The 13 April 1919 Jallianwala Bagh Massacre (aka Amritsar Massacre) was an infamous episode of brutality which saw General Dyer order his troops to open fire on an unarmed crowd of men, women, and children trapped in an abandoned walled garden during a Sikh festival. At least 379 people died, and over 1,500 were injured in the massacre.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre took place in the context of violent riots in April 1919 in the Punjab and elsewhere. The British authorities had lost control of Amritsar on 11 April, and Dyer had been sent by the Governor of Bengal to restore order. Dyer was unrepentant of his actions, thinking he had displayed the necessary force to prevent a further escalation in the civil unrest that had included the murder of five Europeans. An inquiry after the terrible massacre resulted in Dyer's dismissal from the army. The massacre was one of the most infamous episodes, perhaps the most infamous in the entire history of British colonial rule in India.

Background

The British Raj (rule) of India had begun in 1858 after the British Crown and state took over the possessions of the British East India Company (EIC). The final act of the EIC had been to suppress the bloody Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-8. The acts of violence perpetrated by both sides in this rebellion against colonial rule made a deep impression, particularly on the British, who lived with a nagging fear that such an uprising could easily occur again. The British ruled over a far-from-united India. The country's divisions can be seen in political maps where Indian princely states had various degrees of dependence or neutrality. There were three great divisions in terms of religion: Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. There was also the caste system and great economic disparities between regions and peoples. The division between colonists and subject peoples was far from clear-cut, with many Indians gaining employment in the British Indian Army and the civil service. Holding on to this shapeshifting cultural melting pot was the great challenge of the British Empire. India was the jewel in the crown of British imperialism, and it was a fine balancing act to exploit India's resources without causing open rebellion.

That rebellions might occur came to be a fixation in the minds of many hardline Britishers, and there were indications that Indians were warming up to the idea of concerted and unified political action. The India National Congress had been founded in 1885, and the All Indian Muslim League in 1906. The partition of Bengal in 1905 caused much nationalist outrage (it was reversed in 1911). Following the development of mass-based politics in the first decade of the 20th century, more and more Indians were challenging the British presence in India. The Congress and Muslim League joined forces in 1916 with the Lucknow Pact, which set out what was considered the necessary constitutional reforms that would allow an independent Indian government.

Colonial tensions in India were acerbated by the First World War (1914-18). Indians had fought to protect British interests in India and abroad (in Europe, the Middle East, and East Africa), but many returning soldiers could not find meaningful employment. India had also given significant equipment and raw materials for the war effort, which highlighted more than ever the failings of the British administration. The Punjab region in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent was seen as a particularly dangerous place for British interests. The Indians of various faiths there were remarkably united and politically active, such as the Ghadar party, which dedicated itself to kicking the British out of India.

Then came the March 1919 Rowlatt Acts. Essentially, these acts allowed the British administration to continue to use the powers of control and imprisonment, which had been employed to repress protests during the World War. Indians were subject to imprisonment without cause, trial without a jury, and a range of punishments expressly designed to humiliate. On 8 April, Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), the central figure in the Indian independence movement, called for Indians to suspend work in response to the Rowlatt Acts. Many Indians followed Gandhi's call for peaceful civil disobedience, but the British stood firm and refused to repeal the Acts. There were riots, arson attacks, lootings, and clashes with police, including in Amritsar, a city in the Punjab, where a mob killed five British men on 10 April. There were other notable episodes of riots in Delhi and Ahmadabad. Gandhi was arrested, but he called for his supporters to show restraint, a plea many ignored. As a consequence of the unrest, no public gatherings of any kind were permitted.

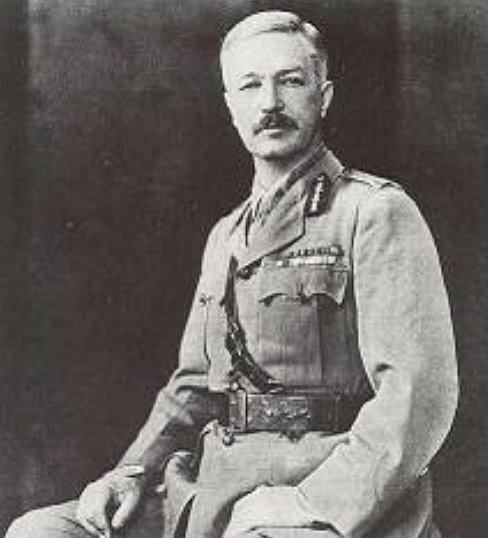

General Dyer

Brigadier-General Reginald Edward Harry Dyer (1864-1927) was an India-born career solider of Irish descent who had served in Persia and was now back on duty in India. He was 55 in 1919 and nearing the end of his career. Dyer's decision-making had already been called into question in Persia when he had acted without orders in expanding British territory there. Only ill health had saved Dyer from the ignominy of dismissal in Persia, and, transferred back to India, he was given command of the 45th Brigade of the British Indian Army at Jalandhar.

Sir Michael O'Dwyer, Governor of the Punjab, was far from sympathetic to the idea that Indians should have a role in their own governance and had already ordered the use of aircraft on rioters. Men like Dyer and O'Dwyer were beset with a paranoia that the unrest of 1919 must not be allowed to escalate to the level of the dreadful Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-8. There were, too, constant rumours and conspiracy theories that Soviet Russia was materially backing Indian nationalists to destabilise the Raj. O'Dwyer ordered Dyer to Amritsar to subdue the riots there, which had broken out on 10 April following the arrest of two prominent Indian nationalists.

On arrival in Amritsar on 11 April, Dyer witnessed firsthand the result of the riots: the looting and burning of two banks and two mission schools. Several Europeans had been killed in the violence, and one European woman, a doctor, had been beaten. The other Europeans of Amritsar had been obliged to seek refuge in the Gobindgath fort as the British lost control of the city which had a population of 150,000.

On 12 April Dyer mobilised 400 of his men and two armoured cars mounted with machine guns. In a display of force, the men marched through the streets of Amritsar, but there was no violence. On the morning of 13 April, Dyer ordered that notices be read out around the city that there was to be an immediate ban on all public meetings, processions and gatherings. Further, a curfew was to be imposed at 8 pm that day. The reading of these notices received shouts of "The British Raj is at an end." Dyer also heard news that riots were still ongoing in other Indian cities and rumours that suggested his Indian troops would not fire on Indians if ordered to. More pressing was the rumour that a large gathering was planned for that very afternoon in open defiance of Dyer's orders. The brigadier-general was likely now convinced that he must give a display of force to show the population of Amritsar that the British were back in control of the city.

A Peaceful Crowd

On the afternoon of 13 April, 15-20,000 Indian civilians gathered in the abandoned walled garden of Jallianwala Bagh, a space that, crucially, had only five narrow entrances. Many people were there to peacefully celebrate the Sikh Baisakh festival and visit its accompanying fair. Others were there to protest against the recent imprisonment of nationalists, and still others would have been passing through as it was a major thoroughfare in the city and the site of an important Sikh temple, the Golden Temple. The garden was really a sort of wasteland and provided a large open space sufficient in size to hold such a gathering of humanity. It is possible, too, that many of the crowd had not even heard of Dyer's public announcements that morning as many would have come from outside Amritsar. A British plane flying over the area convinced some of the crowd to go home.

Dyer arrived at the Jallianwala Bagh at 5 pm, and with him were his two armoured cars and around 90 men, mostly Gurkhas and Indian troops. The gateway they used to access the square was not wide enough to permit the entry of the two armoured cars, and so Dyer ordered only his infantry inside. Without giving any warning to the gathered crowd, Dyer ordered his men to begin firing into them and to continue firing. No warning shots were given. The slaughter went on for around ten minutes, during which time the soldiers had time to reload their magazines. In total, 1,650 shots were fired. Dyer had ordered his men to pick their targets and deliberately fire on those attempting to escape over the high walls of the enclosure and at the doorways. Dyer then ordered his men to leave, and no help was given to the wounded. According to the official statistics, 379 men, women, and children were killed, and over 1,500 were injured. The death toll may well have been, in reality, much higher.

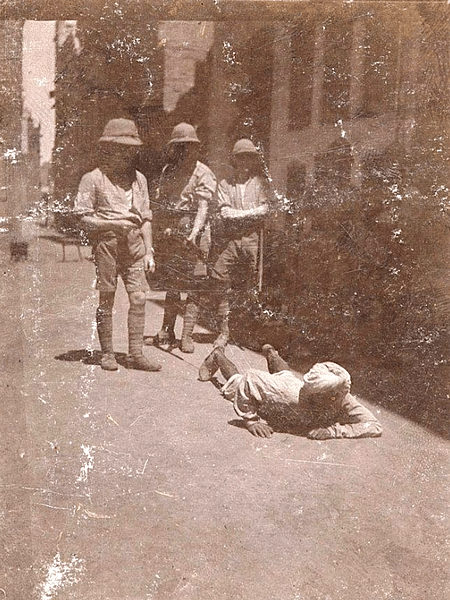

Dyer went on to order the public flogging of Indian prisoners and made any Indian man present in Kucha Kurrichhan street (where the European doctor had been beaten) crawl on the pavement in a public act of humiliation. Martial law was declared in the Punjab, and O'Dwyer ordered aircraft to bomb rioters at Gujranwala. Police brutality against the general population continued in the following months. There were 1,200 deaths, 3,600 were wounded, and 258 people were publicly flogged.

Reaction

Many Britishers, from the lowest right up to the viceroy Lord Chelmsford, believed that O'Dwyer and Dyer had prevented the unrest in the Punjab spreading elsewhere and escalating to a situation which could not have been contained. There were, though, some voices of disapproval, and these steadily grew in volume, especially when the news blackout which had accompanied martial law ended in June. A war on the Afghan frontier – which Dyer participated in – had also drawn wider attention away from the events at Amritsar. Now, at last, came the reckoning.

In November 1920, a committee appointed by the British government in London and led by Lord Hunter conducted a public hearing into the massacre. The committee met in Lahore, and its panel consisted of four British, three Indians, and Hunter himself. Dyer was cross-examined by the Indian lawyers and did himself no favours when he admitted he would have used his machine-gun-toting armoured cars if he had only been able to get them nearer the crowd. Unrepentant for any of his actions, Dyer claimed it had been the only way to prevent a rebellion or, as he put it, "to produce the necessary moral and widespread effect" that rebellion would not be tolerated (Mansingh, 201). The committee came to the conclusion that Dyer's judgement had been swayed by his own racism towards Indians and possibly also mental illness. Both Dyer and O'Dwyer were merely reprimanded by the Hunter Committee for use of excessive force, as the British members of the committee were adamant that a degree of force was necessary to preserve British control in India. If the British authorities thought that the committee's findings would end the matter, they were entirely wrong. The rumblings of outrage continued. Chelmsford changed his tune and advised King George V (r. 1910-1936) that perhaps Dyer should not, after all, be held up as the heroic defender of the British Empire. Dyer was given six months' leave, and he returned to England.

At the same time, the relatively young Indian Independence movement realised that Amritsar could provide a great push forward in its support. Nationalists, a good number of whom were trained lawyers who had meticulously gathered evidence of the massacre, now had yet another awful example of British colonial rule with which to convince Indians that they would be far better off ruling themselves, what became known as 'home rule'. The nationalist movement had clearly swung from merely criticising British institutional racism and snobbery and the drain of India's wealth to criticising the very presence of Britain in the subcontinent. More than a year after the event, the massacre had become a major story and a pivotal event in Indian-British relations.

The British establishment in London was shocked at Dyer's callous behaviour and subsequent attitude when the full story came out. Legislators who fully realised that one cannot rule by force alone struggled to understand what had motivated the general. Dyer himself told a journalist in England: "I had to shoot. I had thirty seconds to make up my mind what action to take and I did it. Every Englishman I have met in India approved the act, horrible as it was" (James, 478). The establishment, though, at least in public, was turning against him, despite the House of Lords voting in his favour. Dyer was ordered to resign from the army and strongly encouraged to retire. The British press, in contrast, largely supported Dyer. The Morning Post even raised a fund for Dyer, which was remarkably popular, receiving donations from all sorts of people from Northumberland farmers to the author Rudyard Kipling. Many thought that Dyer had indeed acted with unusual decisiveness to protect the British Empire and that he had been made an unfair example of by bureaucrats who had no idea of colonial realities on the ground. Dyer was not the villain of the empire, he was its saviour, so the story went. The fund gathered a handsome £26,000 for Dyer's retirement (over $1 million today). In contrast, the British government eventually awarded each family of victims of the massacre a mere £37 ($1600).

The End of an Empire

Indians remained outraged at the massacre. The celebrated Bengali author Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was so disgusted that he sent back his knighthood. Even some of the pro-British rulers of the independent princely states like the Raja of Nabha voiced their disapproval of Dyer's excessive use of force. The fantastic pension 'reward' for Dyer shocked many Indians more than the massacre itself. It was now impossible to blame the events on a rogue soldier who had exceeded his orders. As the future prime minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) noted: "I realized then, more vividly than I had ever done before, how brutal and immoral imperialism was and how it had eaten into the souls of the British upper classes" (Tharoor, 173). Further, the failure of the Hunter Committee to find anyone guilty of anything when there had obviously been so much unnecessary violence and acts of humiliation in the Punjab in 1919 illustrated all too clearly that the British administration had whitewashed history. Above all, the non-cooperation movement led by Gandhi was now able to draw on a much wider base of support and continued from 1920 to push for 'home rule'. Indians of all classes took a far more active role in persuading Britain by whatever means necessary that it must grant independence, an achievement finally made in 1947. As the historian S. Mansingh notes, "Jallianwala Bagh became the beginning of the end of British rule in India" (201).