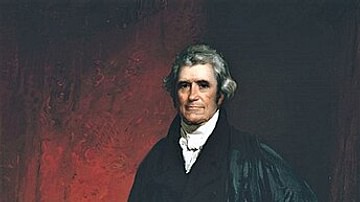

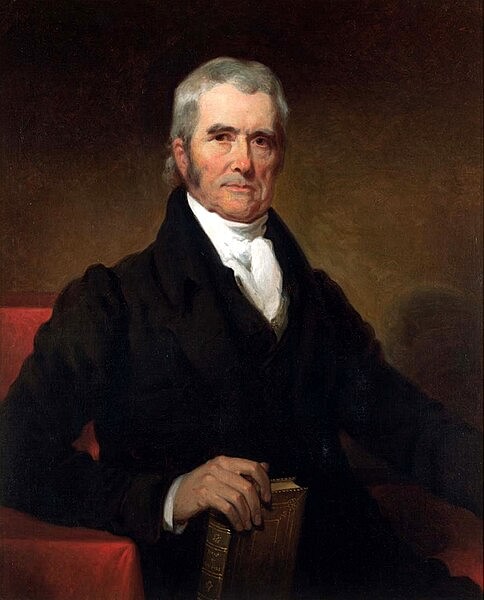

John Marshall (1755-1835) was an American lawyer and statesman, who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1801 until his death in 1835. Considered one of the most influential chief justices in US history, Marshall participated in over 1,000 decisions, including Marbury v. Madison, which established the principle of judicial review.

Early Life & Revolution

John Marshall was born on 24 September 1755 in a log cabin in the frontier community of Germantown, in Fauquier County, Virginia. He was the eldest of 15 children born to Thomas Marshall, a land surveyor who, over the course of his career, would accumulate some 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of land spread out across Virginia and Kentucky, making him one of the largest landowners along this frontier. Thomas Marshall, who had worked alongside a young George Washington to survey the land that would become Fauquier County, eventually became one of the county's most prominent citizens, serving as its first sheriff and later as its representative to the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg. In 1754, Thomas married Mary Randolph Keith, a reverend's daughter who was related to both of Virginia's leading families, the Randolphs and the Lees. She gave birth to John a year after her marriage; through her, John Marshall was a distant cousin of Thomas Jefferson, his future political rival.

Despite the pedigree of his mother's side of the family, John Marshall did not receive a gentleman's education. Instead, he was raised on the frontier, first in the wilderness of Fauquier County and later in the Blue Ridge Mountain region. He was easy-going, with simple tastes in clothing and food, and a manner that was rustic yet pleasant. His black eyes were said to have been full of intelligence and good humor, and his boisterous laugh was enough to put anyone at ease; one future colleague would later recall that Marshall's laugh was "too hearty for an intriguer" (Wood, 434). He was mostly home-schooled by his parents, although he did receive a few months of formal education at an academy where he befriended future president James Monroe. His education was cut short, however, by the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. His father had supported the Patriot cause and joined a militia regiment leaving John, dutiful to both father and homeland, to quickly follow suit.

In 1776, Marshall was incorporated into the Continental Army as a lieutenant. In the autumn of 1777, he served under General Washington in the Philadelphia Campaign, seeing action at the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown. When the army hunkered down for a bitter winter at Valley Forge, Marshall suffered through the cold and the hunger, shivering side by side with the other men; when the winter snows thawed into springtime mud, he drilled with them as well. In 1780, having risen to the rank of captain, Marshall was furloughed from the army and went off to the College of William & Mary to study law. As he left the military behind, Marshall reflected on his wartime experiences and came away with two beliefs that would greatly impact his career. The first was a fierce admiration for George Washington, whose integrity and determination led Marshall to believe that he was "the greatest man on earth" (Wood, 434). Second was a belief that the nation, were it to survive, needed a strong central government; Marshall's experience at Valley Forge, where Congress had struggled to keep the army supplied with adequate food and clothing, had been enough to convince him of that. Armed with these convictions, Marshall set out to embark on a legal career, one that would shape the destiny of the infant United States.

Political Career

At the College of William & Mary, Marshall studied law under the college's eminent chancellor George Wythe – who also mentored Jefferson – and was admitted to the Virginia bar later that year. In 1782, with the war as good as won, Marshall was elected to represent Fauquier County in the Virginia House of Delegates. He went to the state capital of Richmond where he worked tirelessly to establish a law practice in between legislature sessions. Somehow, Marshall found time in his busy schedule to court Mary 'Polly' Ambler, the daughter of the state treasurer, whom he married on 3 January 1783; the couple would ultimately have ten children, six of whom would survive to adulthood. After his marriage, Marshall continued to build up his law practice and was soon recognized as one of Richmond's most prominent attorneys.

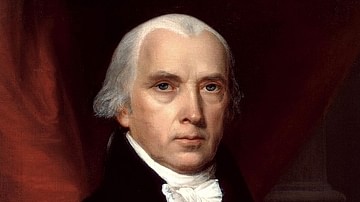

In 1788, he was elected to the Virginia Ratifying Convention, where he teamed up with James Madison to convince his fellow delegates to accept the new United States Constitution. The Constitution, which had been drafted in Philadelphia the year before, promised to strengthen the national government, leading Marshall to enthusiastically champion its ratification; he and Madison succeeded, though only barely, as Virginia ratified the Constitution by a margin of 89 to 79. In 1789, Marshall declined an offer from President Washington to serve as the US attorney for Virginia, preferring to focus on his law practice. Nevertheless, he was slowly drawn into local politics, forced to defend the Constitution and the strong national government he had helped create from its critics. In the early 1790s, as political parties began to take root, Marshall identified with the Federalist Party, which championed a strong federal government; indeed, Marshall worked with Alexander Hamilton to organize a Federalist movement in Virginia. Even as many of Marshall's fellow Virginians – including his onetime ally Madison – joined the rival Democratic-Republican Party, he remained steadfast in his commitment to Federalism.

Marshall managed to resist the allure of national politics until 1797, when he accepted an offer from President John Adams to serve on a three-man commission being sent to Paris, to hopefully deescalate tensions between the US and the French Republic. Upon arrival, Marshall and the other commissioners were appalled to learn that the French foreign minister would refuse to see them unless they first agreed to pay a substantial bribe. The commissioners refused to be cowed into submission and returned home; when Marshall arrived back in Philadelphia in June 1798, he found he had become a celebrity, toasted far and wide for his refusal to submit to French threats. After the XYZ Affair – as the incident with France became known – Marshall was persuaded to run for Congress by Washington, who feared that Federalist influence was floundering. Marshall won election to the House of Representatives and took his seat in December 1799, the same month that his idol Washington died.

In May 1800, President Adams appointed Marshall as his new secretary of state; the president had been impressed with Marshall's performance in the XYZ Affair and was moreover happy to see that Marshall did not put party above duty. Later that year, during the build-up to the turbulent US presidential election of 1800, Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth resigned, citing poor health. Adams offered the job to John Jay, a Federalist who had previously held the office during the Washington Administration. Jay declined, however, and by the time Adams learned of his refusal, he had already lost the election and was facing a Democratic-Republican takeover of the national government. This could have dire consequences for the courts, as many Democratic-Republicans despised the federal judiciary and wanted to do away with it.

Despairing, Adams asked Marshall where he could find a suitable Federalist candidate before his presidential term expired. When Marshall replied that he did not know, the president turned to him and said, "I believe, sir, I must nominate you" (McCullough, 560). So it was that on 31 January 1801, Adams signed Marshall's commission as chief justice of the Supreme Court, an appointment that the Senate quickly confirmed. It was a monumental decision that not even Adams could have had the chance to appreciate; Marshall would lead the Supreme Court for the next 34 years, during which time he would define its role in the United States government.

Chief Justice: Court Reforms & Marbury v. Madison

At the time Marshall took office – he was sworn in on 4 February 1801, a month before the end of Adams' administration – the Supreme Court was widely dismissed as an institution of little importance. In the 12 years between its inception and Marshall's appointment, it had decided only 63 cases, none of which had a lasting impact. The Court was not yet recognized as the interpreter of the Constitution, and the federal judiciary was generally distrusted as an aristocratic institution, a relic left over from monarchism. Marshall quickly set about remedying this situation. His first act was to increase the Court's legitimacy by having it speak with one voice. He ended the practice of seriatim, whereby each justice issued a separate opinion in a case; from now on, the Court would do its best to reach a consensus and issue a single majority opinion, which Marshall would often write himself. To eschew charges that the Court was aristocratic, Marshall did away with the Court's scarlet and ermine robes that resembled the ones worn by royal magistrates in England. Instead, he convinced his colleagues to wear the simple black robes of Virginia judges.

The Marshall Court would review its first major case, Marbury v. Madison, in February 1803. The case had its origins with the so-called 'midnight judges', the judicial appointments made by Adams in the last weeks of his presidency; along with Marshall's appointment to the Supreme Court, Adams had named 60 men to various federal courts, most of whom were Federalists. When Adams' successor, Thomas Jefferson, took office, he viewed this as a last-minute attempt to pack the courts with Federalists and instructed his secretary of state, Madison, to block the remaining appointments. One of these blocked appointees was Maryland Federalist William Marbury, who sued the State Department for his commission. Marbury argued that, by invoking Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Supreme Court could force Madison to give him his commission by a writ of mandamus. The case left the Supreme Court in a rather awkward situation. Should it side with Marbury and issue the writ of mandamus, the president could simply ignore the ruling, and the Court would be humiliated, its authority weakened. Should it side with Jefferson and Madison, the Court would appear to be nothing more than a presidential tool, and its legitimacy would likewise diminish.

Facing this lose-lose situation, Marshall arrived at a decision that is often regarded as one of the most brilliant in the Supreme Court's history. On 24 February 1803, he issued the Court's majority opinion, in which he stated that Marbury was indeed entitled to the office Adams had appointed him to and that the sitting president "cannot at his discretion spot away the vested rights of others" (Wood, 441). However, Marshall went on to say that the Court could not force Madison to deliver the commission by a writ of mandamus because the Constitution did not give the Supreme Court the authority to do so. Marshall claimed that the Court's power to issue a writ of mandamus, derived from Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, went outside the jurisdiction of the Court as outlined in Article III of the Constitution; therefore, Section 13 of the Judiciary Act was unconstitutional. Since the American people looked to the Constitution as "the fundamental and paramount law of the nation", Marshall concluded, then any "law repugnant to the Constitution…is void; and that courts, as well as other departments, are bound by that law" (ibid).

With this opinion, Marshall avoided making the Court look weak; he asserted Marbury was in the right but avoided provoking the wrath of the Jefferson administration by invoking a writ of mandamus. More importantly, however, the Marshall Court had just taken the unprecedented step of declaring an act of Congress to be unconstitutional and therefore invalid. The case established the Constitution as a legal, and not just a political, document and instituted the principle of judicial review, which meant that the courts could strike down any law that seemed to violate the Constitution.

The Marshall Court

During his three decades on the Supreme Court, Marshall would hear over 1,000 cases and would write the majority opinion for nearly half of them. Among these were other landmark cases that, like Marbury, strengthened the principle of judicial review. In the cases United States v. Peters (1809), Fletcher v. Peck (1810), and Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816), the Supreme Court established its right to review and reverse the decisions of state courts and laws of state legislatures. In 1819, the Marshall Court heard the case McCulloch v. Maryland, in which the state of Maryland had challenged the constitutionality of the creation of a national bank. In the case, the Marshall Court decided that Congress had the power to establish a national bank, asserting that there were 'implied powers' allotted to Congress in the Constitution. This case was another example of the Marshall Court deciding what powers the federal government had.

The Supreme Court met for only six or seven weeks every year, with each justice expected to conduct a circuit court in his off time. It was in this capacity that Marshall oversaw the treason trial of former vice president Aaron Burr in 1807, held in Richmond before his 5th Circuit Court. Burr had been arrested on suspicion of making some vague mischief in the West; some thought he was planning an invasion of Spanish-held Mexico, while others believed he had been preparing to carve out a new western country for himself. For political reasons, President Jefferson desperately wanted a conviction and worked diligently to secure one. However, Marshall was not convinced that Burr had done anything to warrant a conviction; under his working definition of 'treason', a perpetrator had to have actively taken up arms against the US government, something that Burr had not seemed to have done. As a result, Burr was acquitted, leading to mass protests where both Marshall and Burr were burned in effigy. After Burr went into self-imposed exile to Europe, however, the anger against Marshall died down.

From 1819 to 1822, the Marshall Court entered its so-called golden era, a time when it reached the peak of its influence. In 1819, the same year as the McCulloch decision, the Court heard Dartmouth College v. Woodward, in which it ruled that the college's charter could not be interfered with by a state legislature. Cohens v. Virginia (1821) established the Supreme Court's right to hear appeals from state courts on criminal lawsuits, and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) asserted the federal government's ability to regulate interstate commerce, even if it had to override state laws in the process. The personnel of the Court remained the same between 1811 and 1823, creating a strong bond between the justices. But after this golden age, Marshall slowly began to lose influence in his own court, as his friends died or resigned and were replaced with new justices. Especially after the inauguration of Andrew Jackson – a man whom Marshall had denounced as a demagogue – did the chief justice start to see his influence in Washington decline.

In 1831, the Supreme Court heard the case Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, in which Marshall ruled that the Cherokee and other Native American nations constituted "domestic dependent nations" over which his court had no jurisdiction. The next year, the Marshall Court decided in Worcester v. Georgia that the state's law that prohibited Native Americans from entering Georgia lands without a license was unconstitutional. These decisions earned Marshall the enmity of President Jackson, who accused the Chief Justice of violating states' rights. Jackson, therefore, refused to enforce the decision reached in Worcester. One of Marshall's final landmark cases was Barron v. Baltimore (1833), in which the Court ruled that the Bill of Rights applied to the federal, rather than state governments, thereby helping to further define the line between the two institutions.

Final Years & Death

Marshall spent his final years working on an abridgment of his earlier work, a 5-volume biography of his hero George Washington; the abridgment, intended for use in schools, was published a few years after Marshall's death. In 1831, Chief Justice Marshall went to Philadelphia, where he underwent surgery to remove gallstones. Though the operation was successful, tragedy struck that December when Polly, his wife of 48 years, died; for much of her life, Polly had suffered from debilitating health issues, and Marshall had taken care of her. Marshall did not long outlive his beloved wife. Suffering from health problems of his own, he went to Philadelphia again to seek medical treatment, where he died on 6 July 1835, at the age of 79. One of the last surviving Federalists, Marshall had done much to strengthen the authority of not only the Supreme Court but also the federal government. As such, he is remembered as one of the most important chief justices in the history of the US Supreme Court.