ethiopian positions, but the three Italian columns were unable to coordinate their efforts, and one of them got isolated due to imprecise maps. On 1 March 1896, at the Battle of Adwa, Italian troops were heavily defeated, with around 6,000 deaths and more than 3,000 soldiers captured.

It was the worst defeat of a European army in the whole history of colonialism. What followed was a political earthquake: Crispi's cabinet collapsed, and Ethiopia secured decades of full sovereignty. The battle became a symbol for Africans and a collective trauma for Italy, paving the way to revanchist sentiments that culminated with the fascist invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.

Ethiopia between Menelik II & Haile Selassie

The Ethiopian victory increased the international prestige of the empire. Menelik, in fact, secured a series of treaties with foreign powers between 1897 and 1905. At the same time, the Negus promoted modernisation of the Ethiopian economy, opening, for instance, the first section of the Addis Abeba–Djibouti railway, which aimed to connect Ethiopia to the Red Sea. Modernisation proceeded in parallel with the consolidation of the imperial power at the expense of peripheral regions, such as Tigray, fighting for more autonomy. Ethiopia deepened its ties with France and Great Britain and became the first African state to be admitted to the League of Nations in 1923.

However, as Menelik's health started to decline from 1906, succession to the Ethiopian throne drew the attention of international diplomacy. France, the United Kingdom, and Italy signed a treaty in 1906 (the 'Tripartite Treaty'), which established three areas of influence within Ethiopia. Italy considered this a step back from the position of its supposed preeminence in Ethiopia pre-1896. Only in 1909 did the Negus choose his heir, namely his young grandson Iyyasu (1895-1935), who had to wait in a long limbo until the death of Menelik in 1913 to ascend to the throne.

Iyyasu's rule was characterised by many contradictions. The most controversial aspect was his benevolent attitude towards Islam, which was depicted by his opponents' propaganda as a scandalous proof of apostasy from his Orthodox Christian belief. Iyyasu, accused of converting to Islam, was deposed by the nobility and was substituted by his aunt Zewditu (1876-1930), with the contextual proclamation of her cousin Tafari Makonnen (1892-1975) as Ras and designated heir. This uncommon double designation left space for many ambiguities in the prerogatives and the boundaries between the two royals. Moreover, Ras Tafari had always acted as if he were the regent and not only the heir to the throne, overshadowing the empress. Zewditu and Ras Tafari also had different cultural and political experiences, and the prince was able to disband any internal resistance to his power. With the death of Zewditu in 1930, the coronation of Ras Tafari as Emperor Haile Selassie I, therefore, only represented a formality and paved the road for a new centralising outlook in Ethiopian internal policy.

Italy & the Preparation for the War

It is not surprising that, after the First World War (1914-1918), Italy was advocating for a revision of the status quo in the Horn of Africa. The German Empire was defeated, and the winners, especially France and the UK, were interested in splitting the remains of Germany's colonial possessions. The Italian Ministry of Colonies worked towards the enlargement of the Italian Somaliland and the control of both the railway and the Bank of Abyssinia, thus economically controlling Ethiopia. However, the exorbitant requests that Italy had for its colonies were soon ignored by the other powers. Besides the colonial claims, the peace conference was fruitless for Italy, and the frustration for the vittoria mutilata (mutilated victory) shaped the political discourse in the Italian public opinion, being then exploited by fascist propaganda.

With the rise of fascism from 1922, old ambitions started to be paired with a more aggressive policy. The main result was an exchange of letters between Mussolini and Ronald Graham (1870-1949), British ambassador in Rome, remembered as the 1925 Anglo-Italian agreement. Thanks to this exchange of notes, Italy obtained the recognition of its influence in northern Ethiopia. The agreement was intended to remain secret but became public, creating a diplomatic incident. France, which was part of the 1916 agreement, was outraged by its exclusion, and Ethiopia lamented the imperialist implications of the treaty, contrary to the spirit of parity between the member states of the League of Nations.

Nonetheless, Mussolini could secure a rapid rapprochement with Ethiopia, as demonstrated by the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the two countries signed in 1928. The treaty and the peace did not last long. The diplomatic line was opposed by those who were in favour of a subversive approach. The final push towards a military solution came from a mix of internal and international factors. Mussolini wanted to dismantle the shaky post-WWI order established by the Treaty of Versailles, which was already threatened by the rise of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) in Germany. Moreover, the war, unjustifiable under any economic pretext, was intended as a tool to consolidate the national prestige of the Duce.

The casus belli was the incident of Walwal (1934), a small fort along the border between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland. A clash between Italian and Ethiopian troops became the pretext for Italy to claim disproportionate reparations. But before launching the invasion, Mussolini sought the crucial acquiescence of France and Great Britain. Both Britain and France believed that the main risk for the post-war equilibrium was Hitler and not Mussolini, so they were favourably disposed to pleasing the Duce. In January 1935, the Duce met Pierre Laval (1883-1945), the French minister for foreign affairs who believed in the necessity to co-opt Mussolini in a cordon sanitaire against the activism of Nazi Germany. The two signed a treaty that, besides some minor territorial adjustments in Africa, gave Mussolini free rein in Ethiopia. On the other hand, the British silence on the topic at the Conference of Stresa (April 1935) and during the visit of the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden (1897-1977) in Rome (May 1935) was interpreted as a tacit consent.

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War

On 3 October 1935, without a formal declaration of war, Italy started the invasion of Ethiopia from the two colonies of Eritrea and Somalia. Italy was soon denounced by the League of Nations; it was condemned and sanctioned. However, the sanctions were completely ineffective. For instance, the sanctions did not include oil or steel, fundamental to weakening any military initiative. The invasion of a member state of the League by another member was evidence of the weakness and ineffectiveness of this international body in ensuring collective security. Without any army at its disposal, the League could not enforce its decisions. At this point, only Great Britain could have stopped the war. The British fleet, with its striking superiority in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, could have easily stopped the deployment of men and weapons. But the British cabinet continued with its stubborn policy of appeasement, trying to find a compromise that would have ultimately seen the dismemberment of Ethiopia anyway.

Mussolini put all his personal and political weight behind the success of the campaign, and no failures that could undermine his prestige were admitted. The commander-in-chief of the war, General Emilio De Bono (1866-1944), was accused of proceeding too slowly and was substituted with Marshal Pietro Badoglio (1871-1956). Badoglio was authorised to use mustard gas in the war, which had been banned by the 1925 Geneva Convention. Leading the operations from the south was General Rodolfo Graziani (1882-1955), already known as the 'Butcher of the Fezzan' for his role in the Italian colonisation of Libya. Despite having received the order to attain a more defensive position, Graziani decided to conduct a second offensive from the south. However, he proceeded more slowly and with more losses than Badoglio, who entered the Ethiopian capital, Addis Abeba, while Graziani was still stuck before Harrar.

The first phase of the war was followed in January 1936 by a counteroffensive. However, the lack of coordination between the military commands weakened the Ethiopian front, leading to its defeat at the Battle of Tembien on 20-24 January. Following the breach of the Ethiopian counteroffensive, Italian troops stormed Amba Aradam, flown over by the air force. Thanks to its numerical superiority, the Italian army defeated its smaller Ethiopian counterpart at the Second Battle of Tembien at the end of February. The epilogue of the war happened in Maychaw on 31 March 1936, a pitched battle in which the Negus had placed all his last unfulfilled hopes.

Ethiopian Defeat & Italian Colonialism

The Italian advance was due to both the technical superiority and the colossal number of people deployed for the war. Ethiopia suffered the consequences of the long-lasting embargo on weapons, resulting in a total number of modern armaments and ammunition way inferior to their counterpart. The most striking difference, however, was in the air force: the Negus could only count on eight functioning aircraft, while Italy deployed 400 planes. In addition, Mussolini did not want to risk being outnumbered as it had happened at the Battle of Adwa, so he organised a mass expedition of armed forces, corroborated by the presence of the Askaris, the colonial troops recruited all across Italian colonies. It was the complete reversal of the situation at the Battle of Adwa, when Ethiopians outnumbered the Italians. Furthermore, the Ethiopian army (and society) was in the process of switching from a feudal structure to a centralised organisation. The steep modernisation of Ethiopian administration, accompanied by a long period of military disengagement, demanded more public servants than military leaders.

On 5 May, Mussolini proclaimed the establishment of an Empire for Italy. That included Eritrea, Somalia, Libya, and Ethiopia, forming a new entity called the Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI, Italian East Africa). The first viceroys of the AOI, Badoglio and Graziani, represented the peak of a violent colonial control, aimed at repressing the Ethiopian resistance. Indeed, despite the military victory, Italy could never fully secure its control over Ethiopia; its influence was confined to the urban areas. Italians faced a nationwide resistance movement, the Arbegnoch, which engaged in guerrilla warfare against the occupation.

The most famous event linked to the resistance was the failed assassination attempt of General Graziani on 19 February 1937. Graziani responded with a brutal backlash; for three days, Addis Abeba was bloodied by thousands of indiscriminate killings against the population. The repression was extended beyond the capital to bend the Ethiopian élites, as in the extermination of the Coptic clerics of Debra Libanos between 21 and 29 May 1937. The policy of terror was scaled down when Mussolini replaced Graziani with the new viceroy Amedeo di Savoia-Aosta (1898-1942), cousin of the king, who tried to introduce a colonial administration more akin to the British model of indirect rule.

However, the Duke of Aosta could not avoid the diktats coming from Mussolini, pushing for racial segregation between Italians and Ethiopians, banning, for instance, mixed marriages. Ethiopia became the cornerstone of the policy of settlement of Italian poor farmers. But meanwhile, the operations carried out by the resistance, even if characterised by a lack of cohesion, were fundamental in corroding the Italian control over Ethiopia, offering a weakened adversary to the British when they launched a military operation against Italian colonies in 1941, marking the end of five years of Italian occupation.