War tales (gunki monogatari) is a genre of historical writing that developed in Japan from the Heian Period (794-1185) to the Muromachi Period (1333-1573). They form an important element in the development of the Japanese literary tradition, as they provide information about the various wars in Japan and became an important source of stories that were reused and popularized by subsequent generations of writers and dramatists.

Historicity

During the Nara Period (710-794) and the early to middle Heian Period, aristocrats at the imperial court dominated the government in Japan. Towards the end of the Heian Period, however, the power of the court began to decline, and large parts of the country came under the control of warrior clans. In the second half of the 12 century, a war broke out between two of these clans, the Taira and the Minamoto. The Minamoto clan was victorious, and in 1185, their leader, Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199), set up his own warrior government (called a bakufu in Japanese) which competed for power with the imperial court. This was based in Kamakura (near modern-day Tokyo) and was called the Kamakura Bakufu.

At the end of the Kamakura Period (1185-1333), Emperor Go-Daigo, who wanted to reassert imperial authority, enlisted the support of a rival warrior family called the Ashikaga and overthrew the Kamakura Bakufu. From 1333 until 1336, Go-Daigo ran his own government. This period is called the Kenmu Restoration. In 1336, however, the leader of the Ashikaga, Ashikaga Takauji, abandoned Go-Daigo and set up a new bakufu centered in the Muromachi district in Kyoto. Go-Daigo fled to Yoshino (in modern-day Nara Prefecture), and Takauji appointed a new emperor in Kyoto. For about 60 years, there was sporadic fighting between the rival 'Northern' and 'Southern' courts. In 1392, the Southern Court was tricked into submitting to the Northern Court, and the dispute came to an end.

The war tales are mostly concerned with describing these events. For many centuries they were thought to be accurate accounts written by contemporary, or near contemporary, observers. Modern historical scholarship, however, has revealed that this is not the case. They can best be described as 'literary histories' that combined some factual information with much fiction. This does not lessen their importance, but it means the content cannot be taken at face value. While it was once believed that the war tales reflected real warrior attitudes, it is now thought the fictionalized accounts of battles actually played a role in creating those attitudes amongst later generations of warriors. Popular ideas about bushido, 'the way of the warrior' or an 'unwritten warrior code' are also derived from these tales rather than from more factual accounts of warrior behavior.

The most important war tales are:

- Hogen Monogatari – an account of the Hogen Rebellion in 1156.

- Heiji Monogatari – an account of the Heiji Rebellion in 1159-60

- Heike Monogatari – an account of the Genpei War between the Taira and Minamoto clans in 1180-85

- Soga Monogatari – an account of the vendetta carried out by the Soga brothers in 1193

- Gikeiki – a work that focuses on the life of Minamoto no Yoshitsune, 1159-89

- Taiheiki – an account of the dispute between the Northern and Southern Courts in the 14th century

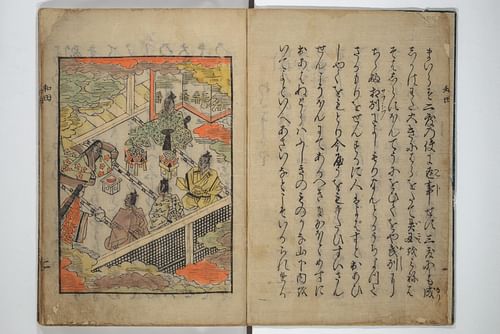

Some of these tales were written texts from the outset, while others were transmitted through an oral tradition and only written down later. This oral tradition consisted of the tales being recited by people called biwa hoshi. These were blind itinerant priests who accompanied their storytelling on a kind of lute called a biwa. The Heike Monogatari is an example of this kind of text.

The Heike Monogatari

The Heike Monogatari is known in English as the Tale of the Heike. It is the most famous of the war tales and is available in English translation. It is an account of the Genpei War between the Taira and the Minamoto clans. Confusingly, because of different readings of the Chinese characters in their names, the Taira are also known as the Heike, and the Minamoto are also known as the Genji.

The story is heavily influenced by the Buddhist ideas of karma and mujo, the impermanence of all things. The opening sentences are amongst the most famous in the Japanese literary tradition:

The sound of the bell of the Gion Temple tolls of the impermanence of all things, and the hue of the Sala tree’s blossoms reveals the truth that those who flourish must fade. The proud ones do not last forever, but are like the dream of a spring night. Even the mighty will perish, just like dust before the wind. (McCullough, The Tale of the Heike, 23)

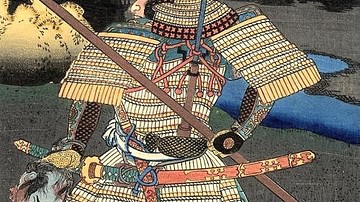

It is not known who the original author of the Heike Monogatari was and the tale exists in many different versions. The most commonly used one dates from 1371, about 200 years after the events described in the story. In its account of various battles, warriors demonstrate all the attributes that are now thought of as being the ideal samurai ones: personal loyalty, a willingness to sacrifice one's life for one's lord, and the determination to fight on to an honorable death rather than give in to a superior enemy. The problem is that, in other earlier versions of the tale, these accounts are either missing or different. The earliest versions of the story are much shorter and more factual. This suggests that the more heroic aspects of the story were fictional embellishments added later by biwa hoshi in order to make their performances more entertaining. For many centuries, however, people believed these additions were true.

The Taiheiki

The Taiheiki is an account of the war between the Northern and Southern courts in the 14th century. The name means something like "The Chronicle of the Great Peace", which is strange since it is mainly an account of war. It also exists in many different versions, but these are all rather similar because, unlike the Heike Monogatari, it was never recited and embellished by biwa hoshi.

It is divided into three sections:

- Books 1-12: from the accession of Emperor Go-Daigo in 1318 until the overthrow of the Kamakura Bakufu and the commencement of the Kenmu Restoration in 1333.

- Books 13-21: from 1333 until the death of Go-Daigo in 1339.

- Books 22-40: the war between the Northern and Southern courts and disputes within the Ashikaga Bakufu up until the death of the second shogun Yoshiakira in 1367.

Because of inconsistencies in the text, it seems different parts of the Taiheiki were written by different people. For example, the first section is very supportive of Go-Daigo, but the second section is very critical. The third section is the most incoherent part, with many repetitive descriptions of battles interspersed with supernatural accounts of ghosts and demons.

In its portrayal of warriors, the Taiheiki carries on some of the themes encountered in the Heike Monogatari, but it also elaborates on these. In the Heike Monogatari, loyalty is held up as a great virtue, but in the Taiheki loyalty to the imperial family is especially praised. Ashikaga Takauji is regarded as a great villain because he initially supported emperor Go-Daigo but then betrayed him. In contrast, the warrior Kusunoki Masahige is portrayed as a hero because he sacrificed his own life out of loyalty to the Southern Court, even though this turned out to be losing cause. In subsequent centuries, the failed loyalist hero became one of the most popular tropes in Japanese literature. Another prominent theme in the Taiheiki is warriors choosing to die by their own hands rather than being killed or captured by the enemy. In the Taiheiki, death is glorified, and this is sometimes taken to bizarre extremes as when, for example, two warriors kill themselves by cutting off each other's heads. Warriors committing seppuku is mentioned in earlier war tales, but in the Taiheiki, it becomes one of the main features of warrior behavior. There is, however, little evidence from other sources that this was actually common practice except when death at the hands of the enemy was almost certain.

Impact

The fictionalized accounts of Japanese warfare contained in the war tales came to have a powerful influence on the way subsequent generations understood warrior behavior. One of the best examples of this is a short story in section three of the Taiheiki concerning a provincial warrior called En'ya Hangan. One of shogun Ashikaga Takauji's deputies, Ko no Moronao, lusts after Hangan's wife, but when he is rebuffed, he tells Takauji that Hangan is planning a rebellion. Hangan tries to escape back to his home province with his family and retainers but is pursued by Takauji's men. Hangan's wife is killed, and he commits suicide. Before dying, Hangan prays that he will be reborn seven times so that he can become the enemy of Ko no Moronao again and again.

This is a relatively obscure story, and there is no evidence outside of the Taiheiki that it ever took place. In the 18th century, however, it became famous when it was used as part of the plot in a play called Chushingura. This has been translated into English as A Treasury of Loyal Retainers but is much more widely known as the Story of the Forty-Seven Samurai. In the play, after Hangan's death, some of his retainers hatch a plot to get revenge on Ko no Maronao. They wait several years until he is off his guard and then launch a night attack on his mansion. He is beheaded, and his severed head is carried to the temple where Hangan is buried, and it is presented as an offering. Having attained their goal, the play ends with the warriors preparing to commit seppuku.

This incident would probably have been completely forgotten were it not for the fact that it was taken up and used as the basis for Chushingura, the most famous play in the history of the Japanese theatre. Chushingura, which also contained elements from a contemporary scandal called the Ako Incident (1701-3), is a good example of the way episodes in the war tales were adapted as new art forms developed. It was first performed in 1748 as a bunraku play. Bunraku was a new form of theatre in the Edo period (1603-1867). In it, puppets that are about half the size of real people are each operated by three performers. The performers are in full view of the audience but dressed in black to indicate their invisibility. A narrator sits at the side of the stage and recites the story including the dialogue of all the characters.

The most famous writer of bunraku plays was a man called Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724). He drew heavily on stories from the war tales for his plays. For example, he wrote twelve based on the Soga Monogatari alone. In English, this is known as the Tale of the Soga Brothers. It describes an event that took place in 1193 CE in which the Soga brothers took revenge on a retainer of shogun Yoritomo no Minamoto (1147-1199) who they held responsible for the death of their father. This incident was of no significance politically, but for many centuries, it was regarded as the archetype of kataki-uchi, seeking revenge for the death of a blood relative. These kinds of revenge attacks do not seem to have been particularly common amongst real warriors, but they became a popular theme amongst dramatists in the Edo period.

As each new generation came along, stories from the war tales have been reworked and new elements added. This process continues today, as they are still regularly used in movies and television shows even though the war tales themselves make for dull reading.