Jan Hus (also John Huss, l. c. 1369-1415) was a Czech philosopher, priest, and theologian who, inspired by the work of John Wycliffe (l. 1330-1384) challenged the policies and practices of the medieval Church and so launched the Bohemian Reformation. When he refused to recant his views, he was arrested and burned at the stake in 1415.

The Church at this time was the sole religious authority in Europe as well as a significant political power. One's eternal destination was dictated by how well one followed the Church's precepts, and since heaven, purgatory, and hell were understood as absolutes after death, people fell in line with church teachings to avoid an eternity of pain and suffering. The Church had strayed from its early spiritual concerns, however, and become more involved in world affairs by the time of the Middle Ages (c. 476-1500).

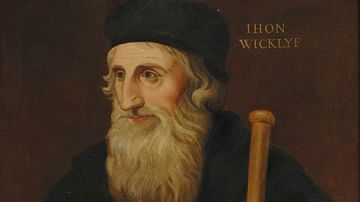

Dissent as early as the 7th century was condemned as heresy and silenced, but as one movement was crushed, another would take its place. John Wycliffe was an English priest and theologian who was fortunate to have the support of powerful nobles who were able to protect him, and although the Church eventually condemned him as a heretic and burned his works, many of them had already been copied and made their way to Bohemia.

Hus was a priest in Prague when he was introduced to Wycliffe's works and began his own challenge to the Church's policies, especially condemning the sale of indulgences, which the Church claimed would shorten one's time in purgatory or free the soul of a loved one. He was called before an ecclesiastical court under a promise of safe passage but then betrayed, imprisoned, and executed. His followers, known as Hussites, remained loyal to his vision, leading to the Hussite Wars of 1419 to c. 1434 between their forces and church loyalists who eventually won.

Still, the Hussites were not completely crushed and kept the so-called "Hussite Heresy" alive. Although Hus' views did not directly inspire the later efforts of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546), Luther would embrace Hus' teachings after he launched his own reform movement in Germany. Today, Hus is recognized, along with Wycliffe, as a proto-reformer; one who advocated for church reform prior to the Protestant Reformation of 1517-1648.

Early Years & Education

Jan Hus was born in Husinec, Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic) c. 1369, although some scholars have argued for 1372 or 1373. His family name is unknown as he was referred to as "Jan, son of Michaluv" (Jan, son of Michael), his father's first name. Nothing is known of his father, but it is thought he was most likely a peasant farmer or laborer as the family was from the lower class, and Hus later describes his early life as poverty-stricken. His mother taught him to read using the Bohemian Bible and also encouraged him and his brother to enter the priesthood as they would be able to live comfortably. Whether he had any other siblings is unclear.

Hus describes his early life as one of constant toil, living in a wattle and daub cottage with a leaky thatched roof and dirt floor on which the family slept along with their animals. He does not mention his father's occupation but relates how he helped his mother in plowing, planting, and harvesting crops. It is unclear whether farming was the family's primary occupation or if Hus' father worked elsewhere, but Hus' early years seem to revolve around agriculture, helping his mother, and learning the scriptures from the Bohemian Bible which had been translated from the Latin Vulgate to Czech by c. 1360.

At the age of nine or ten, Hus was sent to a nearby church (or, more likely, a monastery) to learn Latin. No reason is given for his leaving home, but most likely, it was at the insistence of his mother who hoped both her sons would become priests and escape the life of the medieval peasant. He was a capable student who impressed his teachers, and they recommended him for higher education in Prague, where he earned his Bachelor of Arts in 1393 and Master's in 1396.

Wycliffe & Hus

Hus was introduced to the works of John Wycliffe in 1402 by his friend Jerome of Prague (l. 1379-1416) who had been a student at Oxford University (where Wycliffe had taught) and copied some of his writings. Wycliffe had challenged the authority and biblical basis of the pope, criticized the luxury, ignorance, and greed of the clergy, argued against the validity of the sale of indulgences, and called for a return to the simplicity and poverty of early Christianity as described in the biblical Book of Acts.

The medieval Church, he claimed, had gone astray in the 8th century when it accepted the forgery known as The Donation of Constantine as valid. The Donation of Constantine was a document claiming that c. 315-317, Roman emperor Constantine the Great granted supreme power to the Church in temporal affairs after he was cured of leprosy by Pope Sylvester I. Pope Sylvester I, according to the story, then returned the gift, allowing Constantine to reign, but this was claimed by the Church to have set the precedent that it was only by the grace of the Church that a monarch, in any country, reigned and so the Church could involve itself in political and military matters. Wycliffe denounced The Donation of Constantine, the Church's land greed, and the obsession with temporal power both represented.

Hus not only agreed completely with Wycliffe but used the same words and arguments in his own challenge to the Church. Scholar David. S. Schaff comments:

Not only has he the main principles in common with Wycliffe, and also many of his quotations from the Fathers and the canon law and his proofs from Scripture [but] Huss appropriated paragraph after paragraph from his predecessor and transferred them often with little verbal change to his own pages. (xxvi)

Still, as Schaff notes, Hus did not simply plagiarize Wycliffe but used his arguments and examples as the foundation for his own. Whether Hus had already begun to question the authority of the Church before he was introduced to Wycliffe's works is unknown, but it is likely he had, and his own difficulties in reconciling church policy and doctrine with the scriptures led him to embrace Wycliffe's views. Hus was still a member of the Church in good standing in 1402 when he was appointed rector of the University of Prague and priest of the Bethlehem Chapel, but this was soon to change.

The Bethlehem Chapel was established in 1391 with the proviso that all observances would be conducted in Czech, not the Latin of the Catholic Church. The chapel could hold over 3,000 congregants, and Hus attracted an audience that would eventually overflow the building and carry his unorthodox teachings throughout the region. Using the Bohemian Bible, and preaching in the vernacular, Hus established a direct, personal relationship with his audience, and what he taught was at odds with the policies and practices of the Church.

Conflict with the Church

The Church at this time was divided by the Western Schism (1378-1417) during which there were two popes – Pope Urban VI in Rome and Antipope Clement VII in Avignon, France, who by 1408 had been succeeded by Gregory XII in Rome and Benedict XIII in Avignon. In his sermons, delivered twice on Sundays, Hus denounced the kind of politics that had created this situation and the corruption of the church hierarchy that allowed it. His criticism of the Church drew a significant crowd at both services and attracted the attention of Archbishop Zbyněk Zajíc (l. c. 1376-1411) who may have been sympathetic, but in any case, he did nothing to censure Hus.

King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia (r. in Bohemia 1378-1419, King of Germany 1376-1400), on the other hand, was definitely sympathetic as his consort Queen Sophia was a regular attendee at Hus' services and admired him. Concerned by Gregory XII's possible interference with his political goals, Wenceslaus IV decreed the clergy in Bohemia should remain neutral, supporting neither pope as legitimate. Hus and his Czech followers agreed to this while German clergy and others did not. Wenceslaus IV's 1409 Kutna Hora Decree then gave voting power at the university to the Czech clergy, resulting in the departure of the Germans and effectively giving Hus' Czech followers, and Hus himself, complete freedom to preach and teach whatever they wanted.

In an attempt to heal the schism, the clergy at Pisa elected a third pope, Alexander V, who was recognized as the true pope by Hus, his followers, and Wenceslaus IV. Alexander V, concerned with heresy in Bohemia, ordered Wycliffe's works burned (which was carried out by Archbishop Zajíc) but did not move against Hus. Alexander V died in 1410 and was succeeded by Pope John XXIII who sent out clergy to sell indulgences (in Bohemia and elsewhere) to raise money for his crusade against Naples. Hus vehemently opposed the sale of indulgences (as Wycliffe had) as unbiblical and avaricious.

Hus also advocated the practice of utraquism ("under both kinds"), in which both the bread and the wine were given to congregants during the celebration of the Eucharist at Mass, and criticized the present practice of priests offering the laity the bread but reserving the wine for themselves alone. Hus further condemned the pope for his crusade claiming that no Christian should advocate or encourage violence, least of all the head of the Church. Hus' sermons continued to be popular with the people who rejected the sale of indulgences and burned the papal edicts; in 1411, three of Hus' followers who defied the Church – Hudec, Kridelko, and Polak – were executed as heretics.

Rather than acknowledging the Church's verdict, Hussites took the corpses of the three men, already recognized as martyrs (as they are today), prepared them for Christian burial, and carried them through the streets from the town square to the Bethlehem Chapel. Hus himself performed the funeral service using the rites reserved for martyrs of the faith, rather than those for laity. He referred to the three as valuable treasures who had given their lives in the cause of truth and refuted the Church's claim of heresy.

Condemnation & Execution

The lines were now drawn quite clearly in Bohemia between followers of Hus (Hussites) and Catholics. Hus became the voice of the Czech people, separating Czech Christianity from the Catholic Church as a purer form of the religion. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch comments:

In his sermons, soon hugely popular in the city, Hus took up the theme of Church reform, and his enthusiastic backing by Czech noblemen [was significant]. Hus's movement became an assertion of Czech identity against German-speakers in the Bohemian Church and commonwealth, and it remained supported in all sections of society from the university to the village. (37)

As with Wycliffe in England, Bohemian nobles like Wenceslaus IV recognized that any power the Church lost meant more for themselves and so it was in their best interests to support Hus. Even so, there was no ignoring the Catholic Church or its adherents in Bohemia and so Wenceslaus IV attempted a reconciliation between the two factions in 1412. Both parties seem to have tried to compromise, but finally, their differences were simply too great. Hus refused to acknowledge the pope as head of the Church because the scripture made it clear that role belonged to Christ alone. Hus would later appeal directly to Jesus Christ, bypassing papal authority, in defending his teachings. He also refused to back down from his condemnation of the sale of indulgences and other policies that were not supported by scripture.

In 1413, Hus finished his famous work De Ecclesia (The Church) which drew upon Wycliffe to make Hus' definitive statement on the Church of his time and how far it had departed from the mission and vision of Jesus Christ. This same year, he also wrote a number of his other significant works including a criticism of the practice of simony – the placement of often incompetent and uneducated friends and family members of clergy to comfortable ecclesiastical positions – and pamphlets attacking specific clergymen. As with Wycliffe, these were printed using woodblock printing (xylography) and disseminated by his followers.

Wenceslaus IV's half-brother, Sigismund of Hungary (l. 1368-1437), who then held the title 'King of the Romans', involved himself in the dispute and convened the Council of Constance (also known as the Council of Konstanz, 1414-1418) to resolve the differences between Hussites and Catholics. Hus was given a promise of safe conduct to Konstanz by Sigismund, meaning he could not be imprisoned or otherwise harmed, so that he could explain his teachings. He arrived in Konstanz in early November 1414 and, while waiting for the conference to begin, preached to the people of the city. Catholic officials cited this as a violation of his safe-conduct pass and had him arrested.

Although Sigismund has been charged by some historians as complicit in Hus' arrest, it does not seem he was aware of it, and when the situation was brought to his attention, prior to Hus' execution, he was outraged that his word of honor had been so easily ignored. Hus' enemies, however, smoothed the situation over by noting that Hus was the source of both religious and civil unrest, had broken the agreement of safe passage by preaching at Konstanz, and the safe-conduct passage should be considered invalid. However Sigismund felt about the situation personally, he did nothing to intervene in the events that followed.

Even though he had been imprisoned and poorly treated by the Catholic officials, Hus still believed they would hear his cause and judge him fairly. He said he would be willing to recant if he could be shown from scripture – not church teachings – that he was in error. The officials ignored his gesture, demanded he recant, and when he would not, they turned him over to the secular authorities for execution. He was burned at the stake on 6 July 1415. His ashes were cast into the Rhine River afterwards to prevent his followers from housing them for veneration, and his works were condemned and ordered destroyed as heresies.

Conclusion

In the course of the later Protestant Reformation in Germany, a story circulated that Hus, at the stake, had predicted the coming of Martin Luther who would continue his work and vindicate his vision. This "prediction" is a later myth invented by Luther's followers after the Reformation was underway to associate him with Hus who, by then, was already understood by the Protestant faction as a proto-reformer and early martyr for the cause of religious freedom. Hus' friend, Jerome of Prague, would also be named a martyr as he was burned at the stake as a heretic a year after Hus' execution. Another of Hus' friends, Jacob of Mies (l. 1372-1429), avoided the same fate by carefully agreeing with the essentials of church doctrine while preaching the faith according to Hus.

It is unknown how Wenceslaus IV or Sigismund felt about Hus' execution as records of the time devote more space to the civil unrest that followed it. The Council of Constance had also condemned Wycliffe posthumously and ordered his works destroyed en masse, and this, along with the executions of Hus, Jerome, and others, sparked the Hussite revolt which led to the Hussite Wars in 1419. Scholar John Bossy comments on the Hussites and their initial unity of vision:

The outward face of their solidarity was an extreme hostility to Bohemian Germans and, after the burning of Hus, to the orthodox Church as a whole, which had brought upon the Czech nation a dishonor requiring to be avenged. (81)

The Hussites were initially victorious against the loyalist armies of the Church, thanks primarily to their general Jan Žižka (l. c. 1360-1424), a brilliant tactician, but were eventually defeated in 1434. Still, the Hussites had enough power to force the Church to negotiate at the Council of Basel in 1436, at which Bohemia was given the freedom Hus had fought for to observe its own version of Christianity.

In the present day, Jan Hus is recognized as a courageous proto-reformer who refused to compromise his vision and values and went to his death honorably for what he believed in. The Church officially apologized for Hus' execution in 1999, and he continues to be honored by members of many different Christian denominations, including Catholics, as a noble representative of the God he served.