The Jay Treaty, formally known as the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, was a controversial treaty signed by representatives of the United States and Great Britain in November 1794. It sought to resolve issues left over from the American Revolution (1765-1789) and establish trade between the two nations.

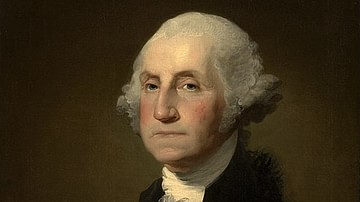

At the time of the treaty's signing, the United States appeared to be on the brink of war with Great Britain. Believing the United States to be reneging on agreements made in the Treaty of Paris, Britain refused to evacuate its troops from forts in the Northwest Territory and attacked American shipping in the French West Indies, seizing over 250 American merchant vessels and impressing their crews into service in the Royal Navy. Although many Americans clamored for war, President George Washington (served 1789-1797) believed the young republic was not strong enough to withstand another war with Britain. Instead, he dispatched John Jay, Chief Justice of the United States, to negotiate a treaty that would, hopefully, avert an armed conflict.

Jay succeeded in avoiding war, and even managed to strengthen commercial ties with Britain; the US was granted 'most favored nation' status at British ports, and American merchants were given limited trade rights in the British West Indies. However, the treaty came up short in many respects, as it significantly did not protect American sailors from future impressment. But the most controversial aspect was that the treaty created stronger political and economic ties between the United States and Britain, something that many Americans feared would lead to a re-emergence of aristocracy in the US. Riots broke out in many cities, and Jay was often burned in effigy. Even President Washington was abused in the press. A new political faction, the Democratic-Republican Party, emerged to combat the growing power of the pro-British Federalist Party. Revolutionary France, meanwhile, interpreted the Jay Treaty as an Anglo-American alliance and also began attacking American shipping, eventually resulting in the brief Quasi-War (1798-1800).

Background: The Threat of War

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 ended the American Revolutionary War, creating a state of fragile and uneasy peace between the fledgling United States and its former mother country, Great Britain. The treaty was generally regarded as favorable to the Americans: it more than doubled the size of the United States, whose borders now stretched as far west as the Mississippi River, and the British promised to evacuate their soldiers from these boundaries. In return for these concessions, Britain expected that all prewar debts owed by American borrowers to British lenders would still be paid and that state governments would stop confiscating the properties of Loyalists (Americans who had remained loyal to the British Crown during the Revolution). These were among the main components of the ten articles of the treaty, signed by American and British commissioners on 3 September 1783.

The ink on the treaty was barely dry, however, when troubles began to sprout. For much of its short existence, the United States had been plagued with economic difficulties; indeed, its recent attempt at a national currency, the Continental Currency, had failed after depreciating to the point of near worthlessness. State governments were imposing high taxes to begin paying off their own hefty war debts while Congress – under the terms of the Articles of Confederation – could not raise any taxes at all. Burdened by high taxes and inflation, many American debtors were unable to pay back their British creditors in a timely fashion. Additionally, many state governments were loath to take any pity on Loyalists, who were regarded as traitors; few were compensated for the properties that had been confiscated during the Revolution, with some states even continuing to seize Loyalist estates. Britain pointed to these two examples as evidence that the United States was not holding up its end of the bargain. In retaliation, the British maintained garrisons of troops in a series of forts in the Great Lakes region, which had been ceded to the US in the treaty. When the US complained, Britain promised that it would indeed evacuate these troops as promised – but only once the Americans had paid off all their debts.

Tensions between the two nations continued to simmer for the next decade. Then, in February 1793, Britain declared war on Revolutionary France. By this point, the French Revolution was in full swing; a French Republic had been proclaimed, King Louis XVI of France had lost his head, and hundreds of thousands of French citizen-soldiers were pouring into Europe to deliver liberty, equality, and fraternity at the points of their bayonets. Many Americans were quick to express their support for Revolutionary France, donning tricolor cockades, singing revolutionary songs, and opening political clubs called Democratic-Republican societies, in which they toasted the French Republic and denounced aristocracy. President George Washington, however, was more hesitant to offer support to the revolutionaries; such an act would certainly bring the US into conflict with Britain, a conflict that Washington knew they were not ready for. Instead, he issued a Proclamation of Neutrality on 22 April 1793, in which he promised to keep the United States out of the French Revolutionary Wars.

It did not take long for Britain to disregard this neutrality. Without offering so much as a warning, British ships began seizing American merchant vessels in the French West Indies, considering any ship carrying French cargo to be a valid prize. Over the course of the next year, around 250 American ships were captured and their crews were impressed into service with the Royal Navy.

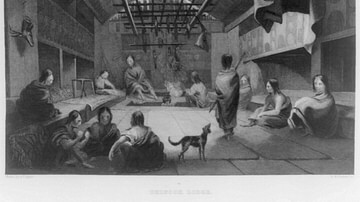

At the same time, the British used their forts in the Great Lakes region to offer support to the Northwest Confederacy, a loose coalition of Native American nations currently at war with the United States. These were blatant acts of aggression that could not be ignored; many Americans, particularly those associated with the Democratic-Republican societies, began to demand war. Other Americans were not so hasty. The Federalist Party, a nationalist political faction led by Alexander Hamilton, was horrified by the chaos and bloodshed of the French Revolution and did not want the US to fall under the influence of Revolutionary France. On the contrary, the Federalists viewed Britain as the natural ally of the United States; they believed stronger ties with the former mother country were vital for the survival of the US. Influenced by these Federalists, and still desirous to avoid war, President Washington agreed to send an envoy to London to hopefully reach an agreement and pull the quarreling countries away from the brink.

The Treaty

The man that Washington picked for the job was John Jay, the chief justice of the US Supreme Court. Jay was certainly a strong candidate for the job. He had decades of diplomatic experience, having helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris, and having served as US Foreign Minister during the 1780s. Now, he was told to not only avoid a war with Britain but also establish stronger commercial ties; specific instructions were provided to him by Hamilton, in which his various objectives were outlined. These included getting Britain to evacuate the forts on US territory, stop the seizure of American ships and the maltreatment of American sailors, and reopen the British West Indies to American commerce. Various Southern interests also wanted Jay to obtain financial recompense for the slaves that had been evacuated by the British at the end of the Revolution. It was a tall order, especially because Jay had almost no leverage with which to negotiate.

He arrived in London at the end of autumn 1794 and met with his counterpart, British Foreign Secretary William Wyndham Grenville. The two men spent some time hammering out the details of the treaty before finally putting pen to paper on 19 November 1794. Jay must have breathed a sigh of relief once the treaty was signed, as he had accomplished his main task of avoiding war with Britain. He had won some other victories as well; Britain once again agreed to abandon the forts in the Great Lakes region and granted the United States 'most favored nation' status at British ports. Britain even agreed to open the British West Indies to American trade, although this was limited to merchant vessels of 70 tons or less. All other outstanding issues – including compensation for American merchants whose ships had been seized and the issue of prewar debts – were handed off to joint arbitration commissions. Jay, an ardent abolitionist, had neglected to press the matter of compensation for the slaveholders. More significantly, however, he had failed to negotiate a provision that would prevent future seizures of US ships or impressment of US sailors. This issue would come back to haunt the US and would be a leading cause of the War of 1812.

Ratification & Controversy

Rather than risk the winter storms of the North Atlantic, Jay opted to remain in London for several more months, but he sent a copy of the treaty ahead of him. The copy landed on the president's desk in March 1795; immediately upon reading it, Washington knew it would prove deeply divisive, and he ensured that its contents remained confidential until the Senate could vote on it. On 8 June 1795, a special meeting of the Senate was held to look over the treaty. Many senators balked at the provisions, which came dangerously close to placing the United States back within Britain's sphere of influence; even as ardent a Federalist as Hamilton apparently referred to the treaty as "execrable" and "an old woman's treaty" in private (Chernow, 484). But, however undesirable the details, the Jay Treaty accomplished the Federalists' goals of strengthening political and economic ties with Britain. The treaty also virtually guaranteed that the Americans could trade anywhere in the world under the protection of the powerful British Navy.

Fierce debate in the Senate raged for two weeks before the Jay Treaty was finally ratified on 24 June. While its contents still remained a secret from the public, they would not remain so for long; a disgruntled senator soon leaked the treaty to a Philadelphia newspaper, which printed the full text on 1 July. The effect, in the words of James Madison, was like "an electric velocity" that spread to "every part of the Union" (ibid). Many Americans believed that republicanism would soon be undermined by a renewed British influence and accused Hamilton, Jay, and other Federalists of being traitors who were sacrificing American liberties for a pro-British aristocracy. Riots erupted in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, and in Charleston, protestors publicly burned a Union Jack. In Manhattan, Hamilton was pelted with rocks when he attempted to give a speech in defense of the treaty, while other rioters surrounded Washington's residence in Philadelphia, demanding he declare war on England. The Federalists' opponents became even more vocal about their pro-French sentiment, leading to the emergence of a new political faction. The Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, arose to resist the aristocratic policies of the Federalists and preserve republicanism in the United States.

Initially, most of the protestors' hatred was directed at Jay. "Damn John Jay," went the common refrain, "damn everyone who won't damn John Jay. Damn everyone that won't put up lights in the windows and sit up all night damning John Jay" (ibid). Throughout that summer, Jay was burned in effigy all across the country; indeed, Jay once quipped that he could walk the entire road between Boston and Philadelphia on a moonless night, guided only by the light emanating from his own burning effigies. But when President Washington signed the treaty in August 1795, some of the public's vitriol became directed toward him as well. The president was derided as everything from a monarchist to a military incompetent to a "usurper with dark intentions" (Wood, 198). Cartoons appeared in Democratic-Republican papers depicting Washington being sent to the guillotine, while some protestors called for him to be impeached.

Washington was certainly surprised and upset by the turn of public opinion, but an even worse betrayal was still to come. The House of Representatives still had to vote to appropriate the funds needed to fulfill the treaty, leading to a bitter two-month debate that had the potential to kill the treaty in its crib. The Democratic-Republican faction was led by James Madison, who demanded that Washington turn over the documents related to the treaty. The president refused and instead told the House that it had no authority over treaty-making and that such powers rested only in the hands of the president and the Senate. Finally, on 29 April 1796, the House of Representatives agreed to fund the treaty after a 48-48 deadlock was broken by the former House Speaker's tie-breaking vote. Washington was deeply hurt by the way he had been treated by Madison, once a trusted aid and friend; he never spoke to Madison again.

Consequences

The Jay Treaty had many consequences, some immediate and some long-lasting. The controversy over the document did much to increase the bitter factionalism that had already started to take root in the United States. It firmly pitted the nationalist, pro-British Federalist Party against the anti-aristocratic, pro-French Democratic-Republican Party, helping to shape the so-called 'First Party System' in US political history. Furthermore, the controversy had taken its toll on Washington himself, who was always acutely concerned with his own reputation. The backlash to the treaty, combined with concern over his age and health issues, led Washington to decide not to run for a third term, one of the most pivotal decisions ever made by a US president.

Like the Democratic-Republicans, the French were incensed by the Jay Treaty, which they interpreted as a British-American alliance. In late 1796, French privateers began attacking American shipping, seizing any American merchant vessels suspected of carrying British cargo; as had been the case two years earlier, nearly 300 American ships were captured and American sailors were mistreated. The new president, John Adams, hoped to emulate the success of the Jay Treaty by sending diplomats to Paris to negotiate a treaty. But when these diplomats arrived in Paris in October 1797, they were expected to pay a huge bribe before they were even allowed to meet with the French diplomats (a dispute later known as the XYZ Affair). Outraged, the diplomats returned to the US, and President Adams began building up the US Navy. This resulted in a brief, undeclared naval conflict between France and the United States called the Quasi-War, that ended in 1800, shortly after Napoleon Bonaparte came to power.

As for the Jay Treaty itself, benefits did quickly become apparent. Britain evacuated the northwestern forts in 1795, and the treaty led to ten years of lucrative trade between the two signatory nations, with the US becoming one of Britain's best customers; between 1794 and 1801, American exports to Britain tripled in value. Now protected by the Royal Navy, American merchant ships ventured into the Pacific Ocean, penetrating markets as far away as Indonesia and India. The value of American commodities rose rapidly, especially as the ongoing Napoleonic Wars in Europe created a demand for food. When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, he did not reject the Jay Treaty. However, neither did he renew it when it expired in 1805, a decision that helped lead to the resumption of hostilities between the United States and Britain, culminating in the War of 1812.