Jeanne d’Albret (Joan III of Navarre, l. 1528-1572) was Queen of Navarre, daughter of Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1549) and niece of King Francois I (Francis I of France, r. 1515-1547). She is best known for leading the Huguenots (French Protestants) in the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) and as mother of King Henry IV of France.

Her mother, Marguerite, and father, Henry d’Albret (Henry II of Navarre, l. 1503-1555), both favored religious reform, though neither left the Church, and Jeanne was brought up in a religiously liberal, intellectual atmosphere, tutored from a young age by the Humanist poet Nicholas de Bourbon the Elder (d. c. 1550). She was strong-willed at an early age and consistently followed her own course, openly declaring for the Reformation in 1560 and defying the demands of her second husband, Antoine de Bourbon (l. 1518-1562), that she return to Catholicism.

By supporting the Reformation and establishing Navarre as a haven for Huguenots, Jeanne increased the tensions that erupted in the French Wars of Religion. She initially supported the Protestant side financially and politically but, in the third war, took an active role as propagandist, figurehead, leader, and negotiated the peace twice in 1563 and 1570. She also, reluctantly, agreed to the marriage of her Protestant son Henry, (later King Henry IV of France, l. 1553-1610) to the Catholic Margaret of Valois (l. 1553-1615), daughter of King Henry II of France (r. 1547-1559) and Catherine de ’Medici (l.1519-1589) in the interests of national unity.

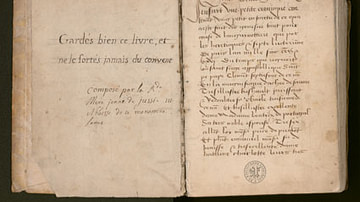

Like her literary mother, Jeanne composed poems, memoirs, and letters but was far more outspoken in favor of radical reform in her kingdom than Marguerite de Navarre. She died of natural causes in Paris in 1572, probably of tuberculosis, and was honored for her literary works and leadership, even by her adversaries. She is recognized as a major figure of the Reformation movement in France and one of the most significant political leaders of her time.

Education & First Marriage

Jeanne was born 16 November 1528 at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France. Her birthdate is sometimes mistakenly given as 7 January 1529 because that was the date her uncle, Francois I, announced her birth by granting permission for new guild masters in the cities. Jeanne was raised primarily by a governess, Aymee de Lafayette, her mother’s friend, and rarely saw her parents but Marguerite supervised her daughter’s education, visiting when she could, and made sure she had the best of everything. Scholar Kirsi Stjerna writes:

Jeanne had her own tutor, Nicolas de Bourbon, attendees for all her needs – including a pastry maker – exotic pets, and first-class entertainment. [She] enjoyed quality education with other private tutors, many of them representatives of the Reformed faith, especially during her early years when studying under her educated mother’s supervision. Exactly what she studied is less known, but for a young lady in her position, studies in Latin and in the literature of her own country and of the ancient world were to be expected. (159)

Marguerite de Navarre was highly educated, fluent in several languages, and a poet who was deeply religious and advanced the cause of the Reformation as it aligned with her Humanist philosophies. She remained a member of the Catholic Church but sponsored reformist writers, preachers, and theologians, frequently protecting them from persecution through the influence she had over her brother, the king. Jeanne grew up in an atmosphere of philosophical, religious, and political activity in a home which, even when Marguerite was not in attendance, welcomed Reformation activists. She seems to have been present during various discussions and grew up quickly as a free-spirited and independent thinker.

In 1537, the king moved Jeanne to Plessis-les-Tours, closer to the court and began the process of arranging for her a politically advantageous match (for him) in marriage. Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire proposed a match which was rejected because of Francois I’s enmity toward him, and Francois settled on Duke Wilhelm of Cleves (l. 1516-1592) of Germany, brother of Anne of Cleves (l. 1515-1557), the fourth wife of Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547). This match would cement ties with both the territories of Duke Wilhelm and with England and the marriage was set for June 1541 when Jeanne would be twelve years old.

Her parents opposed the marriage but there was nothing they could do as the king had already decided on the match. Jeanne, however, refused to go along with the plans quietly and made her objections known in writing to the king which she then had witnessed by members of her household:

I, Jeanne de Navarre, persisting in the protestations I have already made, do hereby again affirm and protest, by these present, that the marriage which it is desired to contract between the duke of Cleves and myself is against my will; that I have never consented to it, nor will consent; and that all I may say and do hereafter, by which it may be attempted to prove that I have given my consent, will be forcibly extorted against my wish and desire, from my dread of the king, of the king my father, and of the queen my mother, who has threatened to have me whipped by my governess. (Stjerna, 160)

It is unclear whether Marguerite ever actually threatened Jeanne with whipping or, as Jeanne later claimed, beat her herself, but it is established Marguerite intervened to try to change her brother’s mind, but without success. The marriage proceeded as planned but Jeanne refused to walk down the aisle and had to be carried to the front of the church by the Constable of France, Anne de Montmorency (l. 1493-1567). According to some interpretations, this was because of her extravagantly ornamented and heavy wedding dress but, as accounts allude to the bride “squirming”, it seems more likely Jeanne was resisting the marriage up to the last moment.

Marguerite refused to have her daughter accompany Wilhelm back to his lands until she had gone through puberty and began a letter-writing campaign to her brother arguing for annulment while Jeanne wrote to Wilhelm – courteously at first – with news of her daily life and wishing him the best. Marguerite and Jeanne kept this up for two years, continually offering excuses for why Jeanne could not travel to her husband, by which time Wilhelm had signed a treaty with Charles V and the marriage was no longer in Francois I’s political interests; it was annulled by the pope in 1545 on the grounds it had been forced on Jeanne and never consummated.

Second Marriage & Reformation

Between 1541-1547, Jeanne lived at her mother’s court which regularly hosted various intellectuals, poets, artists, and reformed theologians, writers, and priests. She was already sympathetic to the Reformation due to her youth among the same sort of people and her mother’s steady advocacy but now, as a young woman, began to take a serious interest in the subject. She was encouraged in this by her mother and her mother’s friends, including the Reformer Marie Dentiere (l.c. 1495-1561) who sent her books.

Francois I died in 1547 and was succeeded by his son Henry II who engaged Jeanne to Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendome. Jeanne was pleased with the match and the couple were married in October 1548. Stjerna writes:

The Huguenots were happy about the union as Antoine was known as a friend of the Protestants…The couple were infatuated with one another, for the time being anyway. Jeanne and Antoine together presented a powerful combination: their heirs would have some of the most legitimate claims on the French throne. After the death of their first child in infancy, two of the five children Jeanne gave birth to survived: her son Henry (born December 14, 1553) and her daughter Catherine (February 7, 1559) became both important players in France’s religious history, the latter as a committed Protestant, the former as the future King Henry IV of France. (163)

Antoine was known as a “ladies’ man” and may have had numerous affairs but the one confirmed was with Louise de la Beraudiere (l. 1530-1611), a lady-in-waiting at the court of Catherine de Medici (with whom he had a son, Charles III de Bourbon, future Archbishop of Rouen). Antoine’s support for the Reformation was as undependable as his fidelity to his wife and he seems to have advocated for whichever faction served his interests at any given time.

In 1555, Jeanne’s father died, and she and Antoine became queen and king of Navarre. Marguerite and Henry had already established Navarre as a haven for Protestants and the new royal couple continued this policy in advocating religious tolerance while both were, outwardly at least, confirmed Catholics. Later that same year, however, the couple traveled to the royal court at Paris in the company of a reformed ex-monk and preacher, Pierre David, who took the opportunity of every stop along the way to preach the message of reform. This continued until they reached the court where David was threatened by the Catholic King Henry II, quickly recanted to save himself, and was abandoned by Jeanne and Antoine who then returned to Navarre.

Antoine participated in Protestant religious ceremonies in 1558 but was drawn back toward Catholicism by his mistress (almost certainly at the direction of Catherine de Medici) while Jeanne, encouraged by letters from Reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) embraced the Reformation fully, publicly declaring herself a Calvinist on Christmas Day 1560. She reversed her former policy on religious tolerance in Navarre, confiscated the monasteries and convents, ordered all priests and nuns from her kingdom, and banned Catholic rituals. She then had the New Testament translated into Basque and the Bearnese dialect and encouraged literacy programs so more people could read scripture for themselves. Catherine de Medici countered this shortly afterwards, in 1561, when, acting as regent for her son Charles IX, she appointed Antoine Lieutenant General of France, driving a wedge between the couple as he would be expected to support Catholicism.

Betrayal & War

Jeanne’s new policies in Navarre added to the tensions growing between Protestant and Catholic factions in France which had been increasing since 1534. In March 1562, the Massacre of Vassy, in which Catholics killed 50 Huguenots, started the conflict known as the French Wars of Religion. Later that same month, Jeanne and Antoine, with their son Henry, were again at the royal court in Paris when Antoine publicly declared for Catholicism and demanded Jeanne do the same in the interests of national security as he blamed the Huguenots for the eruption of violence.

She refused and quickly left Paris for her own territories (though forced to leave Henry behind with his father) possibly escorted and protected by her brother-in-law Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Conde (l. 1530-1569), who had publicly declared for Protestantism prior to 1560 and was already leading the forces which would take Orleans from the Catholics the following month. While she was en route, stopping at the ancestral home of the Bourbons in Vendome, she (and possibly Louis) allowed a Protestant mob to sack the Catholic churches and destroy icons, resulting in Antoine’s order for her arrest.

He sent troops to apprehend and return her to Paris where he wanted her confined in a convent, but she hurried on from Vendome and arrived in the safety of her own lands before she could be caught. Calvin, upon hearing of Antoine’s betrayal of the cause and of Jeanne, denounced him as an enemy of truth and encouraged Jeanne in a letter to remain committed to the Protestant vision. She supported the Huguenot forces financially and fortified Navarre against a possible invasion. Antoine was mortally wounded in battle at Rouen in October 1562 and Jeanne sought safe-conduct passage to nurse him but was too late and he was attended at the end by his mistress Louise.

The war continued through March 1563 until a truce was called, mediated by Catherine de Medici and contributed to by Jeanne, resulting in the Edict of Amboise which, though it paused the conflict, did nothing to address causes. Both sides remained armed and antagonistic between 1563-1567 during which time Jeanne returned to Paris and took Henry back to Navarre while Pope Pius IV decreed her excommunicated and wanted her kidnapped and brought before the Inquisition. The pope also threatened to have her lands confiscated by any Catholic monarch who would have them which provoked a harsh response from Catherine de Medici and King Phillip II of Spain, both concerned over papal interference in Navarre, which forced the pope to back down.

Leadership of the Third War

Armed conflict broke out again in 1567 during which Anne de Montmorency, among many others, died, and was ended by another truce in March 1568, but the peace was broken by May and a third war began. Jeanne took an active role in the conflict by organizing logistics, planning and inspecting fortifications, and securing financing from Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) who supported her cause. She traveled to the troops to inspire them, bringing Henry with her, and fortified the city of La Rochelle as a Huguenot stronghold and base of operations. Stjerna writes:

Whether she could be called the “minister of propaganda” while at La Rochelle, she definitely exercised the functions of a queen and wrote manifestos and letters for financial support of the Huguenot cause. In addition to lending her personal support and presence to the Protestant resistance, she was in charge of the finances, personally giving her wealth, including her jewels, to secure the foreign loans needed for assistance. (171)

In 1570, Jeanne was instrumental in negotiating the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye with Catherine de Medici, ending the war and, that same year, the two women met to discuss the marriage of their children, Henry and Margaret of Valois, one Protestant and the other Catholic, to encourage unity. Jeanne was not happy at the prospect but agreed and the marriage was set for the summer of 1572. In June of that year, Jeanne returned to her apartments in Paris after shopping and fell ill. She was bedridden for days before dying, probably of tuberculosis, around 9 June 1572.

Conclusion

She died two months before the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre which resulted in thousands of Protestants being killed by Catholics throughout France beginning in Paris. The peace was broken again, and the French Wars of Religion would continue until 1598 when Jeanne’s son, now Henry IV of France, who had continued to fight for the Protestant cause, agreed to convert to Catholicism in the interests of peace (allegedly saying, “Paris is worth a Mass”) after realizing that France would never support a Protestant monarch.

His concessions to the Catholic faction, however, resulted in the Edict of Nantes (1598) which provided Huguenots with substantial rights in France, though it would also contribute to Henry IV’s assassination in 1610 by a zealous Catholic who considered him a traitor to the true faith. The Edict of Nantes did not end religious tensions in France which would later enter the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) in 1635, one of the worst conflicts in European history in which religion again played a significant role.

Jeanne d’Albret never set out to advocate for a Protestant France, only for the right of people to be able to worship God as they saw fit although, in her early zeal of 1560, she denied that same right to the Catholics of Navarre. Her uncompromising advocacy for reform, however, explained and justified in her memoirs and letters, inspired others to take a stand for religious reform in France and she is remembered today as one of the leading figures of the movement and among the most important of the early years of the Protestant Reformation.