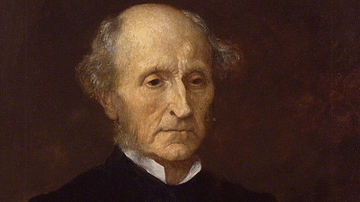

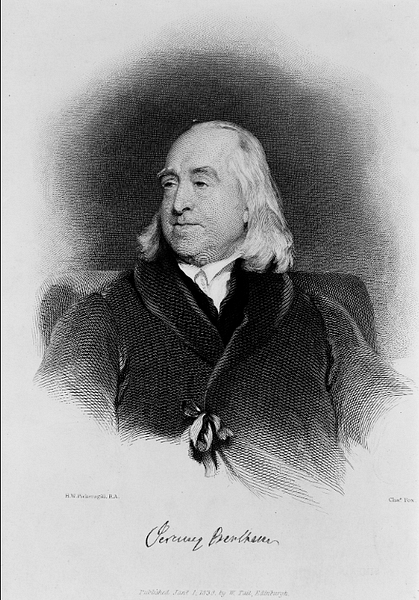

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was an English philosopher and liberal social reformer best known as the founder of utilitarianism based on the greatest happiness principle, that is, rationally judging the success of a law by considering how many people it makes happy. Bentham defined happiness as the presence of pleasure and absence of pain – criteria also applied to define moral behaviour.

Early Life

Jeremy Bentham was born in Spitalfields in London on 15 February 1748. Bentham's father and his grandfather had both practised law, and so, too, Jeremy studied that subject at the University of Oxford following a more basic education in the classics at Westminster School. Qualified by 1772, Bentham preferred philosophy to law, a pursuit he was able to consider thanks to his independent income. H. Popkin gives the following summary of Bentham's character:

Bentham was an extremely shy and sensitive person, who always felt insecure in the company of strangers…He wrote voluminously but published practically nothing of his own volition; friends would literally force him to publish material and when he refused, they would surreptitiously publish it for him. (37)

Bentham criticised some key concepts of the Enlightenment, notably the idea of natural rights and a social contract. He described such theories involving inalienable rights as "nonsense on stilts" (Blackburn, 417). For Bentham, only laws created rights. Bentham assessed these concepts and the traditional views on jurisprudence in his first major work, A Fragment on Government, published in 1776. The work was published anonymously because it was, in effect, a withering attack on Commentaries on the Laws of England by the highly-respected William Blackstone, published in 1765. Bentham was presenting a new alternative: laws not based on religious texts or tradition but a whole new, cohesive, and systematic law code based on achieving a happy citizen body.

Early Utilitarianism

Several thinkers had proposed a consideration of the happiness of the greatest number in their work, including Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), Claude-Adrien Helvétius (1715-1771), and Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794). It was Hutcheson who first coined the term "the greatest happiness of the greatest number" (Yolton, 236). Helvétius stressed that the only true motive of human action was the desire for pleasure and avoidance of pain; it is up to governments to manipulate these desires for the common good. Beccaria was focussed on increasing the general happiness of the citizen body by making sure crime was reduced through deterrents (although he was against unnecessarily harsh punishments and the death penalty). The work of John Locke was also important to utilitarianism as he provided the groundwork when he presented his idea that pleasure is equal to good and pain is equal to bad when considering matters of ethics.

Bentham's Greatest Happiness Principle

Bentham collected all of these earlier ideas together and presented his unique views on the greatest happiness principle in his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, published in 1789. Bentham believed that the goal of governments, laws, society, and individuals was to ensure the greatest happiness of the greatest number, this is, "the foundation of morals and legislation" (quoted in Law, 189). Bentham defined happiness as maximising the presence of pleasure and minimising the presence of pain. This philosophy became known as utilitarianism, and the method by which pleasure and pain were measured is known as the felicific calculus. The calculus, conceived as an objective measuring tool, measures happiness in units which are ranked according to several criteria, but in particular, the intensity, duration, proximity, and certainty of the pleasure or pain. Things which obviously appear in the pain category for utilitarians include hunger, poverty, abuse, injustice, torture, persecution, and disease. To rid society of these things, or at the very least minimise them, is obviously an excellent aim for any lawmaker, and having such clear criteria was a chief reason for utilitarianism's appeal. Another source of appeal is that the greatest happiness principle applies to all individuals equally.

As the historian H. Chisick points out, the happiness principle "is another instance of the aspiration, characteristic of the Enlightenment, to reduce politics to a science" (421). It also removed religion's influence from the field of ethics; Bentham, like most utilitarians, was an atheist. For Bentham, "Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do" (quoted in Law, 188). Bentham extended the happiness principle to animals because they also experience pleasure and pain. Consequently, he was also interested in animal welfare and one of the first thinkers to consider that animals also had rights, not just humans.

Bentham thought that other areas of life besides laws and governance would benefit from the happiness principle, and so he extended it to moral behaviour, judging that an action was right if it made more people happy than otherwise. This is often called act utilitarianism. The overall aims of utilitarianism, then, may be summarised as "the greatest good of the greatest number" in all senses.

This simple formula suited Bentham's liberal view that governments should minimise their interference in the lives of citizens. As long as citizens do not compromise the welfare of others, they should be permitted to pursue their own happiness as they see fit. Every individual, then, is being credited with possessing sufficient reason, self-restraint, and consideration for others to make the right choices according to the happiness principle. This is a very positive view of human nature. Ethical behaviour is made clear, individuals now know what to do and what not to do. As Chisick notes, "The limit of the individual's rights…stop in typically liberal fashion, at the point at which significant discomfort to others begins" (422).

Bentham saw a government's limited role as preventing infringements of happiness, and so he was primarily concerned with the rule of law, specifically as a watchdog to criminal laws. Bentham saw the role of governments as guiding citizen's natural instincts for happiness in such a way that the happiness of everyone (or as many people as possible) was achieved. Bentham believed that the fear of punishment deterred wrongful behaviour, but he only advocated the minimum punishment necessary.

Bentham's belief in a minimum of government interference also included the field of economics. He advocated laissez-faire economics. He believed anyone should be able to offer credit for investment, a view he presented in A Defence of Usury, published in 1787. One area where Bentham believed governments should seriously invest was education, seen by him as an essential way for the state to forge both intelligent and good citizens. Bentham's advice on what governments should and should not do was presented in his Manual of Political Economy, published in 1800.

Criticisms of Bentham

Utilitarianism has received several important criticisms. The first is that it is very difficult to define happiness (and even pleasure and pain). Not only is the concept rather vague but there is also the fact that the very same thing can bring some people happiness and others none, or certainly less happiness. This means that the felicific calculus is not at all objective but must be reduced to a matter of preference by the assessor. There is also the problem of conflicts of happiness between individuals and how to practically determine who is happy and who is not. There is the question of when will the happiness arrive, immediately or at some point in the future. If the latter, then how long in the future? If we must wait to see the full effects of an action, then this makes it very difficult to take a decision in the here and now. Even if all that were possible, some thinkers, notably Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), present a view that some people's happiness is more important than others, adding yet another layer of complexity to the not-so-simple felicific calculus.

Some critics point out that there are other considerations of the human condition besides utility and happiness/pain/pleasure. David Hume (1711-1776) was a philosopher who believed this. In some cases, a sense of justice or the right to life outweigh merely numerical considerations of how many happy or unhappy people an action will create. In addition, considering only individuals may conflict with the idea of a common good. Objectives like reducing disease and poverty are noble aims, but utilitarianism does not provide clear answers on how to achieve such objectives. Even for the individual, the principle of the greatest happiness really only tells one what not to do but rarely lays down any positive rules or values to follow. Neither does the system seem to allow for completely self-interested and unscrupulous individuals who do not care at all about the majority around them. Other philosophers have lamented utilitarianism's ethical focus on the consequences of actions rather than their motivations.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) thought happiness was not the concern of governments, but only the private concern of the individual, and so was not a proper consideration for politicians and lawmakers. Kant was one of those who firmly believed that we must consider the motivation of the person carrying out an act to determine if that act is morally good or not. Concentrating on consequences ignores the fact that good people can inadvertently do bad things and bad people can inadvertently do good things.

Further criticisms include the point that a law that is necessary and beneficial to society as a whole may bring unhappiness to at least some individuals. Even if successful, utilitarianism may well lead to a majority being happy, but what about the minority? Further, the minority may be a very large number of people indeed in any given society, strictly speaking, up to 49% of the population.

Some have criticised Bentham's presentation regarding his ideas. The historian H. Chisick states, "Bentham wrote a great deal, not much of it readable" (86). This is a little ironic since Bentham was an advocate of a new scientific language based on mathematical models in order to increase clarity when writing on complex and often ambiguous concepts and ideas. Still, the criticism can be equally applied to many other thinkers besides Bentham.

Bentham's Reforms

Bentham was very interested in improving society through reform. He founded the Westminster Review in 1823, which provided readers with an alternative voice in the conservative-dominated press of Britain at that time. More impressively, Bentham founded the University College London. Even more impressively, Bentham and his like-minded associates, known as 'the philosophical radicals', succeeded in that rare feat of actually affecting the contemporary political and social reality with their philosophy. Bentham and friends directly helped reform Britain's legal code. He did not succeed in his dream of making Britain a true democracy where women would have the right to vote, nor did his views on limiting British imperialism and curbing the excesses of the British East India Company affect policymakers. Nevertheless, Bentham's belief in the greatest happiness principle compelled him to push for reforms that reduced the obvious misery of many sections of contemporary British society.

Prisons and what to do with prisoners and how they should be treated were all hot topics in Britain in the last quarter of the 18th century since crime was rife. The number of prisoners in England and Wales had risen from 4,084 in 1770 to 7,482 in 1790 (Robertson, 460). Bentham thought a lot about prisons and designed what he called the Panopticon in his book of that title, published in 1791. This design allowed prison warders to observe prisoners at all times without themselves being observed. The Panopticon never became a practical reality since it was rejected by Parliament, although the idea of constant surveillance did become real enough in the 20th century thanks to developments in technology. Bentham thought that prisoners should be treated humanely and educated to reform their lives, although he also thought they should be made to work, too, and the profits go to the prison owner. He warned of the psychological damage that prolonged solitary confinement could bring upon a prisoner. Conversely, Bentham believed that only efficiency and no harm came from constant surveillance, an idea he would have extended to schools and factories. Bentham was against capital punishment in general and specifically against the death penalty then in place for same-sex relations; he called for an "all-comprehensive liberty for all modes of sexual gratification" (Robertson, 306).

Death & Legacy

Jeremy Bentham died in London on 6 June 1832. At his request, his body was first dissected and then embalmed; it is today kept at the college he founded where it sits, somewhat bizarrely, in a glass case for occasional exposure to exalted visitors.

Bentham's views on individualism and liberalism made him popular with radicals, particularly those involved in the French Revolution (1789-99). In 1792, the Convention Nationale awarded Bentham honorary citizenship. Utilitarianism, meanwhile, continued to gain admirers and was developed further by other philosophers, notably John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) and John Rawls (1921-2002). The principle of the happiness of the greatest number, despite its flaws, continues to influence governing policies worldwide, as noted by S. Blackburn: "As well as an ethical theory, utilitarianism is, in effect, the view of life presupposed in most modern political and economic planning, when it is supposed that happiness is measured in economic terms" (490).