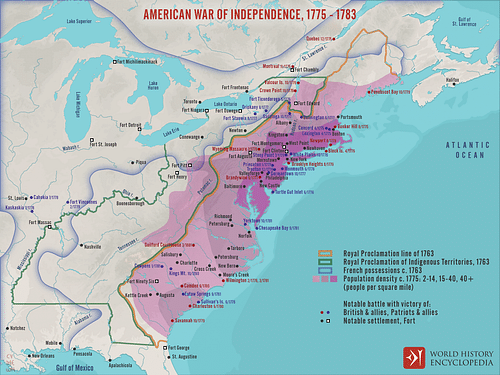

Major John André (1750-1780) was a British military officer who served in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). He is best known for negotiating with the American turncoat Benedict Arnold, who offered to hand over the stronghold of West Point. The plot was exposed when André was captured behind American lines, leading to his execution as a spy.

Early Life

John André was born on 2 May 1750 in London, England, to a family of wealthy Protestant immigrants. His father, Antoine André, was a prosperous merchant originally from Geneva, Switzerland, while his mother, Marie-Louise Girardot, was French. He was the eldest of five siblings; he had three sisters, Mary Hannah (b. 1752), Anne Marguerite (b. 1753), and Louisa Catherine (b. 1754), and a brother, William Louis (b. 1760). John was initially educated at Westminster School but was eventually sent to study mathematics and military drawing at the Academy of Geneva. He excelled at academics and showed proficiency in languages; by his late teens, he was fluent in English, French, German, and Italian. Yet his true passion rested in the arts. André would spend most of his free time sketching or painting, writing poetry and short plays, and playing the flute.

André returned to London in 1767 and longed to join the British army, which he saw as a chance to see the world and break free from the middle-class life to which he felt condemned. His father, however, had other plans, and put him to work in his countinghouse, hoping that John would one day inherit the family business. André dutifully worked for his father for two years until April 1769, when Antoine André died at the age of 52. Later that year, André accompanied his mother and sisters on vacation to Buxton Spa in Derbyshire, hoping that the trip would ease their grief.

It was on this trip that André became acquainted with Anna Seward, a noted poet who ran a literary salon out of her father's lodgings in Bishop's Palace in Lichfield. Seward invited André to Lichfield, where she introduced him to her childhood friend and poetic muse, the beautiful, yet reserved, 17-year-old Honora Sneyd. Seward doted on Sneyd and described her as "fresh and beautiful as the young day-star, when he bathes his fair beams in the dews of spring" (Seward, cxvii). André was quickly smitten with the girl and would often find excuses to be in her company. Although some scholars contend that Seward had romantic feelings for Sneyd herself, she appears to have aided André in his suit, reading love poems aloud as André and Sneyd dreamily held hands.

Before long, André proposed to Sneyd, but her father disapproved of the match, viewing André as too poor; he said that he would accept their engagement only if André gave up his military ambitions and instead devoted his time to making as much money as possible. Viewing a glimmer of hope, André raced back to London and plunged diligently back to work in the countinghouse. All the while, the lovesick André wrote letters to Honora, describing how much he hated life as a merchant but tolerated it because of his love for her:

When an impertinent consciousness whispers in my ear that I am not of the right stuff for a merchant, I draw my Honora's picture from my bosom, and the sight of that dear talisman so inspirits my industry that no toil appears oppressive. (Sargent, 15)

Within a few months, Sneyd's father grew impatient and became convinced that André would never make enough money. He abruptly broke off their engagement. Distance had perhaps cooled Sneyd's feelings for André, as she did not protest too strongly and was soon being courted by other men. Heartbroken, André decided there was nothing left for him in London. After working a little longer to provide money for his family, he purchased a commission in the British Army on 4 March 1771. He was selected for special training in Germany, where he spent two years before being assigned to the Royal Fusiliers (7th Regiment of Foot) as a second lieutenant. In 1774, André was sent across the Atlantic to join his regiment in Quebec, a deployment from which he would never return.

Arrival in America

On 2 September 1774, Lieutenant André stepped off the Royal Navy vessel onto the shores of America. His ship had docked in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a city that was currently hosting the First Continental Congress, and was therefore teeming with rebellion; André, in his resplendent scarlet uniform, could not have avoided the cold looks and harsh insults from the city's Patriots, many of whom viewed the British Army as the tool of their oppression. André could not get out of Philadelphia soon enough; sailing up the Hudson River, he landed in Albany, from whence he traveled alone and on foot through the semi-wilderness of upstate New York, hunting small game and sleeping beneath the stars. After arriving at Fort Ticonderoga, he boarded a schooner and sailed the rest of the way to Quebec. It was his first taste of America and the adventure he had been longing for.

André was still stationed in Canada in April 1775, when the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts began the American Revolutionary War. He and his regiment were sent to bolster the garrison of Fort Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River, shortly before the fort was besieged by an American army under General Richard Montgomery. The fort held out for nearly two months but finally surrendered in November when André and the rest of the garrison were taken as prisoners of war. Not impressed with his captors, André wrote to his mother that the Patriot soldiers were 'greasy, worsted-stocking knaves' (Randall, 378). He was sent to serve out his captivity in Lancaster, Pennsylvania; under the terms of his parole, he was granted freedom of the town and was allowed to stay at an inn at his own expense.

André spent about a year in Lancaster, splitting his time between hunting pheasant and grouse, and conversing with the local immigrant population in German. He also endeared himself to the family of Caleb Cope, whose home he was living in; André spent many hours giving art lessons to Cope's 13-year-old son and played with the other Cope children, who later recalled him "sporting with us children as if he were one of us" (Randall, 379). At the end of 1776, André was released in a prisoner exchange and rejoined the British army in New York City.

Fighting in Pennsylvania

André presented himself to the commander-in-chief of the British army, Sir William Howe, who was impressed with the young officer's talents; André's proficiency in German was essential for communication with the German auxiliary soldiers, or Hessians, serving in the British army, while his skill at drawing maps was also valuable. In January 1777, Howe promoted André to captain and recommended him as an aide-de-camp to Major General Charles Grey. André had rejoined the British army just in time for Howe's campaign against the United States capital of Philadelphia, which began in late August 1777, when the British army landed at Head of Elk, Maryland. André was present at the ensuing Battle of Brandywine (11 September), in which the Continental Army was outflanked and defeated; General George Washington managed to retreat with his army intact, depriving Howe of the decisive victory he needed.

For the next several days, the two armies tried to outmaneuver one another, with Washington sending Major General Anthony Wayne and 1,500 American soldiers behind British lines to harass their flanks. André wrote with irritation that Wayne was "watching our motions" and "infesting our rear on the march" (Randall, 380). Howe realized that Wayne must be dealt with and ordered General Grey to neutralize the threat. At 1 a.m. on 20 September, Grey's troops snuck up on the sleeping American camp near the town of Paoli. With André at his side, Grey ordered his men to remove the flints from their muskets and to attack only using the bayonet, to maintain the element of surprise. The British attack swept through the American camp as André himself would recall:

We ferreted out their pickets and advanced guards, surprised and put them to death, and, coming in upon the camp, rushed on them as they were collecting together, and pursued them with a prodigious slaughter.

(Daughan, 169-170)

The Battle of Paoli (or massacre, as the Americans called it) resulted in the deaths of 200 American troops; André and his fellow officers celebrated their victory by drinking the gin they found in the corpse-littered camp. The boldness of Grey's attack shocked Washington, who offered no resistance when the British army marched into the undefended Philadelphia on 26 September 1777. Washington gathered the resolve to assault a British garrison at the Battle of Germantown but was defeated; shortly thereafter, the two armies entered winter quarters, the Americans at Valley Forge and the British in Philadelphia.

Mischianza

During the nine months the British army spent in Philadelphia, the officers mingled with the city's Loyalist elite, attending lavish balls and dinner parties. The dark-haired, dark-eyed André, with his easy charisma and brooding romanticism, was popular among the ladies; he spent the winter courting Peggy Chew, the pretty daughter of Pennsylvania Loyalist Benjamin Chew. André took long walks with Peggy through her father's gardens, reciting poetry and playing the flute for her. He also struck up a close friendship with another Loyalist girl, 17-year-old Peggy Shippen, who made quite an impression on the British officers; André's friend, Captain Hammond, would later recall of Shippen that "we were all in love with her" (Randall, 392). By Christmastime, André was spending almost every evening at the Shippen residence, taking Peggy out for sleigh rides or to the theatre.

André took advantage of the downtime to showcase his love of the arts; together with his friend Oliver De Lancey, André converted a warehouse on South Street into a theatre. Although André himself was considered a 'poor actor' by local critics, he nevertheless put on 13 different plays over the winter, casting British officers and sometimes even prostitutes in acting roles. He would get another chance to show off his artistic abilities in the spring when it was announced that Howe was resigning his command and returning to England. André worked with De Lancey to put together a goodbye party for the general, which morphed into an ostentatious, 13-hour fête called the Mischianza (Italian for 'medley'). Held on 18 May 1778, the Mischianza was the largest festival of the American Revolution. It included a regatta of decorated barges along the Delaware River, a banquet, a firework display, and a mock tournament between 14 officers dressed as medieval knights, with shields designed by André.

During their occupation of Philadelphia, most British officers took up residence in the homes of prominent American Patriots who had fled the city. André lodged in the 3-story brick mansion of Benjamin Franklin on Market Street. He treated himself to the books in Franklin's expansive library and rummaged through his workshop, which contained many of the objects of Franklin's scientific experiments, such as the famous kite. On 18 June 1778, when it came time for the British to leave the city, André was spotted removing several valuable items from Franklin's home, which he claimed to be doing on General Grey's orders. Among these items was an oil portrait of Franklin by Benjamin Wilson; the portrait was returned to the U.S. in 1906 to commemorate Franklin's 200th birthday and now hangs in the White House.

Plotting with Arnold

After the British left Philadelphia, André accompanied Grey on his raids on several Massachusetts towns in September 1778. After Grey returned to England, André was promoted to major and selected as an aide-de-camp to Sir Henry Clinton, the new British commander-in-chief. Clinton was a solitary, standoffish, paranoid man who distrusted most other British officers, especially the former aides of General Howe. André nevertheless managed to charm and befriend the general, leading to his rapid promotion to adjutant-general in 1779. Clinton also put him in charge of British intelligence operations, in which capacity he began secret communications with American General Benedict Arnold.

Arnold was perceived as a war hero by the American public, having been wounded several times in service to his country. But after Congress had neglected to give him the promotions he felt he deserved, Arnold had become disillusioned with the American cause; embittered, close to financial ruin, and spurred on by his new bride, Peggy Shippen, Arnold offered his services to the British in exchange for money. For 16 months, Arnold and André communicated through encoded letters, often using Peggy as an intermediary, as Arnold supplied critical intelligence regarding American troop movements. In August 1780, Arnold was given command of West Point, a crucial stronghold that controlled access to the Hudson River. He offered to hand it over to the British army in exchange for £20,000. André accepted and arranged to meet Arnold in person to discuss the details of their plot.

On 21 September 1780, André traveled up the Hudson River aboard a Royal Navy sloop-of-war, HMS Vulture, which discreetly dropped him off on the river's west bank, near Stony Point, New York. He met Arnold at the home of Joshua Hett Smith (later referred to as the Treason House), conversing the entire night. At dawn, two American soldiers spotted the Vulture in the Hudson and fired at it with cannons, forcing it to sail downriver to avoid damage. When André returned to the shore to be picked up, he was shocked to find the sloop was gone; he was now stranded behind American lines.

Capture & Execution

André returned to the house to discuss his options with Arnold and the man who hosted the meeting, Joshua Hett Smith. The two men persuaded André to take the overland route back to British-occupied Manhattan; at Smith's suggestion, André removed his officers' uniform and dressed in civilian clothes to avoid detection. In his boot, he hid six papers written by Arnold that detailed how the British could capture West Point. Arnold also provided André with a fake passport to use in case he was challenged. On the evening of 22 September, André set out on horseback, escorted by Smith. The two men traveled north and crossed the Hudson at King's Ferry before making their way back south, toward British lines. They made it to Croton River, the southernmost point of American-controlled territory, where Smith turned back, leaving André to carry on alone; André ignored Smith's warning to keep inland, finding it easier to navigate by following the Hudson River.

He was half a mile north of Tarrytown when, at 9 a.m. on 23 September, he was approached by three militiamen. The leader, a man named John Paulding, wore a Hessian coat, leading André to believe the men were Loyalists; in fact, Paulding was a Patriot, who had used the coat to escape from a British prison only days earlier. André called out to the men, revealing that he was a British officer and asking that they escort him to the nearest British outpost. In response, the men replied that they were Americans. They pointed their weapons at André, ordered him off his horse, and searched him, finding the papers in his boot. André offered to give them his horse and watch if they let him go, but the men refused. They took him to the Continental Army headquarters at Tappan, New York, where he was kept prisoner. The captured papers exposed Arnold's treason, but the traitorous general escaped aboard a British vessel before he could be arrested.

Since he had been caught in civilian clothes and with a fake passport, André was treated as a spy rather than a prisoner of war. André protested that he had been acting as an emissary, not a spy; he had never intended to be left behind American lines, having been stranded there accidentally, and had only donned his disguise as a last resort, doing so with "great mortification" (Randall, 566). The Americans, however, were out for blood; someone had to pay for Arnold's treachery. On 29 September 1780, a board of senior Continental officers found him guilty of being behind American lines "under a feigned name and in a disguised habit" and sentenced him to death (Independence Hall). Upon hearing of André's capture, Clinton tried desperately to save his life, but Washington refused to release André unless Clinton agreed to give up Arnold, which he could not do.

His fate sealed, André wrote a letter to Washington asking to be executed by firing squad. Washington refused; having always executed spies by hanging, he feared that another method would undermine the assertion that André was, in fact, a spy. Washington disliked giving the order, however, and according to an eyewitness, his hand trembled as he signed the death warrant. On 2 October 1780, André was hanged in Tappan, at the age of 30. He stoically met his death, placing the noose around his own neck and tightening it, a spectacle that brought tears to the eyes of many in the crowd, including Marquis de Lafayette. After his execution, André was regarded as a war hero in Britain, and his death sparked a renewed wave of anti-American sentiment. His brother William was awarded a baronetcy in his honor. In 1821, Major André's remains were shipped to England and interred in Westminster Abbey.