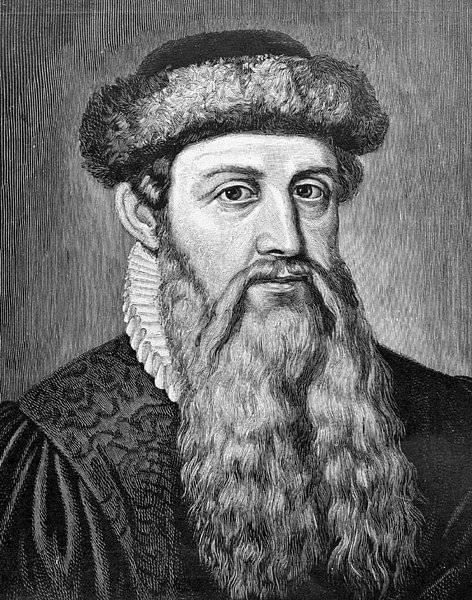

Johannes Gutenberg (l. c. 1398-1468) was the inventor of the printing press (c. 1450) who seems to have developed the device from wine and oil presses of the time. Gutenberg’s printing press not only revolutionized book making but literally changed the world in that ideas could now be shared over long distances with a wider audience than ever before.

The Gutenberg press also suggested the concept of machines taking the place of human labor in delivering uniform products to a mass market. Prior to Gutenberg, books were copied by hand or made using woodblock printing, which was time consuming, expensive, and resulted in a product few could afford. Afterwards, books could be produced quickly, cheaply, and uniformly. Every copy of a book was exactly like any other and, in a world where scribal error could often change meaning, this was a significant innovation.

Anyone who could write could now have their works printed and distributed and anyone who could read and had some disposable income could buy those works. Gutenberg understood the value of his invention and believed it would make him a wealthy man, especially after he printed the Bible in 1456, but his chief investor, Johann Fust (l. c. 1400-1466), called in his debt early, seized the press, and turned the operation of it over to his adopted son (and son-in-law) Peter Schoffer (l. c. 1425 to c. 1503). Fust and Schoffer then continued to print the Bible as well as other works and took credit for the invention of the press.

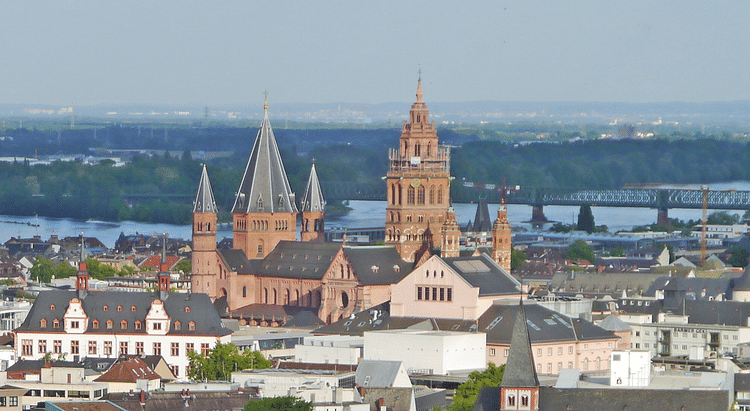

Although Gutenberg was recognized as the inventor of the press by the Archbishop Adolph von Nassau in 1465, and awarded a stipend, he died in relative poverty and was buried without fanfare in a church cemetery in Mainz. His invention is understood as one of the most significant contributions to world culture and understanding in history. The printing press in Europe enabled:

- An increase in the volume of books produced compared to handmade works

- An increase in the access to books in terms of availability and cost

- An increase in authors published, including unknown writers

- Successful authors earning a living solely through writing

- An increase in the use and standardization of the vernacular as opposed to Latin in printed works

- An increase in literacy rates

- The spread of ideas concerning religion, history, science, poetry, art, and daily life

- An increase in the accuracy of canonical texts

- Movements could now be more easily organized by leaders who had no physical contact with their followers

- The creation of public libraries

- The censorship of books by concerned authorities (Cartwright, 2020)

Gutenberg’s press facilitated and empowered the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, the Age of Enlightenment, and the Scientific Revolution by providing the means for mass consumption of ideas on a scale never imagined possible before.

Early Life & Education

Although the city of Mainz declared 1400 as Gutenberg’s official year of birth in 1900, the date is unknown and generally held to be between 1394-1404. He was the second of three children born to the aristocratic couple Friele Gensfleisch zur Laden and Else Wyrich. His father was “of the House of Gutenberg”, the name of his ancestors, and Johannes either took the name or shortened “Johannes Gensfleisch zu Gutenberg” to Johannes Gutenberg. Although the question of his name has been debated, it is unknown how or when he went by Gutenberg as almost nothing is known of his early life and very little about him overall.

His father was a wealthy goldsmith in Mainz and his mother came from nobility. Johannes is thought to have worked as an apprentice to his father in the mint. In 1411, when an uprising against the aristocrats of Mainz forced many into exile, Johannes’ family moved to one of his mother’s estates in Eltville am Rhein. In 1418 he is thought to have been enrolled at the University of Erfurt where he may have studied goldsmithing. A student by the name of Johannes de Altavilla is on record there for that year and Altavilla is the Latin form of Eltville am Rhein. By the time he was at Erfurt he would have already been literate in German and Latin, the two languages evident in his later work.

His father died in 1419 and he received an inheritance, but nothing is known of his life between 1419-1434 when a letter dated March 1434 places him in Strasbourg. Court records for the year 1436-1437 suggest he broke a marriage agreement to a woman named Ennelin but who she was is unknown as are any details of this event. In 1439 he is on record as investing in a business venture involving highly polished mirrors. Christian pilgrims visiting sites in large numbers could not always get close enough to the holy relic to derive its spiritual power and so it was thought that mirrors, held up above the crowd to reflect the relic, could catch some of its essence.

The city of Aachen was planning a grand exhibit of relics from Charlemagne’s collection and Gutenberg went in with some others to finance the production of a large number of mirrors they would sell to the crowd. A flood and plague canceled the exhibit, however, and Gutenberg and his associates were left with hundreds of mirrors no one wanted. There seems to be some suggestion that the mirror venture was Gutenberg’s idea because it is said he needed to placate the others by promising to share with them a secret project he had been working on that would make them all wealthy men. This secret project is thought to have been the printing press.

Books Before Gutenberg

Gutenberg was not the only person interested in creating a faster, better means of making books. Scholar Malcolm Vale notes:

A lay readership was in existence well before Johannes Gutenberg began to print with movable type. Manuscript production was a thriving industry, subject to guild regulations in most northern towns and many of the vernacular books from these workshops were paper copies, which were much cheaper to produce and to purchase than parchment. They met a demand for inexpensive, often unbound, books in English, French, Netherlandish, and German among a less affluent clientele. Taste tended to be dictated by what was available and by the preferences of the great nobles of the age. (Holmes, 346-347)

Books in medieval Europe were created from the parchment known as vellum, made of calfskin, while paper or papyrus – both known to writers of the Middle Ages – were condemned as “unchristian” by the medieval church as they had been used by pagan writers of the past and by “heathens” (Muslims) in the present. Vellum was time-consuming and expensive, however, and so by the 11th century paper, made by boiling cotton cloth and then drawing the fibers up on a screen to form a sheet, had become acceptable because it was cheaper and easier to produce.

Books were either copied by hand and illustrated – as in the case of the Illuminated Manuscripts – or printed using xylography (woodblock printing). Woodblock printing had arrived in Europe from China (at some point prior to 1300) where it had been in use since the 9th century. This method involved carving the desired image or text onto a wooden block which was then inked and pressed onto paper. A new block needed to be carved for each page of text and blocks would wear out through repeated use but, still, this method could produce a book faster than hand copying.

There was a demand for books among the nobility as well as the emerging literate middle class and so whoever could devise the means to produce high-quality books in large numbers could become quite wealthy. This is precisely what Gutenberg’s goal was and he unveiled it for his co-investors in 1440 in a book he called Adventur und Kunst ("Enterprise and Art"). It is thought that this book detailed his research and he had already built a working press using the skills he had acquired as a goldsmith and modeled on the wine and oil presses of the day, but this is unclear.

Mainz, the Press & Fust

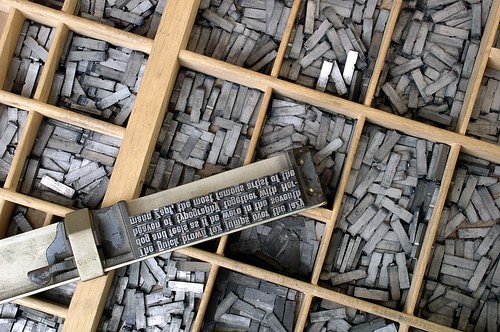

It is also unknown what he was doing between 1440-1448 but, by 1448, he had moved back to Mainz and taken a loan out from his brother-in-law Arnold Gelthus. It is assumed this loan was to finance the printing press, but this is unclear. By 1450, however, his press was in operation and the first work printed is thought to have been a poem, “The Sibyl’s Prophecy”, produced through Gutenberg’s invention of movable type.

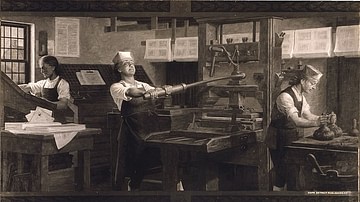

It is unknown what Gutenberg’s original method was of creating his type because so many presses proliferated so quickly afterwards. The plans and any description of the operation of his original press have never been found either and so any discussion of the first press is speculation based on those that were documented later. It seems, though, he drew on his knowledge of metal working to create a punch (a stick of metal) with a letter carved at one end. This was hammered into a copper bar creating a mold (a matrix). The matrix was then inserted into another mold which was filled with molten type-metal, and this produced a piece of type which, unlike a woodblock, could be used thousands of times before wearing out.

This process was repeated with all the letters of the alphabet as well as punctuation marks and the movable type was arranged in a rack. A wooden plate (the lower platen) was placed on the surface of the press and the type, face up, on the lower platen. The type was inked using two balls made of dog skin (because it had no pores) and stuffed with wool, held by wooden handles. After the inking, a sheet of damp paper was placed on the type (damp because it would hold the ink better and allow for a sharper impression) and then the upper platen was lowered onto the paper and pressed by the operator pulling on the press crank. Once one page was printed, it was removed to dry while the process began again.

Gutenberg’s press created uniform books which eliminated scribal error in copying, were easier to read than earlier books, and could also produce more books in a week than were previously possible in months or up to a year. Having proven the press worked, and knowing it would be profitable, Gutenberg secured a loan from a local businessman, Johann Fust, for 800 guilders (a significant sum equal to roughly three years’ annual wages for an unskilled worker at that time) to finance his new printing business which he set up in the building known as the Humbrechthof in the old part of Mainz.

Knowing the Church would be able to pay premium prices, one of the first items he printed were indulgences – writs sold to believers to shorten their time, or that of a loved one – in purgatory. Previously, indulgences were written out by hand, but the printing press meant they could be produced on a large scale with the space for the buyer and seller left blank. Indulgences could now be sold in far greater numbers which meant more money for the Church and, as they bought from him, more for Gutenberg. It is ironic that Gutenberg’s first financial success was in printing indulgences as these would be the catalyst for the Protestant Reformation when Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) objected to them in 1517. Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, condemning the wide-spread sale of indulgences, found an audience only because of the printing press.

The Bible, Fust & Schoffer

Gutenberg had hired Fust’s son-in-law (also referenced as his adopted son), Peter Schoffer, who had worked as a scribe and printer in Paris, as his master printer and Schoffer seems to have overseen the day-to-day operation of the press. Gutenberg, meanwhile, conceived of a much more ambitious project than printing indulgences. The Church needed Bibles for its cathedrals and other houses of worship and, before the press, copies required a lengthy process and were quite expensive. It is unknown how long Gutenberg worked to perfect the type for his Bible, but he published the first in 1456 (sometimes given as 1455).

He had at first wanted all the Bibles to be printed on vellum but that would have cost too much and so only a few used vellum parchment and the rest paper. After a Bible was printed, it was turned over to an illuminator who would decorate the cover and pages so it resembled an Illuminated Manuscript. People who could have never afforded an illuminated book in the past now found they could have one almost as nice at less than half the price. The Gutenberg Bible was printed with 42 evenly spaced lines per page, making it easy to read, and ornamented for aesthetic appeal, making it very popular.

Gutenberg had borrowed another 800 guilders from Fust at some point between 1450 and 1456 but it is unclear why. The press seems to have been doing well from 1450 onwards so it has been suggested that Gutenberg may have wanted to expand operations – and possibly did have two presses running which required additional staff – necessitating the second loan. Whatever his reasons for borrowing again from Fust, he no doubt regretted it when, in 1456, Fust charged him with misusing the money and demanded repayment. The loans had been given under the terms of a 6% interest rate and so Gutenberg owed Fust 2,026 guilders, a large sum he did not have. Fust sued him in court, won and, when Gutenberg explained he did not have the money, Fust was awarded his press and the business.

Exactly why Fust called in the debt, what the “misuse of funds” meant, or why Peter Schoffer testified against Gutenberg are all unknowns. It is possible, even likely, that Fust recognized how profitable the mass-produced Bible would be along with all the other works that could now be published through Gutenberg’s invention and decided to cut him out, replacing him with Schoffer and himself, who brought out a Book of Psalter shortly afterwards in which they took credit for the invention of the printing press.

Conclusion

Gutenberg may have then set up another print shop in Bamberg in 1459 after again borrowing money but is thought to have stopped printing in 1460, possibly due to failing eyesight, though this is unclear. In 1465, his achievement was recognized by Archbishop Adolph von Nassau who granted him the title of Hofmann – gentleman of the court – with an annual stipend, clothing allowance, and annual allotment of 576 gallons (2180 liters) of grain, and 528 gallons (2000 liters) of wine. Even so, Gutenberg died in relative poverty and obscurity three years later in 1468 and was buried in a Franciscan church’s cemetery in Mainz that no longer even exists.

His invention had, by that time, already spread across Europe, establishing printing centers which would grow to over 200 by 1520 and completely revolutionizing how people understood the world. Previously, most people’s view of the world was completely informed by their parents, neighbors, and parish priest. People lived and died in the same village or city where they had been born and had little knowledge of what life was like elsewhere or of people who thought or lived differently from themselves. Gutenberg’s invention changed all of that and, literally, changed the world. Scholar Aaron J. Keirns comments:

There are many individuals who deserve the honor of being named Man (or Woman) of the Millennium. Over the past 1,000 years every field of endeavor has produced exceptional men and women whose contributions changed the course of history. However, Gutenberg is somewhat unique. His work enabled the mass distribution of the printed word for the first time. Books changed everything. Like seeds scattered across the world, they sprouted new ideas and discoveries that have affected virtually every aspect of modern life. Even in our electronic age, the printed book is still a powerful force. (v)

After Gutenberg’s invention, tales of other lands, differing religious and philosophical views, political differences, were available to anyone with the money to buy a mass-produced book and those who could not afford that could hear books read aloud by those who could. The printing press opened up the world of ideas and the physical world in ways unimaginable before, allowing for the rebirth of knowledge in the Renaissance, the revision of religious belief in the Protestant Reformation, the development of other machines performing tasks once done by people, and the development of the science and technology that made the modern era possible.