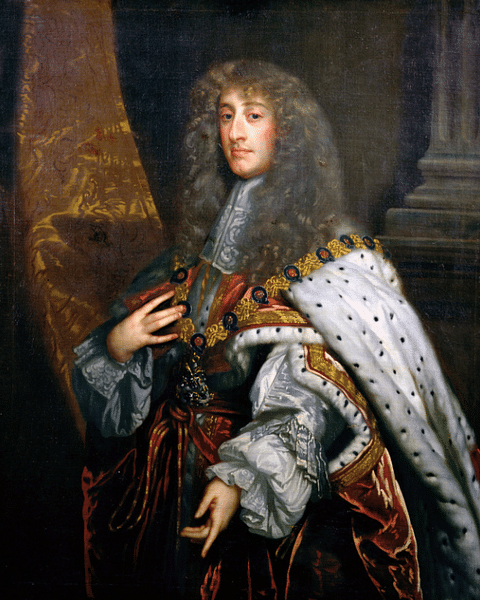

James II of England (r. 1685-1688) reigned briefly as the king of England, Scotland, and Ireland until he was deposed by the Glorious Revolution of November 1688. James, also known as James VII of Scotland, was the fourth Stuart monarch. His pro-Catholic policies were not popular, and his short reign ended when he was forced into exile. James was succeeded by Protestant William of Orange as king, and he ruled equally with his queen, Mary II of England (r. 1689-1694), the daughter of the exiled James.

A Troubled Monarchy

The British monarchy had been formally abolished during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651) when James II's father Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) was charged with treason and making war against his own people, found guilty, and executed on 30 January 1649. During the troubled conflict, Charles I had sent his family to the safety of France. Charles had married Henrietta Maria (1609-1669), the young sister of Louis XIII of France (1610-1643). The couple had nine children, the two eldest sons being Charles (b. 1630) and James, born on 14 October 1633 at St. James' Palace in London. James was made the Duke of York in 1643, and he returned to England.

Ultimate victory in the Civil War went to the Parliamentarians led by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) who ruled the new republic as Lord Protector. Supporting his father, James had been captured during the conflict at Oxford in 1646. The duke was then confined to St. James' Palace but, disguised as a girl, he managed to make his escape to the Netherlands in 1648. From there he visited his mother residing in Paris, and in 1650, he joined the French army.

The British monarchy was restored in 1660 shortly after the death of Oliver Cromwell. The Great Restoration saw Charles I's eldest son Charles take the throne as Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685). James accompanied his brother back to England and took charge of the navy as the Lord High Admiral. This was an important role given the ongoing war at sea with the Netherlands, and James was in command for a famous victory off the coast of Lowestoft in 1665. The duke was well-known for his love of hunting, horse racing at Newmarket, and his extravagant second court at St. James' Palace. It was well he had other pursuits since Parliament passed the Test Act in 1673, which effectively prohibited any Catholic from holding a public office (the 'test' was to take communion in an Anglican church and renounce the importance of the bread and wine as manifestations of Christ's body and blood, respectively). James, who had converted to Catholicism in 1668, was obliged to resign from the navy. In 1680, the king sent his brother to take charge of royal affairs in Scotland, but within two years he was back in London.

On 6 February 1685, Charles II died with no legitimate heir, and the kingdom was divided over who should succeed him. It was Charles' brother James who was ultimately chosen to continue the monarchy. He was not an entirely popular choice. Already during Charles' reign, many nobles were uneasy with James' support of Catholicism. Some politicians, who became known as the 'Whigs', called for James to be excluded from the succession, and they achieved their aim when Parliament did just that in 1679. Fortunately for James, his brother had him reinstated and so ended the Exclusion Crisis. There was, too, the practical problem of just who could take on the role if James were not king. Few wanted a return to the austere rule of Cromwell and the Puritans. James had support from the other half of Parliament, the 'Tories', who were keen not to upset the status quo and interfere once again in the natural line of succession. James II was crowned in Westminster Abbey on 23 April 1685. Hardly a young monarch at 51, James would have little time to enjoy his reign, and things started badly.

The Monmouth Rebellion

James II's main competitor for the crown had been James Scott, Duke of Monmouth (b. 1649), the illegitimate son of Charles II. Monmouth attempted to take the throne by force in July 1685. To increase his claims of legitimacy, the Protestant Monmouth claimed that his father had actually married his mother Lucy Walter, and evidence of this could be found in a mysterious black box. Monmouth's coup, known as the Monmouth Rebellion, failed as he could only muster 3-4,000 men, and this body was defeated on 6 July at Sedgemoor in Somerset by loyalists led by John Churchill, the future Duke of Marlborough. Monmouth was executed in one of the clumsiest beheadings on record that required five swings of the axe (despite Monmouth tipping his executioner six guineas to do a decent job). Many of the ringleaders were also sentenced to death, some 850 rebels were transported for a significant term of hard labour (indentured servitude) on Caribbean plantations, and anyone with even the remotest connection to the rebellion received lesser punishments like floggings. Such was the severity of the court's decisions, the cases became known collectively as the 'Bloody Assizes', and they did nothing for the king's popularity.

Family & Catholicism

James had married Anne Hyde, the daughter of the Earl of Clarendon on 3 September 1660, but she died of illness in March 1671. He married again on 30 September 1673, this time to Mary (d. 1718), the daughter of the Duke of Modena. With Anne, James had eight children, but only two survived into adulthood: Mary (b. 1662) and Anne (b. 1665), both of whom would one day reign as queen. The king had many illegitimate children and another large number of offspring with his second wife Mary, but only one lived beyond the age of 19: James Francis Edward (b. 10 June 1688).

The king played down his Catholic sympathies in the early part of his reign – he had eliminated the communion part of his coronation and, even before his succession, he had had to agree to his brother Charles' insistence that he bring his own two daughters up as Protestants. Mary of Modena, his second wife, was a staunch Catholic, and the old tensions began to appear in the kingdom again between Protestants and Catholics, with rumours abounding of the king's intentions for the Church of England and wild claims that the queen was actually the daughter of a pope.

James displayed the tone-deaf attitude so typical of the Stuart kings, and ignoring the warning signs of the Monmouth Rebellion and the rumour mill, he blithely appointed Catholics in key positions in the government, courts, navy, and army, even university appointments took on a distinct Catholic bias. The king also ignored laws, extended others, and waived sentences when they applied to Catholic individuals he favoured, what became known as his Dispensing and Suspending powers. Parliament protested at these policies, and the king responded by dismissing the House in November 1685; it would not be recalled until there was a new monarch on the throne.

There were formal measures to improve the status of Catholics such as the April 1687 Declaration of Indulgence (aka Declaration of the Liberty of Conscience), which actually improved religious toleration for all faiths, but Protestants began to fear the king was on the road to taking the country back to being a Catholic state. These fears seemed confirmed when James issued for a second time his Declaration of Indulgence in 1688 and insisted it be read out in all churches. When the Archbishop of Canterbury protested, he and six other bishops were locked up in the Tower of London to await trial. The clergymen were acquitted and crowds cheered and bonfires were lit in celebration. A group of prominent Protestants now began to explore the possibility of a replacement monarch.

Another dramatic event was the birth of Prince James in June 1688. A son would supersede the king's two Protestant daughters to the throne, and surely he would be brought up as a Catholic. So convenient was this event for the king, many suspected the child was not his own but had been brought in for the sole purpose of perpetuating Catholicism in England. The fact that Prince James' godfather was Pope Innocent XI was another unnecessary provocation. Some modern historians have been keen to question whether James really was intent on returning England to Catholicism and suggest he was merely politically naive in his methods to obtain religious toleration for Catholics.

The Glorious Revolution

Many prominent Protestants felt the time for action was now or never. The dukes of Devonshire and Shrewsbury, the Bishop of London, and others got together and contacted Protestant Prince William of Orange via the Dutch ambassador in England, inviting him to become king of England, Scotland, and Ireland. William had close connections with Britain, he was the grandson of Charles I of England and had married James II's daughter Mary in 1677. William responded favourably to the invitation – he had already been planning an invasion since the spring but was awaiting what he called a favourable "Protestant wind". William was perhaps most motivated by the danger of an increasingly pro-Catholic England joining forces with the Catholic French and attacking the Dutch navy. William had already prepared a fleet of 60 ships for his goal, allowing the English to think this was in preparation for defence against a French invasion of the Netherlands.

The Prince of Orange landed with an army of 15-21,000 men at Torbay and then Brixham in Devon in November 1688. This large force marched slowly east towards London through unfavourable weather. Meanwhile, James was left isolated, deserted by former supporters like John Churchill and even his own daughter Anne. The queen left England for the safety of France in December, and after suffering large-scale desertions and a bizarre series of nosebleeds, the king abandoned the battlefield to follow his wife. Queen Mary made it across the Channel, but the king did not, despite his disguise as a woman. He was spotted by fishermen and taken captive in Kent. William was by now in London, and he decided the best thing to do with his rival and father-in-law was to allow him to leave for France as he had wished. Once again, a Stuart king had ignored popular opinion and been ousted from his throne. The official line was that James had abdicated, and Parliament recorded the removal of the monarch as occurring on 23 December 1688, the day James had left English shores. The exiled king's arrogant attitude and lack of empathy with any other view besides his own were aptly captured by a courtier in France who said of him: "when one listens to him, one understands why he is here" (Cannon, 301).

Developments in Science

James' reign had been short, but its events were monumental in terms of history. Never again would a British monarch enjoy the powers that James had. There was a second event in his reign, and one equally dramatic in its long-term effects, this time in the field of science and physics, in particular. Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) recovered sufficiently from the blow of a falling apple on his head to present his theories of gravity in his Principia of 1687. The year before had witnessed another event of note for science, the creation of the first meteorological map of weather systems by Edmond Halley (1656-1742).

Successors & Ireland

William of Orange became William III of England (also William II of Scotland, r. 1689-1702) via a decree by Parliament on 13 February 1689. This was the first time in English history that Parliament had overseen the change of one monarch to another without bloodshed or simple hereditary convention. The event and its aftermath have been called the Glorious Revolution, even if this name is misleading since there was no popular uprising to support either James or William. If the events of 1688 were reported today, the media would likely use the term 'regime change'.

Crowned on 11 April in Westminster Abbey, William reigned equally with his queen, Mary II of England (r. 1689-1694). Their joint reign is often simply called 'the reign of William and Mary'. Some Tories wanted Mary to rule alone to preserve the purity of a hereditary monarchy, but the Whigs got their way, largely thanks to William insisting he would not take a lower position than his wife. But it was a crown at a price. Parliament was now determined to play a greater role than ever in the governance of the kingdoms of the British Isles. What became known as a constitutional monarchy where Parliament and monarch ruled in unison was established with a Bill of Rights on 16 December 1689. Parliament had gained the ultimate authority in the key areas of passing laws and raising taxes. No monarch could henceforth maintain their own standing army, only Parliament could declare war, and any new monarch had to swear at their coronation to uphold the Protestant Church. Finally, no Catholic or individual married to a Catholic could ever become king or queen again.

James II meanwhile lived in comfortable exile in France at St. Germain-en-Laye near Paris. Matters did not rest there, though. Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) encouraged James to make a bit more effort into getting his throne back. The best way back seemed to be via Ireland where the deposed king could rely on strong Catholic support. James duly landed in County Cork with a French army on 12 March 1689. Those in Ulster, the Protestant majority, were opposed to such a return. The Protestant 'Men of Orange', as they became known for their support of King William, rose to meet James' supporters on the battlefield. The Protestants survived the lengthy siege of Londonderry (Derry) in 1689, and in July 1690 at the Battle of the Boyne, they were reinforced by an army led by William in person and won a famous victory. James was obliged to flee to France for a third time in his life. In Scotland, where there was strong support for the House of Stuart, the exiled king lost the support of the MacDonald clan in February 1692 when 38 prominent members were massacred by the Campbells at Glencoe. The door was firmly closed to a return in any of the three kingdoms. James II died at St. Germain-en-Laye in September 1701. He was buried at the Benedictine Church of St. Edmund in Paris.

After William III died without an heir, James II's second daughter Anne became queen in 1702, and she then reigned over a united kingdom as Queen of Great Britain and Ireland from 1707 to 1714. Anne was the last of the Stuart monarchs and was succeeded by George I of England (r. 1714-1727), Anne's nearest relation of the Protestant faith and the first monarch of the House of Hanover. Anne's younger brother James became known as the Old Pretender since he was Catholic, claimed the throne as his, and was supported by France and the Jacobites (Stuart supporters). The Jacobite rebellion failed, though, in 1715. Another Jacobite rebellion, this time led by the Old Pretender's son Charles Edward Stuart (aka the Young Pretender or Bonnie Prince Charlie, 1720-88) in 1745 also failed, and so the British monarchy remained Protestant.