John II Komnenos “the Handsome” was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 1118 CE to 1143 CE. John, almost constantly on campaign throughout his reign, would continue the military successes of his father Alexios I with significant victories in the Balkans, Armenia, and Asia Minor. The Byzantine Empire, thus, regained something of its former sparkle and the respect of its rivals across the Mediterranean.

Succession

John was born in 1087 CE, the son of emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE) and Irene Doukaina. When Alexios died of disease on 15 August 1118 CE, John, his chosen heir, became emperor as John II Komnenos. All very straightforward but things could have been very different. This is because it was actually Alexios' eldest daughter, Anna Komnene, who was for a time Alexios' official heir following her marriage to Constantine Doukas, the son of Michael VII (r. 1071-1078 CE). When John was born, he, naturally, became the chosen heir. However, when Constantine Doukas died an early death, Anna then married the gifted general Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger and plotted with her grandmother, Anna Dalassena, to make her new husband the next emperor. The plan failed largely because Nikephoros remained loyal to the official heir John.

Securing the Throne

John's nickname of "the handsome" and his general character is explained as follows by the historian J. J. Norwich:

Even his admirers admitted that he was physically ill-favoured, with hair and complexion so dark that he was known as 'the Moor'. He had, however, another nickname too: Kaloiannis, 'John the Beautiful'. This was not intended ironically; it referred not to his body, but to his soul. Levity he hated: luxury he frowned upon. Today most of us would find him an insufferable companion; in twelfth-century Byzantium he was loved. First of all he was no hypocrite. He was genuine, his integrity complete. Second, there was a gentle, merciful side to his nature that in his day was rare indeed. He was generous, too: no Emperor ever dispensed charity with a more lavish hand. (266-7)

One of the first acts of John's reign was, understandably, to banish his scheming sister Anna to a monastery, but at least this allowed her to write her celebrated Alexiad history of Byzantium in peace. John was indeed lenient with the other conspirators and their ring-leader Bryennios was even kept in service in the palace when, under most other emperors, he would have been blinded or executed. To ensure no future rivals conspired to oust him from his rightful position, John created an entourage of advisors and generals largely picked from outside the court. The supreme example of this policy was the selection of the emperor's childhood friend, a Turkish former slave called John Axoukh, for the position of megas domestikos or supreme commander of the army. One of Axoukh's many duties was to weed out any potential opposition to the emperor at court, especially as he was so often absent on his campaigns abroad.

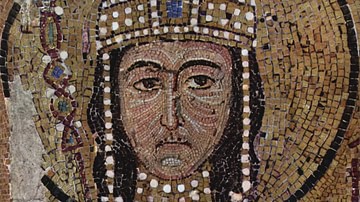

John married Irene, the daughter of King Ladislaus I of Hungary (r. 1077-1095 CE), and the pair is realistically depicted in a mosaic panel in the south gallery of the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. The mosaic dates to 1122 CE and shows the royal pair offering gifts to the Virgin and young Christ.

The State of the Empire

John inherited an empire in reasonable shape thanks to the stability of his father's long reign (by Byzantine standards) and Alexios' undoubted abilities as a general. The empire had resisted attacks from the Normans, and the 1108 CE Treaty of Devol promised no further hostilities between the two peoples. As a bonus, Alexios had gained a valuable ally in the Venetians in the process, although the price was reduced tax duties for the Italian merchants. The 1091 CE battle of Mount Lebounion had finally seen off the troublesome Pechenegs of the Eurasian steppe. Finally, the First Crusaders began to arrive in Constantinople from 1097 CE, and Alexios put them to good use by expanding the Byzantine military presence in Asia Minor and creating useful buffer fortresses against the ever-more ambitious Arabs. The Crusaders might have gone a little awry and captured such jewels as Antioch for themselves but at least they had been distracted from Constantinople.

Military Campaigns

John's military escapades continued where his father left off and the resurgent Pechenegs (Patzinaks) were once again defeated in the Balkans in 1122 CE. John had tricked the leaders by offering them gifts while his army attacked theirs. By no means a pushover, the battle was won thanks to the elite Varangian Guard, a mercenary corps of fearsome Vikings. Elsewhere, the Hungarians, now ruled by Stephen II, were pushed back into their own territory and the status quo restored, and, in 1129 CE, Serbia was obliged to accept Byzantine rule.

In 1126 CE the trade privileges of the Venetians were renewed, ensuring their continued naval support in Byzantine campaigns, but this was only after the emperor had removed the privileges and the Venetians had convincingly argued their case by attacking the coast of Asia Minor and several islands in the Aegean. In 1130 CE John campaigned in Asia Minor against the Danishmendids, the Emirs of Cappadocia. Following five expeditions there, John returned to Constantinople and celebrated a triumph in 1133 CE.

The successes kept coming and in 1137 CE the Rubenids in Armenia were conquered and their capital at Anazarbos occupied. Then, in 1138 CE, Antioch was attacked, the prized city having been in Crusader hands for the last 40 years. The current occupier, Raymond of Poitiers, was forced to swear loyalty and concede the city to Byzantine governance, although he actually went back on his promise to hand over the city. As the people of the city had revolted at the idea of returning to Byzantine authority, Raymond had actually had little choice in the matter.

In the west, as the Normans were expanding again in Italy and Sicily under the leader Roger II (r. 1130-54 CE), John made useful alliances in 1137 CE with the German emperor Lothar (r. 1125-37 CE) and then his successor Conrad III (r. 1138-52 CE). The alliance was strengthened in 1140 CE by the promise of marriage between John's younger son Manuel and Conrad's sister-in-law Sulzbach. Manuel had to wait five years and until he was emperor before the wedding finally took place. With the threat of Roger II diminished, John could look towards the east once more.

In 1138 CE John set off for a campaign against the Arabs in Syria, his army bolstered by a regiment of Knights Templar and a group led by Joscelin II of Courtenay, the Count of Edessa. The fortress city of Shaizar was selected as the first target and besieged. Before too much damage was done by John's siege engines, though, the Emir of Shaizar wisely offered submission and a large tribute. Once again, the emperor returned home triumphant.

In September 1142 CE John returned to the old chestnut of Antioch and marched into Asia Minor once again. Raymond, still basking in his title "Prince of Antioch", managed to stall for a time, and this necessitated the Byzantine army withdrawing for the winter. The city then gained an unexpected reprieve when the emperor died suddenly the following spring.

Death & Successors

John's reign ended in a freak accident while the emperor was out hunting; falling on a poisoned arrow or perhaps contracting septicemia from the wound. He died on 8 April 1143 CE. John was succeeded by his younger son Manuel, now Manuel I Komnenos, who would enjoy an even longer reign, lasting until 1180 CE. Manuel had been the chosen heir after the unusual decision by John to pass over his elder son Isaac and following the unfortunate deaths of two other brothers from fever. Manuel turned out to be even more ambitious than his predecessors but ultimately came unstuck with a failed invasion of Italy and then a defeat at the hands of the Seljuks. The loss of Venetian support following the withdrawal of trade privileges and the continued threat of the Crusaders all added up to troubled times indeed for the Byzantine empire going into the 13th century CE when the unthinkable happened and Constantinople itself was sacked.