Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441 CE) was a Netherlandish Renaissance painter who was famous in his own lifetime for his mastery of oil painting, colouring, naturalistic scenes, and eye for detail. Amongst his masterpieces are the 1432 CE Ghent Altarpiece, otherwise known as The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, and the Arnolfini Wedding Portrait, a tour de force in optical illusions. A pioneer of using oils for realistic effects, his work was influential on Renaissance art but especially on Italian artists in the second half of the 15th century CE.

Early Influences & Style

Jan van Eyck was likely born in Maaseik, Belgium c. 1390 CE. His family was aristocratic and he may have had an elder brother, Hubert van Eyck (d. 1426 CE), although this figure remains a highly mysterious one in the world of art (see below on the Ghent Altarpiece). Jan van Eyck was first active in art in 1422 CE when he worked for the Bishop of Liège. However, none of Jan's early works can be definitely attributed to him. Works are usually associated with his hand because of a belief (by no means certainly attested either) that he worked as an illuminator of manuscripts as a young man. It is for these stylistic reasons that Jan van Eyck (and/or his brother Hubert) are frequently identified as the creators of the miniatures within the illuminated manuscript known as the Turin-Milan Book of Hours.

Another early influence was the work of Robert Campin (c. 1378-1444 CE) who was active in Tournai, Belgium. The realism and luminosity in van Eyck's work may well have been inspired by Campin's paintings, even if van Eyck overshadowed him during the Renaissance period and beyond. Van Eyck's later works are more securely identifiable and are often signed or carry the inscription: 'Johannes de Eyck'. An additional mark of authorship was the artist's family motto: 'As best I can' or 'As I am able' (Als ik kan or Als Ich Can), perhaps also a pun on his own name. It is in his later works that we can best see his definite and quite unique style of painting.

In the 15th century CE tempera remained the most popular medium for paintings, but Jan van Eyck would master the technique of oil painting, one of the first Renaissance artists to do so, even if it was not a new medium. Oils allowed for greater subtlety in colours and tone, and they permitted the achievement of real depth in a painting that tempera panels or frescoed walls could not match. Consequently, van Eyck's work is typified by its high degree of naturalistic detail, achieved using the very finest of brushes. Everything in his paintings, from the skin of a face to the distant hills seen through a background window, is rendered in minute and utterly convincing detail. Other Eyckian features are the brilliant colours, rich texture and overall finish. Yet another feature of the artist's work is his frequent use of everyday objects in scenes to obliquely signify religious ideas. A shell, for example, signified the resurrection of Jesus Christ while Gothic architecture symbolised the New Covenant.

A Court Artist

From October 1424 to 1425 CE Jan van Eyck was employed as a miniaturist by John III, Duke of Bavaria and Count of Holland (l. 1374-1425 CE), a position which took him to The Hague. The artist then moved on to another court, this time that of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (r. 1419-1467 CE). Not only spending time in France, van Eyck was sent by his employer to Portugal in 1427 and again in 1428 CE, on both occasions to help secure a wife for the duke. It was in this capacity that he painted Philip's future wife, Isabella, daughter of the king, John I of Portugal (r. 1385-1433 CE).

Bruges & Portraiture

Jan van Eyck returned to Bruges around 1430 CE, although he continued to work intermittently for Philip the Good for the rest of his career. Settling in the city, he bought a house and married a girl called Margaret in 1431 CE. Bruges was a bustling trade centre, and the rich merchants there, who included many foreigners, were a good source of commissions for the artist. It was in this period that he produced many portraits, notably his Man with a Turban (1433 CE), now in the National Gallery of London, the The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (c. 1435 CE), today in the Louvre in Paris, and the sumptuously coloured Madonna with Canon van der Paele (1436 CE), now in Bruges' Groeningenmuseum.

The first of that trio is considered by some art experts to be a self-portrait. Created in 1433 CE, it shows van Eyck wearing an elaborate red chaperon, then fashionable headgear for the aspiring classes. The work is still in its original frame, interestingly, the only surviving original van Eyck frame that was gilded. Inscribed at the top of the frame is his motto in Greek letters while another at the bottom of the frame, this time in Latin, states "Jan van Eyck made me, 1433, 21 October". The artist also painted a portrait of his wife Margaret in 1439 CE, now in the Groeningenmuseum in Bruges.

The Chancellor Rolin is a portrait of Nicholas Rolin, then Chancellor of Burgundy, seated opposite the Madonna and infant Christ. Rolin is shown in prayer but the whole scene is symbolic of his wealth in this world with his sumptuous robes and fine palace. The painting shows van Eyck's mastery of light and colours, as well as his passion for detail, best seen in the window's columns and the river beyond which leads away to even more distant and hazy hills on the horizon. The abundance of churches in the town on the Madonna's side suggests this landscape was not meant to be a real one, or at least not of this earth.

An interesting double portrait is The Arnolfini Wedding, created in Bruges in 1434 CE. It shows the cloth merchant Giovanni Arnolfini with his wife Giovanna Cenami (although identification is not certain). Between and behind the two figures is a mirror in which we see their reflections, a trick by van Eyck to make the couple seem to be standing closer to the viewer. Even more ingenious is his depiction of two more people in the reflection, figures who must be standing where the viewer is, further confusing the lines between painted fiction and spatial reality. The artist has, significantly, boldly signed the work above this mirror. The painting is today on display in the National Gallery of London.

Van Eyck's portraits, like those of other Netherlandish painters, were striking in the direct relationship established between sitter and viewer, and in their high degree of realism, elements which would become standard in portraiture across Europe. Other much-imitated features of van Eyck's portraits are having his subject set against a plain dark background and having the subject standing or sitting at a slight angle to the viewer. Much more famous than all of these works, though, is the artist's greatest contribution to Western art, the altarpiece screen of Ghent cathedral.

The Ghent Altarpiece

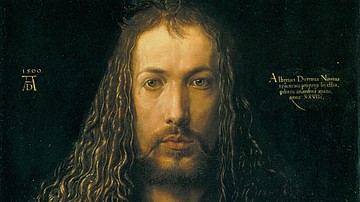

Jan van Eyck produced The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb altarpiece painting in 1432 CE. The work is more widely known simply as the Ghent Altarpiece. There is, however, a problem with certainly identifying van Eyck as the author of the piece. This is due to an inscription on it which states: "The painter Hubert van Eyck, greater than whom no one was found, began [this work]; and Jan, his brother, second in art [carried] through the task". It is dated 1432 CE. The authenticity of this inscription, which is actually a 16th-century CE transcription of the (possible) original, has been questioned by some art historians and linguists. Other historians have accepted the inscription and sought to identify which painted panels were done by which brother, although no consensus has been achieved there either. The major problem is that there are no other references anywhere else to Hubert's involvement in the piece and comments on it by such figures as Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528 CE), who saw the altarpiece in person in 1521 CE, make no mention of anyone except Jan van Eyck. Neither does the historian Marcus van Vaernewyck when he referred to the altar in 1562 CE. There was really, it seems, a Hubert van Eyck as he crops up three times in the municipal archives of Ghent. However, dating of the wood in the side panels reveals they cannot have been painted by Hubert who died in 1426 CE. As the art historian H. L. Kessler summarises, "whether this Hubert van Eyck was related to Jan and why in the 16th century he was credited with the major share of the Ghent Altarpiece are questions that remain unanswered".

The multiple-panelled, oil on oak altarpiece might encourage debate as to its authorship but one point on which art historians all agree is that it is one of the very greatest pieces of Renaissance art. Composed of 12 framed panels painted on both sides, it was originally meant to stand in what was then the Vijd Chapel of the church of Sanit John the Baptist, which has since become St. Bavo Cathedral. The work was commissioned by Jodocus Vijd, and he appears in the bottom left panel when the piece is closed shut; his wife, Elizabeth Borluut, appears in the lower right panel. The other panels on the reverse side show two prophets, two saints, two sibyls, the archangel Gabriel, and the Virgin Mary. It is the other side, though, which has the star panels.

When opened, the altarpiece measures 5.2 x 3.75 metres (17 ft x 12 ft 4 in). The lower central panel gives the piece its name and shows a crowd worshipping a lamb, symbol of Jesus Christ and his sacrifice at the crucifixion. Above is God flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist. The left wing of panels shows a naked Adam, singing angels and knights while the opposite wing has Eve, organ players, and hermit and pilgrim saints. The overarching theme is perhaps intended to be the redemption of humanity.

The figures in the often complex scenes are given a realistic three-dimensional appearance, but this is due to colouring and shading effects, they actually exist in a three-dimensional space which is illusional as mathematical perspective in art was then unknown in the Low Countries. The figures are given hyper-realistic details - see, for example, Adam in the far left panel and the praying patron of the piece with his anxious expression. The panels are all given jewel-like colouring and simulated gold leaf that would have made the scenes shine out from the dim recess of the church's altar.

The altarpiece has been threatened many times, from Calvinist extremists in the 16th century CE to German troops in the 20th century CE. Such was the high esteem in which the altarpiece was held, it was even mentioned in the 1919 CE Treaty of Versailles after the First World War. The treaty contained a clause that Germany had to return the altarpiece to the people of Belgium. It was returned but then stolen again during the Second World War. Fortunately, the altarpiece was rescued from its hiding place in an Austrian salt mine. In the 1940s CE, it was the first work of Renaissance art to undergo detailed scientific analysis. Today, it is back in the Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, but not in its original position.

Death & Legacy

Van Eyck died in 1441 CE and was buried in the Saint Donatian church in Bruges. Famous in his own lifetime, now his legend grew even further thanks to a plethora of admiring artists and biographers. Jan van Eyck's skill with oil paints, though, was so high he was extremely difficult to imitate, even if he was much admired across Europe. His work did influence such figures as the Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes (d. 1482 CE) and Gerard David (c. 1450 - c. 1523 CE). Van Eyck was also studied by such noted figures as Albrecht Dürer. Italian painters were keenly interested in van Eyck's techniques using oils, especially Piero della Francesca (c. 1420-1492 CE), Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510 CE) and (at least in some works on linen) Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506 CE). Indeed, by the end of the 15th century CE most major artists now used oil paints when working at an easel, not tempera. His work was appreciated by non-artists, too, and was collected, notable early aficionados being Alfonso the Magnanimous, King of Aragon and Naples (d. 1458 CE), the d'Este family in Ferrara, and the Medici of Florence.