James Monroe (1758-1831) was an American statesman who served as the fifth president of the United States (1817-1825). The fourth president to belong to the so-called 'Virginia Dynasty', and the last of the generation of the Founding Fathers to hold the office, Monroe is primarily remembered for the Monroe Doctrine and the Era of Good Feelings.

Early Life & Revolution

James Monroe was born on 28 April 1758 in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the eldest son of Spence Monroe, a craftsman, and Elizabeth Jones Monroe, the daughter of a family of wealthy Welsh immigrants. James grew up on the 600-acre family farm on which he was born, and, at the age of eleven, he was enrolled in Campbelltown Academy, considered the best school in Virginia. Here, he excelled in Latin and mathematics and befriended fellow student John Marshall, future chief justice of the US Supreme Court. In the early 1770s, both of Monroe's parents died, forcing him to drop out of school to take care of his younger siblings and to look after the property he had inherited, which included several enslaved people. In 1774, Monroe was able to return to school and attended the College of William and Mary, where he became increasingly involved in Whig politics and the opposition to Parliamentary taxes.

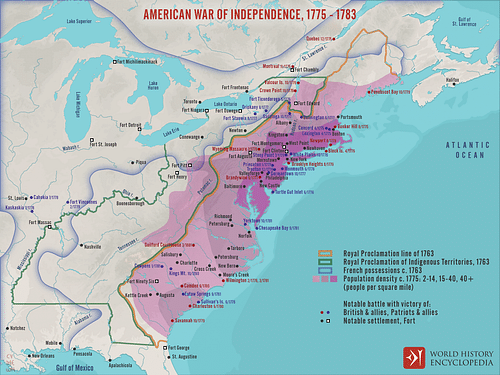

For the past decade, British Parliament had imposed a series of direct taxes on the colonies that American Whigs, or 'Patriots', had condemned as unconstitutional, on the basis that they were not represented in Parliament. The conflict had gradually escalated until, in April 1775, the American Revolutionary War broke out between Britain and the rebellious colonies. In the days leading up to the war, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, dissolved the colony's elected legislative body, the House of Burgesses, and sent British soldiers to confiscate arms and ammunition belonging to the colony's militias. Outraged, Monroe and hundreds of other Virginians followed Patriot leader Patrick Henry to the Governor's Mansion in Williamsburg, to demand the weapons' return; the conflict, later known as the Gunpowder Incident, was de-escalated when Dunmore agreed to pay the Patriots £330. Monroe, feeling this was not good enough, later broke into the Governor's Mansion with 23 other students and stole hundreds of muskets and swords for the Patriot cause.

In 1776, Monroe dropped out of college and enlisted in the 3rd Virginia Regiment of the Continental Army. That December, he crossed the icy Delaware River with General George Washington and participated in the ensuing Battle of Trenton (26 December 1776). During the battle, he was severely wounded in the shoulder while capturing a Hessian cannon and nearly died of his injuries. After recovering, he was promoted to captain for his valor and saw further action at the Battle of Brandywine (11 September 1777) and Battle of Germantown (4 October 1777). He spent the winter shivering with the rest of the Continental Army at Valley Forge, where he befriended Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, and shared a cabin with his old schoolmate John Marshall. The following year, he served at the Battle of Monmouth (28 June 1778) and was later promoted to lieutenant colonel, with recommendations from both Washington and Alexander Hamilton.

In 1780, Monroe resigned from the army and returned to Williamsburg to study law. Here, he was mentored by none other than Thomas Jefferson, who took Monroe under his wing and influenced his political development. In 1782, he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates, which he used as a stepping stone to win election to the Confederation Congress the following year. During his three years in Congress, Monroe supported the westward expansion of the United States as well as the Northwest Ordinance, which laid out the procedure whereby such lands could be admitted into the Union as states. He strongly supported the right of the US to navigate the Mississippi River – which was a point of contention with Spain – and argued against the need for a stronger central government than the one laid out in the Articles of Confederation.

On 16 February 1786, the 27-year-old Monroe married Elizabeth Kortright, the 17-year-old daughter of a prominent New York City family. Monroe retired from Congress that same year, and the couple settled in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where Monroe opened a law practice. The couple would have two daughters: Eliza (1786-1840) and Maria (1802-1850); a son, James, was born in 1799 but tragically died sixteen months later. Monroe re-entered politics in 1788 when he attended the Virginia Ratifying Convention, tasked with ratifying the newly drafted US Constitution for the Commonwealth of Virginia. Though by now Monroe agreed that the feeble Articles of Confederation should be amended, he was concerned that the Constitution left the federal government too powerful and ultimately voted against it. Nevertheless, Virginia voted to ratify the Constitution by a narrow margin, and it went into effect nationwide in March 1789, with Washington elected as the first president.

Senator & Diplomat

In 1789, Monroe ran for a seat in the House of Representatives against James Madison, another Jefferson pupil. The two vowed not to let the election sour their friendship and often traveled together during the campaign. Although Madison won the seat, Monroe would be elected to the US Senate the following year, after the sudden death of the incumbent made the seat available. During Monroe's time in the Senate, the first political parties began to form in the United States, pitting the Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton – which favored strong central government and pro-British policies – against the Democratic-Republican Party of Jefferson, which favored more autonomy for the states and supported the French Revolution. Unsurprisingly, Monroe threw his lot in with the Jeffersonians and quickly became one of the loudest critics of the pro-Federalist Washington administration in the Senate. He constantly butted heads with Hamilton, helping to expose the latter's involvement in a sex scandal in 1792; the incident almost led to a duel between the two men.

In 1794, Monroe was appointed ambassador to France. Arriving shortly after the conclusion of the Reign of Terror, he and Elizabeth were able to use their influence to secure the release of several pro-American figures who had been imprisoned by the French revolutionaries, including Thomas Paine and Adrienne de Lafayette, wife of the marquis. Yet during his ambassadorship, Monroe still proved much too sympathetic to Revolutionary France for President Washington's liking. He constantly overstepped his bounds, like when he told the French that the pro-British Jay Treaty – a trade agreement between the US and Britain that fostered warm relations between the two countries – would probably be repealed. He was recalled from his post in November 1796, with the timing being deliberate so that he would return home after the US presidential election of 1796. The following spring, Monroe retaliated by publishing a 500-page pamphlet entitled A View of the Conduct of the Executive, in the Foreign Affairs of the United States, which attacked the conduct of the Federalists and the Washington administration.

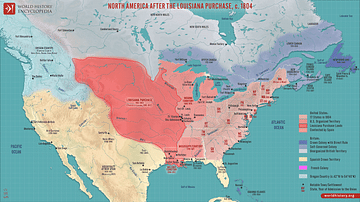

In 1799, Monroe was elected Governor of Virginia, an office he would hold until 1802. He supported the candidacy of his mentor Jefferson in the US Presidential election of 1800. After Jefferson's victory, Monroe was sent to Paris once again to help negotiate the Louisiana Purchase, which was a deal to acquire 530,000,000 acres of land from France. This was arguably the greatest achievement of the Jefferson administration, more than doubling the size of the United States. Afterwards, Monroe continued to serve the Jefferson administration as ambassador to Great Britain. In this capacity, he helped negotiate the Monroe-Pinckney Treaty in 1806 that would have extended the existing trade agreement between the US and Britain; President Jefferson, however, rejected the treaty, since it did nothing to combat the hated British practice of impressing American sailors. The administration's rejection of the treaty caused Monroe to fall out with James Madison, who was serving as secretary of state. In 1808, Monroe decided to challenge Madison for the nomination of the Democratic-Republican Party in that year's presidential election. Madison ultimately won both the party nomination and the election, with Monroe receiving little support outside Virginia.

Secretary of State

In 1810, Monroe was elected once again as governor of Virginia. But his tenure was cut short when President Madison, having reconciled with Monroe, asked him to join his administration as secretary of state in April 1811. Monroe accepted, joining the cabinet at a time when British-American relations were swiftly deteriorating. On 18 June 1812, President Madison asked Congress to declare war on the United Kingdom, beginning the War of 1812. The war went disastrously for the United States, with multiple invasions of British Canada ending in failure. Madison and Monroe were quick to blame these defeats on Secretary of War John Armstrong, Jr., leading to a rift in the administration. In August 1814, a British army invaded Chesapeake Bay and began marching toward the capital; Monroe rode out to conduct reconnaissance missions and to help organize the American line of defense at the Battle of Bladensburg. The Americans were defeated, however, and the British went on to capture and burn Washington. Armstrong was blamed for not readying the capital's defenses and was forced to resign, with Monroe taking control of the War Department in addition to his duties to the State Department.

Finally, on 24 December 1814, American and British diplomats concluded the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 by restoring pre-war borders. The treaty was ratified by Congress in February 1815, boosting the popularity of the Madison administration, which made the dubious claim that the US had won the conflict. Monroe was able to ride this popularity in 1816 when he ran for president himself. Tapping Daniel D. Tomkins of New York as his running mate, Monroe soundly beat his Federalist opponent, Rufus King, winning 134 electoral votes (King won only 34). The election of 1816 proved to be the death blow to the Federalist Party, which had fallen into disgrace for its opposition to the War of 1812; the incoming Monroe administration would, therefore, usher in a new epoch of what was essentially the single-party rule of the Democratic-Republicans. Since this brought an end to the bitter partisanship that had plagued the nation since the Washington years, the period of Monroe's presidency would become known as the 'Era of Good Feelings'.

First Term: 1817-1821

Monroe was inaugurated in Washington on 4 March 1817. A lifelong slaveholder, Monroe took several slaves with him to the White House and would keep them there for the entirety of his presidency. He and Elizabeth, influenced by their time in France, decorated the White House with French furniture and often served French food at meals; frequently ill, Elizabeth was often unable to fulfill the hostess duties of the First Lady, which were carried out by their eldest daughter Eliza. After taking office, Monroe set about building his cabinet, which included John C. Calhoun as secretary of war, William H. Crawford as secretary of the treasury, and William Wirt as attorney general. Perhaps his most significant cabinet pick was John Quincy Adams as secretary of state. A quintessential New England Yankee, Adams was chosen to appease the North and would influence much of the foreign policy of Monroe's presidency.

One such issue of foreign policy included mending relations with Britain in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The Monroe administration handled this with the Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1817, which took steps to demilitarize the Great Lakes region, and with the Treaty of 1818, which fixed the US-Canada border at the 49th parallel and allowed for the joint American and British occupation of the Oregon Territory. Monroe and Adams were also able to achieve a longstanding American goal of purchasing Florida from Spain. This came on the heels of the First Seminole War, in which US soldiers under General Andrew Jackson invaded Spanish Florida in 1818 to fight against the Seminole Native Americans in retaliation for their harboring of runaway slaves. In the course of the war, Jackson exceeded his authority by capturing the local capital of Pensacola and establishing US control over the local area. Rather than order Jackson to relinquish control, the Monroe administration decided to enter into negotiations to buy Florida from Spain. This resulted in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, in which the US purchased Florida for $5 million.

The most pressing domestic concern of Monroe's first term was the question of whether Missouri should be admitted to the Union as a 'slave state'. The Missouri Territory had initially applied for statehood in 1817, and, in February 1819, the House of Representatives was considering legislation that would allow Missouri citizens to draw up a state constitution. Naturally, the question of slavery arose, with New York Congressman James Tallmadge, Jr., proposing an amendment to the legislation that would prohibit any more slaves arriving in Missouri and would free the children of the slaves already there once they reached the age of 25. The so-called Tallmadge Amendment passed in the House but was defeated in the Senate, bringing the question of Missouri's admittance into the Union to a standstill. This debate would ultimately lead to the Missouri Compromise of March 1820, in which Missouri was admitted to the Union as a 'slave state' in exchange for Maine being admitted as a 'free state'. Monroe, though personally opposed to any geographic restrictions on slavery, signed the compromise into law.

Second Term: 1821-1825

In 1820, Monroe won re-election without any major opposition. Indeed, he won all but one electoral vote, with the sole holdout, William Plumer, casting his vote for John Quincy Adams. While American folklore asserts that Plumer did this to protect George Washington's legacy as the only unanimously elected president, in reality, he simply did not think Monroe was a good candidate. Foreign policy in Monroe's second term was concerned with the Latin American revolutions, as his administration recognized the independence of the republics of Mexico, Chile, Peru, Argentina, and Columbia. Domestically, he had to deal with the fallout of the Panic of 1819, the first major economic depression to hit the US since the 1780s. Monroe believed that improving the nation's infrastructure would help the economy but refused to sign off on federal funding for such projects, believing that doing so would infringe on the autonomy of the states. Monroe also supported the relocation of free African Americans to the colony of Liberia in Africa; his support came less from altruism than from his fear of armed Black uprisings in the South. Nevertheless, the capital of Liberia was named Monrovia in his honor.

The most important accomplishment of Monroe's second term – and arguably of his entire presidency – was the 'Monroe Doctrine'. Written in close conjunction with Secretary of State Adams, the Monroe Doctrine was first articulated by the president in a message to Congress on 2 December 1823. Essentially, the doctrine warned European powers from interfering in the affairs of the Americas. The US would remain neutral in European affairs, but in return, Europe must not try to recolonize or re-establish influence in the Americas, which were now within the United States' sphere of influence. While the doctrine did not make much of an impact during Monroe's actual presidency, it would become a cornerstone of US foreign policy in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

Retirement & Death

Monroe finished out his second term, remaining largely aloof from the four-way presidential election of 1824, which was won by John Quincy Adams. After leaving Washington, Monroe retired to his farm of Oak Hill in northern Virginia. He had left the presidency significantly in debt and was forced to appeal to Congress for financial help, arguing that he had taken on the debt in service to the country. In 1826, Congress agreed to grant him $30,000 and would give him an additional $30,000 five years later. Monroe spent much of his retirement reading his books and would begin work on an autobiography that he would never finish. He did not entirely abandon public life, however, as he took part in a convention to amend Virginia's constitution in 1829.

After the death of his wife Elizabeth in September 1830, Monroe moved to New York City to live with his youngest daughter, Maria, and her family. His health steadily declined for the next half year, until he died on 4 July 1831 at the age of 73, making him the third US president to have died on Independence Day. Monroe is largely remembered as the last president of the 'Virginia Dynasty' (the others being Washington, Jefferson, and Madison) and for the stable, politically calm Era of Good Feelings. The question of the expansion of slavery, which had begun during Monroe's presidency, would intensify in the coming decades, while the 'Monroe Doctrine' would also be a major part of his legacy.