Izumi Shikibu was a writer, poet, and member of the Japanese court during the Heian Period (794-1185 CE). Her birth date is variously given as sometime in the 970's CE, and she died in the 1030's CE. In her celebrated memoirs, known as the Izumi Shikibu Diary, she recounts episodes from court life and her affairs with two princes. The diary includes many of Izumi Shikibu's poems, which are regarded as amongst the finest ever written in Japan.

Biographical Details

Izumi Shikibu was the daughter of a minor court official, Oeo no Masamune, and herself became a low-ranking member of the Japanese imperial court, specifically the entourage of Shoshi (aka Empress Akiko), the wife of Emperor Ichijo (r. 986-1011 CE). The group of court ladies included another famous writer: Murasaki Shikibu, who wrote the Tale of Genji, considered by many the world's first novel. The purpose of assembling such a talented group of ladies to tutor and amuse Shoshi was to ensure she, a representative of the powerful Fujiwara clan, maintained favour with the emperor and so safeguarded the clan's influence.

Izumi Shikibu's name derives from the job of her father and husband. Shikibu means 'secretariat', which was the role of her father as in ancient Japan it was common to call a daughter by her father's position. Izumi Shikibu married a man of similar rank to her own, Tachibana no Michisada, the governor of Izumi, with whom we know she had a daughter, Koshikibu (herself a noted poet), and hence she adopted the name Izumi.

Her poetry is of the waka style, that is, each poem has precisely 31 syllables in five lines (5+7+5+7+7). Like those of her contemporaries, the poems emphasise sadness and the temporary nature of people's lives and loves. This approach was based on experience for when her lover Prince Atsumichi died, the poetess considered retiring to a monastery as she stated in the following preface to one of her poems: "Composed about the same time, when I was thinking of becoming a nun." The poem runs:

I feel so wretched

I am ready even to

Abandon the world -

When I think that I was once

Intimate with such a man!

(Keene, 297)

Following a year of mourning, the writer met and married the military official Fujiwara no Yasumasa (958-1036 CE). When Yasumasa relocated to the provinces, Izumi followed him. It seems that towards the end of her life, in the 1030's CE, Izumi Shikibu turned to Buddhism, as the following poem illustrates:

Coming from darkness

I shall enter on a path

Of greater darkness,

Shine on me from the distance,

Moon at the edge of the mount.

(Keene, 288)

Here, the 'path' is a spiritual journey and the Moon a common metaphor for Buddhist enlightenment. Indeed, there is to this day a minor cult and shrine dedicated to Izumi Shikibu at the Joshin'in, a Shingon Buddhist temple in Kyoto, which is also the site of her (alleged) tomb. Every year there, on the 21st March, the traditional date of the poet's death, services are held and her texts recited.

Izumi Shikibu Diary

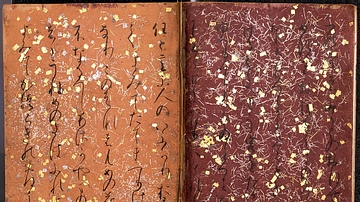

The diary of Izumi Shikibu, known in Japanese as the Izumi Shikibu Nikki and perhaps written in 1004 CE, is really not a diary at all but rather a series of memories and episodes. Written in the third person, the author refers to herself throughout as onna or 'the woman'. Although covering one year starting from the summer of 1003 CE, there are no dates for the entries and, like a work of fiction, the author imagines the thoughts of those people involved in her memories. For this reason, a minority of scholars hold that the work was not written by Izumi at all. In another departure from the pure diary form, 140 waka poems appear in amongst the prose. The poems cause the reader to pause in the narrative and enhance the presentation of love as a dreamlike experience, a common notion in Japanese literature of the period.

The diary concerns the year when Izumi Shikibu and Prince Atsumichi (981-1007 CE) had their scandalous affair, which caused the prince's wife to leave him. We also know that the year before Izumi had had an affair with Atsumichi's older brother Prince Tametaka (977-1002 CE), a relationship which seems to have ended her own first marriage. The affair ended with Tametaka's death, aged only 26, and Izumi was not to have much luck with his brother either for he died in 1007 CE. Here is a sample extract from the diary, illustrating the typical insertion of poems which often appear in pairs, one as a reply to the other:

The Prince had come in his usual secret way. Onna, thinking it unlikely that he would come and, wearied from the recent religious ceremonies, was dozing, so when there was a knock at the gate there was no one who might notice the sound. His Highness had heard various rumors and, surmising that another man might be inside, noiselessly retired and the next day there was:

While standing

before the wooden door

that was not opened

I experienced

a cruel heart.

So this is what it is like to be wretched, I now know. Look at my pitiful state. "It appears that His Highness did announce himself last night! How heartless it was for me to be sleeping!" she thought. She replied,

How can you 'experience'

whether or not

that 'heart is cruel'?

You just left untouched

my 'wooden door'.

(Wallace, 19)

Izumi's loss of her first lover, her search for consolation with the second, and the couple's fear of court gossip are the dominating themes of the diary:

…he was now living in a highly secluded place, he said. She went with him, deciding that this time she would simply do whatever he asked of her. They talked together to their heart's content from morning till night, rising or sleeping as they pleased. She felt relieved of the bitter tedium of her days and wished to go and live with him.

(Keene, 376)

Example Poems

As I lie prostrate

Indifferent that my black hair

Is all dishevelled,

I recall with yearning how

He always combed and stroked it.

(Keene, 296)

Because I planted

A cherry tree at a house

That nobody visits,

I now use the cherry flowers

To beautify myself.

(Keene, 296)

The cherry tree

In my garden has blossomed,

But it does no good:

The woman, and not a tree,

Is what draws the visitors.

(Keene, 296)

I'm still alive, yes,

But can I depend on it?

The thing that reveals

The true nature of the world

Are morning-glory blossoms.

(Keene, 296)

If only the world

Into spring and fall

We could forever make

And summer and winter

Were never more.

(Whitney Hall, 99)

For love I am ready

To change even my human shape;

All that distinguishes

me from the summer insects

Is that my flame is hidden.

(Keene, 297)

I have heard there is

A night when the dead return;

But he is no more,

And the house I live in is

A soulless habitation.

(Keene, 297)

Now I can only think -

Yes, that happened, and that, too,

Recalling the past.

I wish I had some memories

So sad I'd want to forget them.

(Keene, 297)

Soon I shall be dead.

As a final remembrance

To take from this world,

Come to now once again -

That is what I long for most.

(Keene, 298)

Legacy

The poems of Izumi Shikibu were greatly appreciated in her own lifetime. One of Izumi's poems appeared in the imperially commissioned poem anthology the Shuishu, which was completed in 1005 CE. She fared rather better in the Goshuishu, another imperial anthology, published in 1087 CE, this time having 68 of her poems included. Izumi had 16 poems in the 1152 CE imperial collection, the Shikashu, and 21 in the Senzaishu collection of 1188 CE. Izumi Shikibu's fame lasted much longer, however. In the Muromachi period (1333-1568 CE) her celebrity as a court lady and writer from Japan's Golden Age made her the subject of one of the popular short fiction works known as otogi-zoshi. Izumi Shikibu is now widely regarded as one of the foremost poets of the Heian Period (794-1185 CE). The following extract from a 20th-century CE Japanese dictionary of biographies summarises the poet's style and continuing reputation:

Her poems are passionate and free, exploding with brilliance; the wealth of her imagination is like heavenly chargers coursing the void; and her freedom of expression is rare. She must be accounted the first poetess of our land. (Cranston, 1)

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.