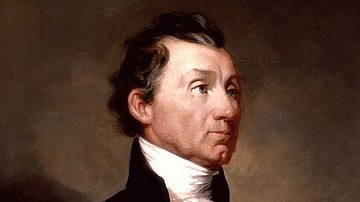

John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) was an American statesman and diplomat who served as the sixth president of the United States (1825-1829). The son of a former president, Adams had a long and distinguished political career both before and after his single presidential term, in which he sought to strengthen the US and advocated for the antislavery movement.

Early Life

John Quincy Adams (pronounced 'Quinzy') was born on 11 July 1767, in his parents' home in Braintree, Massachusetts. His father, John Adams, was then an up-and-coming Boston lawyer who had recently married Abigail Smith Adams, John Quincy's mother. John Quincy grew up amidst the turmoil of the American Revolution, which began practically in his own backyard; indeed, when he was only seven, he witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill from afar. His father was heavily involved in the Second Continental Congress, helping to spearhead the push for the independence of the United States, which was finally achieved in July 1776. In 1778, John Adams was selected to go to Paris as part of a diplomatic mission to secure political and financial support for the Patriot cause. He decided to take John Quincy with him, and, after a tumultuous transatlantic voyage, the Adamses arrived in France in April 1778.

Upon arriving in Paris, John Quincy was sent to a French boarding school, where he quickly became proficient in French. In 1780, when John Adams went to Amsterdam to secure loans from the Dutch Republic, John Quincy accompanied him there as well, furthering his education at Leiden University. During this time, he formed a close relationship with his father, whose personality and political beliefs he came to emulate. Like his father, John Quincy grew into a solitary man with few intimate friends and more comfortable in the company of his books; indeed, around this time, John Quincy began to keep a diary that would become his main confidant over the next 60 years. In 1781, John Quincy parted from his father to go to Saint Petersburg as the personal secretary of Francis Dana, the newly appointed US minister to Russia. He was back at his father's side by 1783, where he acted as an informal secretary during the negotiations that led to the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War and secured British recognition of US independence.

Career Beginnings

In 1785, John Quincy returned to Massachusetts in the hopes of starting a political career. He rounded out his education at Harvard College before going on to study law and finally opened his own legal practice in Boston in 1790. For the next few years, he remained aloof from politics as he worked to build his reputation as a lawyer. But law was a "profession he never loved," as his mother Abigail put it, so when President George Washington offered him the position of ambassador to the Netherlands in May 1794, he accepted. From this vantage, Adams was able to keep tabs on the French Revolutionary Wars that were escalating in Europe, sending information back to the Washington administration; these letters helped convince Washington that the young Adams was one of the most capable American diplomats, earning him the important post of ambassador to Portugal in 1796. Adams spent the winter of 1795-96 in London, where he courted the 20-year-old Louisa Catherine Johnson, daughter of an American merchant and an Englishwoman. John Quincy and Louisa were married in London on 26 July 1797. They would eventually have four children.

By the time of his marriage, Adams' father had been sworn in as the second US president. Ignoring charges of nepotism, President Adams appointed John Quincy as ambassador to Prussia. While in Berlin, John Quincy frequently wrote to his father about developments in Europe, giving the Adams administration key information during the perilous months of the Quasi-War with France. In 1799, John Quincy Adams struck a significant trade deal with Prussia but was recalled to the US the following year, after his father lost re-election to Thomas Jefferson.

Senator & Diplomat

In 1803, the Massachusetts legislature elected Adams to the US Senate. Although he had never been much of a partisan man, Adams went to the new capital of Washington, D.C., as a member of the Federalist Party, like his father before him. However, he quickly broke with his party by supporting the Louisiana Purchase, which had been negotiated by the Democratic-Republican administration of President Jefferson. In December 1807, Adams again crossed party lines by supporting the Embargo Act of 1807, which placed an embargo on Great Britain as punishment for the Royal Navy's impressment of American sailors. Adams' Federalist colleagues opposed the embargo since the Federalist stronghold of New England heavily relied on trade with British merchants, once again earning him their ire. Due to his support for the Embargo Act, Adams lost his Senate seat in 1808, leading him to exit the Federalist Party and join the Democratic-Republicans.

In 1809, President James Madison appointed Adams as the US minister to Russia. He opted to take Louisa with him to Saint Petersburg but left their three children at home to continue their educations – this caused some friction in their marriage, which was worsened when Louisa found Saint Petersburg a cold and unpleasant place. She would eventually warm to the post, however, and became a popular figure at the tsar's court. In 1812, Adams witnessed Napoleon's invasion of Russia, which resulted in the dissolution of the Grande Armée and contributed to the downfall of the French emperor; Adams dutifully reported these developments to Washington.

The same year, the War of 1812 broke out between the United States and Britain in response to the Royal Navy's continued practice of impressment. The war did not begin well for the US, and Adams was soon appointed to a delegation charged with negotiating peace. After several grueling months, the delegation – which also included Albert Gallatin, Henry Clay, James A. Bayard, and Jonathan Russell – finally met with British officials in the Flemish city of Ghent. The diplomats agreed to restore all borders to their prewar state and finalized the peace on 24 December 1814 with the Treaty of Ghent. Then Adams traveled to Paris where he witnessed Napoleon's brief return to power in the Hundred Days of 1815.

Secretary of State

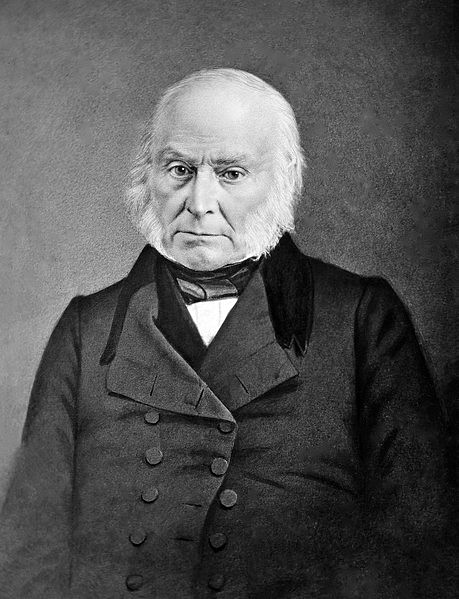

In 1817, Adams was selected to serve as secretary of state by President James Monroe. He would become instrumental in the foreign policy of the Monroe administration, during a period of political calmness known as the 'Era of Good Feelings'. Adams helped mend post-war relations with Britain by overseeing the Treaty of 1818, which fixed the US-Canada border at the 49th parallel, and additionally negotiated the purchase of Florida from Spain in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. In the process of acquiring Florida, Adams supported the aggressive actions of General Andrew Jackson, who had exceeded his authority by capturing the Spanish outpost of Pensacola and executing two Englishmen; Adams convinced Monroe's cabinet that Jackson's actions had been necessary for national defense.

Monroe and Adams supported the Spanish colonies of Latin America in their struggles for independence. Worried that Spain – or another European power – might return to reassert authority over their former colonies, Adams urged Monroe to publicly denounce any European attempt to exert influence in the Americas. This policy was expounded on and eventually became known as the Monroe Doctrine, in which the United States claimed the western hemisphere as its sphere of influence and warned the European powers from meddling in the Americas. Adams contributed greatly to the Monroe Doctrine, which would become a cornerstone of US foreign policy in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

1824 Election

As President Monroe's second term came to an end, several figures came forth as possible successors. Adams, as secretary of state, was a strong contender – it was rumored that he had the support of Monroe himself, though the president stayed silent on the matter. But Adams would face steep competition from Henry Clay of Kentucky, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, and William H. Crawford of Georgia, all of whom commanded much support within the Democratic-Republican Party (the Federalists had lost all national influence after their opposition to the War of 1812, leaving the Democratic-Republicans as the only party strong enough to field presidential candidates in 1824). Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, still riding high from his victory in the Battle of New Orleans, also declared his candidacy, sparking a five-way race.

Calhoun eventually dropped out of the race after both Adams and Jackson promised to take him on as their vice president, and Crawford suffered a serious stroke that significantly diminished his chances of victory. In December 1824, when the electoral votes were counted, it was discovered that no candidate had won a clear majority; Jackson was in the lead with 99 votes, followed by 84 for Adams, 41 for Crawford, and 39 for Clay. As stipulated by the Constitution, the decision was then sent to the House of Representatives. During this time, Clay – who was a fierce critic of Jackson – decided to withdraw from the race and shifted his support toward Adams, which clinched the victory for the New Englander. John Adams, now 88, had lived long enough to see his son elected to the presidency; though he was clearly proud, the elder Adams understood better than most the headaches his son would soon endure. When discussing the matter with well-wishers, the former president said that "no man who ever held the office of president would congratulate a friend on obtaining it" (McCullough, 639). John Adams would die on 4 July 1826, in the middle of John Quincy's presidency.

Presidency

Adams was inaugurated in Washington on 4 March 1825. He was the first son of a former president to also be elected to the office, a distinction that would go unrepeated until the election of George W. Bush almost 180 years later. As diligent as ever, Adams would always rise before dawn to go for a swim in the Potomac River before sitting down to a full day's work. At this point in his life, Adams was nearly 60 years old and had lost his youthful good looks – this combined with his lifelong social awkwardness, he did not cut a charismatic figure and struggled for popularity in Washington. It did not help matters that he had appointed Henry Clay as his secretary of state, leading to an accusation that the two men had made a 'corrupt bargain' during the election, whereby Clay had allegedly supported Adams in return for the State Department. This accusation alienated several important figures from the Adams administration, including Vice President Calhoun.

Despite his tenuous popularity, Adams tried to push forward with his ambitious agenda, which was largely focused on internal improvement projects. He and Clay believed that the country could achieve greater prosperity through the building of better infrastructure and the creation of new institutions like a national university and a naval academy. Their improvement program faced opposition from skeptical congressmen who feared that such federally funded programs would lead to the erosion of state autonomy. As a result, many of Adams' proposed projects were rejected by Congress. The Adams administration had better luck with their proposed infrastructure improvements, securing funds for upgrades to the National Road out of Cumberland, Maryland, as well as for the creation of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Additionally, Adams signed off on the unpopular Tariff of 1828 – known as the 'Tariff of Abominations' – that placed a high protective tariff on certain raw materials like hemp and flax. When European nations responded with retaliatory tariffs on cotton from the American South, Adams became wildly unpopular in the South at a critical moment before the next election.

In terms of foreign policy, Adams and Clay continued to support the newly independent Latin American republics, hoping that by doing so, they could keep them out of Britain's sphere of influence. Adams even hoped to send US representatives to the Congress of Panama, a meeting of American republics hosted by Simon Bolivar. This was resisted, however, by Jacksonians who believed that the United States' attendance at the Congress would go against its current policies of isolationism and neutrality, while racist Southern politicians were horrified by the prospect of attending a meeting at which the Republic of Haiti – still unrecognized by the US – might also attend. The US ultimately did not send representatives to the meeting. Adams also mulled the possibility of buying Texas from Mexico, although he did not end up doing so; later, he would oppose Texas' annexation for reasons relating to the expansion of slavery.

With the end of Adams' term approaching, it was clear that he was going to face a fierce battle for re-election. As early as October 1825, Jackson had accepted the Tennessee legislature's nomination for president and had spent the next three years attacking Adams and Clay. Rather than focus on policy issues, the Jacksonians accused the Adams administration of corruption while emphasizing Jackson's own popularity. Adams' supporters fired back with accusations that Jackson and his wife, Rachel, had had a bigamous relationship in the early years of their marriage, leading the Jacksonians to retaliate with personal attacks against Adams. As the election grew increasingly nasty, it became clear that the 'Era of Good Feelings' was over; American voters and politicians were forced to become either 'Adams men', a faction that would become the National Republican Party, or 'Jackson men', who would coalesce into the Democratic Party. Vice President Calhoun jumped ship and joined Jackson's ticket, leaving Adams to choose Richard Rush of Pennsylvania as his running mate. Ultimately, Adams lost the election; things had become so bitter that he refused to attend Jackson's inauguration in March 1829.

Post-Presidential Career

Upon leaving the White House, Adams returned to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, expecting to begin a quiet retirement. Aside from the disappointment of his election loss, he had recently been beset with personal tragedy: his eldest son, 28-year-old George Washington Adams, had died, likely by suicide, in April 1829 (Adams' second son, John Adams II, would also predecease him in 1834, succumbing to an illness). Despite his grief, Adams' retirement would not last long – in 1830, he was persuaded to run for Congress by the Anti-Masonic Party (a political party that opposed Freemasonry). Although critics argued it was unbecoming for a former president to run for a lower office, Adams retorted that no one could be degraded from serving his countrymen. He won election to the House of Representatives in 1831, thereby beginning a second political career that would last the rest of his life. In 1836, he aligned himself with the new Whig Party, which had emerged in opposition to the Jackson administration.

As a congressman, Adams did much for the improvement of science education in the US and was instrumental in the foundation of the Smithsonian Institution. However, the issue that he aligned himself most with during his final years was the antislavery movement. Adams, whose family had never owned slaves, had always despised the institution and now dedicated himself to the fight against it. In the first half of the 1830s, he constantly presented petitions from citizens urging the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia and even introduced a resolution for a constitutional amendment that would require any child born on US soil after 4 July 1842 to be born free. In 1836, partially in response to Adams' persistence, Southern congressmen passed a 'gag rule' that prevented any legislators from discussing the topic of slavery. Adams spent the next seven years fighting against the 'gag rule' and continued speaking out against slaveholders; the rule was finally repealed in 1844.

Perhaps the most dramatic moment of Adams' fight against slavery occurred in 1841 when he joined the case of United States v. Amistad before the US Supreme Court. In this case, Adams defended the enslaved Africans who had risen up against their captors and seized the Spanish slave ship La Amistad before being apprehended off the coast of Long Island, New York. Adams and his co-counsel argued that the Africans had been kidnapped and enslaved by illegal means and should therefore be set free. The Supreme Court agreed to uphold the ruling of a lower court, which had already decided in the Africans' favor, thereby ensuring their freedom.

Adams opposed the admission of the Republic of Texas into the Union, fearing that it would add to the power of the Southern slave states and lead to a war with Mexico, which still claimed Texas as its own. When the annexation of Texas did indeed lead to the Mexican-American War, Adams opposed the conflict, condemning it as a 'war to expand slavery', and was one of only 14 congressmen (out of 188) to vote against the declaration of war. This opposition continued for the next few years, even after Adams' health began to deteriorate. In 1846, he had a stroke that incapacitated him for several months, though he recovered enough to return to Congress in February 1847. On 21 February 1848, the House was discussing a proposal to honor the Army officers who had fought in Mexico with ceremonial swords. Adams, who still believed the war to have been an evil endeavor, stood up to oppose the motion; immediately after doing so, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and collapsed. He died two days later, on 23 February 1848, in the Speaker's Room in the Capitol Building, at the age of 80.