Jacques Necker (l. 1732-1804) was a Swiss banker and statesman who served as finance minister to King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792). He served in the king's ministry three separate times, tasked with navigating France through its dire financial crisis. Initially popular amongst the common people, Necker played a significant role in the outset of the French Revolution (1789-1799).

From humble beginnings in Geneva, Necker would become one of the most powerful men in France with his appointment as director-general of the royal treasury in 1777. Determined not to raise taxes during the American Revolutionary War, Necker kept the nation afloat by taking out foreign loans. He achieved widespread popularity by making royal finances public and became so well-loved that his dismissal on 11 July 1789 was a major catalyst for the Storming of the Bastille. He was soon reinstated but never again achieved the same levels of public adoration, as his third and final resignation in 1790 was greeted with general indifference.

Early Career

Jacques Necker was born on 30 September 1732 in the Republic of Geneva, modern-day Switzerland. His father, Charles-Frédéric Necker, was a lawyer and a native of Neumark, Prussia, who had become a citizen of Geneva in 1726 after having been elected a professor of law there. Jacques and his elder brother, Louis, were raised Calvinists and afforded an adequate education. His studies were cut short, however, when a friend of his father offered him a clerk position in the bank of Thellusson and Vernet in Paris. Although only 15, Necker accepted the position and set out for his new life in France.

Once in France, it was unlikely he would amount to much. In a nation where all the king's subjects were required by law to be Catholics, a Protestant like Necker was already at a disadvantage. On top of that, he was shy and had yet to finish his education. Yet, even at a young age, Necker was ambitious, and would not have to wait long to prove his worth. One day, the head clerk at his bank fell sick and was unable to attend an important transactional meeting. With no one else available, Necker was sent in his place, with strict orders to stick to the instructions left for him. Assessing the details of the transaction for himself, Necker decided to trust his own instincts rather than his employer's instructions during the negotiations. His gamble paid off, and he earned the bank a profit of half a million livres. Impressed, his employers soon transferred him to the bank's Paris headquarters. Barely 20, he was on the fast track to success. Necker proved an extremely adept banker. He engaged in speculation of public funds, grain trade, and British bonds during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), rapidly building his wealth in the process. In 1762, when one of the bank's partners retired, Necker was made junior partner in his place, managing the Paris branch.

Around this time, he began to court Suzanne Curchod, a pastor's daughter who had until recently been engaged to British writer Edward Gibbon (1737-1794). Necker and Suzanne were married in 1764. Two years later, Suzanne gave birth to their daughter, Anna Louise Germaine, who, better known as Madame de Staël (1766-1817) would grow up to be a famed writer, political theorist, and leading salonnière. With Suzanne's encouragement, Necker eventually left his position at the bank to seek public office. He found one in 1768, as a director of the ill-fated French East India Company, which lost its monopoly in India and went bankrupt the following year. Still, the position was a respectable stepping stone into public life, and Necker increased his self-made fortune by selling the company's ships and unsold goods. With between 6-8 million livres capital, he then began making loans to the French government.

In 1773, Necker marked himself as a prominent voice in the finance world with his defense of state corporatism disguised as a eulogy for Jean-Baptiste Colbert, a minister during the reign of King Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715). For this work, he won an award from the prestigious Académie Française. In 1775, Necker attacked the economic theory of physiocracy, specifically criticizing Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot, the Controller-General of royal finances. Necker disagreed with Turgot's laissez-faire policies such as the removal of a controlled price on the grain trade. He was vindicated when this exact policy led to the Flour War bread riots of 1775, which preceded Turgot's dismissal the following year. Having impressed the Comte de Maurepas, the king's royal advisor, with his work, Necker was tapped as the next royal finance minister in 1777.

First Ministry: 1777-1781

Although now a royal minister, Necker's Protestant faith and commoner background still served as a liability. His appointment caused a scandal and was the subject of much gossip amongst aristocratic social circles. Barred from attending royal councils, he was also not allowed to assume the title of Controller-General of finance and was referred to as the Director-General instead. Yet, as a Protestant commoner, he was largely seen as blameless for the woes facing Catholic France, namely the faltering state of national finances. As an experienced banker, he seemed like just the man to provide a solution, the opposite of the philosophizing but incompetent Turgot. Necker was extremely confident in his own abilities and was determined to fix French finances without raising taxes.

When Necker took office on 29 June 1777, France had yet to officially join the American Revolutionary War, although a growing number of voices within the king's circle eventually made this outcome inevitable. Necker himself opposed the war, fearing the debts incurred fighting the British would push the financial crisis over the edge. When France finally went to war in 1778, Necker was faced with the monumental task of funding the conflict and fixing the Ancien Régime's existing financial crisis at the same time, all without raising taxes.

Aware that abolishing the corrupt venal offices was out of the question, lest he risk incurring the wrath of the powerful parlements, he instead abolished unnecessary offices within the ministry itself, getting rid of over 500 offices that he perceived as useless. He replaced 48 Receivers-General, responsible for collecting direct taxes, with 12 officials directly accountable to himself. Necker even went up against the Farmers-General, the powerful and much-hated agency contracted by the French government to collect indirect taxes, often by thuggish means. Although Necker would have liked to abolish the Farmers-General altogether, this was impractical in wartime. Instead, he reduced their numbers by a third and put further regulations on them.

To make taxation more efficient and more representative, Necker attempted to install provincial assemblies, bodies of the three estates within a province, whose goal was to vote on local administrative issues. He succeeded in establishing such assemblies in Berry and Haute-Guyenne, ensuring that in each assembly the representatives of the Third Estate (the commoners) were equal in number to those of the upper two estates (clergy and nobility). He tried to set up similar assemblies in other provinces but was thwarted by the king's other ministers. Already, he was making powerful enemies.

Report to the King

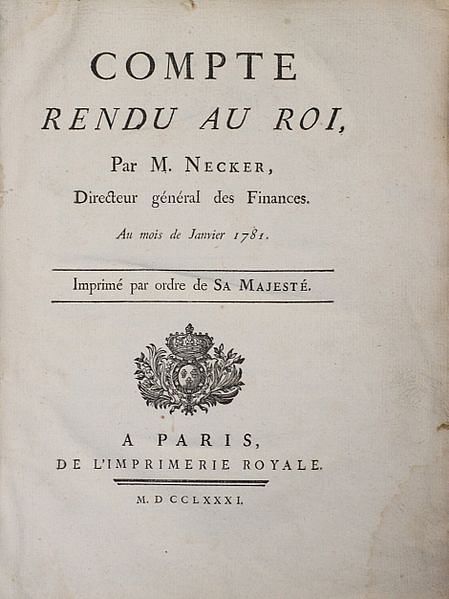

As the war dragged on, these measures were not enough, and to keep the state's finances afloat, Necker was forced to take out foreign loans. As the number of Necker's personal enemies grew, pamphlets began to circulate attacking him for mismanaging finances. In response to this, Necker made public an account of royal finances in 1781, published as the Compte Rendu au Roi (report to the king). This publication proved wildly successful and brought Necker instant fame. In a society like Ancien Régime France, where such records were historically kept private, this publication was significant. 20,000 copies were printed in Paris, an unprecedented number, which sold out in the first few weeks. The report was translated into five languages and distributed across the western world.

The Compte Rendu claimed a surplus of 10 million livres for the fiscal year of 1781, but it left out the extraordinary accounts which would have shown a deficit of over 46 million. Necker never intended this report to be misleading, as his purpose had been to demonstrate that peacetime financial obligations could be met by current income, and so excluded the loans and war debts from his figure. However, this exclusion led his enemies to claim that he had obscured the crown's true debt to make himself look better, and some labeled him as a fraud.

Necker, feeling mounting pressure from powerful enemies that included Queen Marie Antoinette, made an ultimatum to the king, threatening to resign unless he was given a seat on the royal council. Yet Necker found he was friendless; his old ally Maurepas had become jealous of his fame, and the Comte de Vergennes, the foreign minister, despised him for his criticisms of the American War. Both threatened to resign should Necker be allowed on the council, leaving Necker no choice but to resign himself in May 1781.

Second Ministry: 1788-89

The publication of the Compte Rendu had sent Necker to new levels of popularity. Following his resignation, people of all classes flocked to his home at St. Ouen, and Empress Catherine the Great of Russia (1762-1796) even invited him to attend her at St. Petersburg. Necker instead retired to Lake Geneva, where he would spend the next few years defending his time as minister, penning his famous A Treatise on the Administration of Finances in France in 1784 to justify his policies.

As the American Revolutionary War came to an end, France found that its financial crisis had indeed worsened. Blaming the situation on Necker, new Controller-General Charles-Alexandre de Calonne came up with a series of radical reforms that he hoped would save the nation from bankruptcy. In 1786, as public trust in the royal government plummeted following the affair of the diamond necklace, Necker made a glorious return to Paris; his supposed transparency with the publication of his report, refusal to raise taxes, and advocation for provincial assemblies had made him a celebrity, especially amongst the common people.

As Necker began to write venomous pamphlets critical of Calonne, Calonne himself faced issues as he tried to get his reforms passed in the Assembly of Notables of 1787. Seen as a corrupt spendthrift, the tide of public opinion shifted heavily against Calonne, who was fired in April 1787. His successor, Loménie de Brienne, did not have any better luck; his attempts at reform led to the Revolt of the Parlements (1787-88), during which time the treasury became empty. Brienne resigned in August 1788 and the king had no choice but to reinstate Necker into his ministry. With Calonne gone and both Vergennes and Maurepas dead, Necker's appointment received no vocal opposition. He accepted the position of Chief Minister of France and was finally granted a seat on the royal council. His reappointment led to fireworks and drunken celebrations in the streets of Paris.

France's future immediately looked brighter, as Necker's appointment was met with a sudden rise in the stock exchange, and his presence was seen as enough credit for the crown to secure further loans to stave off bankruptcy. To fix the financial situation once and for all, Necker announced the convening of an Estates-General, a representative body of the three estates of pre-revolutionary France with the perceived authority to administer taxation. Necker's reputation as the champion of the people was enhanced when he advocated for the Third Estate to receive an equal representation to the upper two estates, which was eventually granted.

In the early months of 1789, the Estates-General was greatly anticipated throughout France, widely seen as an opportunity for change within the oppressive Ancien Régime. So, when the Estates-General of 1789 met in Versailles in May, Third Estate deputies were disappointed when Necker's 3-hour-long opening speech stuck only to financial issues and made no mention of the social inequality.

The Estates-General soon morphed into a National Assembly, which claimed authority in the name of the people. On 17 June, the Assembly declared all existing taxes to be illegal and began working on a constitution shortly thereafter. Necker, who had intended the Estates-General to help the existing administration rather than to achieve societal reform, was nonetheless championed as a contributor to the Revolution both by the people and the king's ministers. Adhering to this reputation and the popularity that went with it, Necker did nothing to stop the Assembly's rise and offered them concessions on the king's behalf.

As part of his attempt to reassert royal authority, Louis XVI fired Necker on 11 July 1789, ordering him to leave the country immediately. The next day, the streets of Paris erupted into chaos, as rioters carrying busts of Necker broke into armories and made off with weapons. After these riots led to the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July, Louis XVI had no choice but to back down, and he reinstated Necker as his Chief Minister only days later.

Third Ministry: 1789-1790

Necker's triumphant return to Paris was treated as a festival day, though it was marred by the brutal street murder of Joseph-François Foullon (1715-1789), who had briefly replaced him in the king's ministry. In his reinstated role, Necker would serve as an effective liaison between the king the and National Assembly. He drafted Louis XVI's disapproving response to the August Decrees, which abolished feudalism, and he tried to negotiate a compromise on the topic of the king's absolute veto. When the Women's March on Versailles transferred the seat of power to Paris, Necker dutifully followed.

As it would happen, Necker's downfall came from his inability to live up to the messianic reputation that had been thrust upon him. Far from having dissipated with the outbreak of the Revolution, the nation's financial crisis had only worsened, and the treasury was empty by September 1789. Necker's attempts to battle bankruptcy through the means of creating a national bank similar to the Bank of England, and by taking out further loans both failed, and his enemies' attacks gained momentum. Jean-Paul Marat (1743-1794), in his influential newspaper L'Ami du Peuple, accused Necker of profiting off France's economic woes, going so far as to label him a public enemy; an enraged Necker put out a warrant for his arrest, forcing Marat to briefly flee to London.

The final nail in the coffin of Necker's reputation was his opposition to the assignat, Revolutionary France's new form of paper currency meant to fight the national debt. Advocates for the currency, such as Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (l. 1749-1791) argued that the economy was being stifled by the shortage of assets in circulation, while opponents such as Necker believed that the issuing of assignats would cause mass inflation and that the currency itself would soon be of no value. Mirabeau, who believed attacks against assignats were tantamount to attacks against the Revolution, accused Necker of financial dictatorship. Ecclesiastic and feudal properties were confiscated by the Assembly to back the value of the assignats, which were issued en masse in August 1790.

Necker was so opposed to this decision that he resigned on 3 September 1790. By now, his star had faded, as he exited his position amongst general indifference. Leaving 2 million livres of his own money to the royal treasury, he was harassed by angry crowds on his way home and had to ask the Assembly for police protection.

Final Retirement

Upon leaving France, Necker returned to Switzerland. Just as in France, his moderate tendencies came to haunt him, as he was seen by royalist French emigres living abroad as too revolutionary, and was viewed as too royalist by Swiss Jacobins. In 1793, after the Jacobins came to power in France, Necker was put on the list of emigres himself, and all his properties and assets in France were seized. In 1794, Suzanne Necker, who had suffered from health problems her whole life, died, leaving Necker alone with his daughter.

In 1792, he published an analysis on the trial of Louis XVI, and in 1796 he released On the French Revolution, in which he tried to explain the failures of the Constitution of 1791 and of France's constitutional monarchy. Although he had never been a republican while he was in power, Necker revealed republican sympathies in his old age, as seen in his final work Last Views on Politics and Finance. Released in 1802, this book served as a discreet plea to French First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) to establish a republic "one and indivisible, subject insofar as possible to the laws of equality" (Furet & Ozouf, 295). Napoleon, who even then was planning on establishing the First French Empire (1804-1814, 1815), took offense to Necker's last work.

Necker died on 9 April 1804, at the age of 71, and was buried alongside his wife at Coppet Castle. His legacy remains mixed; although his policy of taking out loans during the American Revolutionary War added to France's financial crisis, his Compte Rendu was itself revolutionary in making France's finances public. His commitment to the people perhaps overstated during his lifetime, Necker thrived off the popularity such a reputation afforded him. Like other French revolutionary figures, Necker's meteoric rise was followed by a similarly rapid disgrace, exemplifying the volatility and ever-changing nature of France during that time.