John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622 CE) was an English merchant and colonist of Jamestown best known as the husband of Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617 CE). He is also known, however, for his successful cultivation of tobacco in Virginia which established the crop as the most lucrative export of the early English colonies of North America.

Tobacco had proven itself a profitable trade commodity for the Spanish who had colonized South and Central America and the West Indies throughout the 16th century CE. The English hoped they would have the same kind of success with their colony at Jamestown, but the settlement struggled for three years just to survive until Rolfe arrived in 1610 CE with tobacco seeds he believed would do well in the marshy soil of Virginia. Rolfe produced his first crop by 1611 CE, not only saving the colony but establishing a cash crop that would form the basis for the colonial American economy.

He married Pocahontas in 1614 CE, a union which forged a peace between the colonists and the Native Americans of the Powhatan Confederacy. The couple had one son and traveled to England on a public relations tour to encourage further investment in Jamestown in 1616 CE. Pocahontas, who had converted to Christianity and taken the name Rebecca by this time, fell ill and died in 1617 CE. Rolfe left his son in the care of his brother and returned to Jamestown where he married his third wife, Jane Pierce, in 1619 CE.

The peace established by his marriage to Pocahontas steadily unraveled as more colonists arrived from England and more land was taken for settlements and tobacco plantations. In 1622 CE, the Second Powhatan War broke out in which over 300 colonists were killed. Rolfe died this same year, but his cause of death is unknown as is his place of burial.

This is the generally accepted version of Rolfe's life but it has been challenged by the Native American Mattaponi oral history which maintains that Pocahontas was raped after she was kidnapped in 1613 CE, became pregnant, that Rolfe only married her to conceal the rape from her father, and that she was murdered (poisoned) aboard the ship in England. These two very different accounts of Rolfe and his relationship with Pocahontas continue to be debated.

Spain, Tobacco, & English Colonization

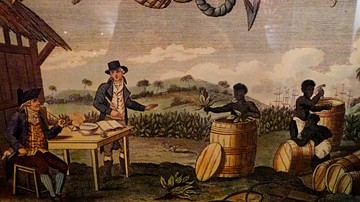

Both versions agree, however, that Rolfe was the "father of tobacco" in the Virginia colonies. There were two types of tobacco that grew naturally in the Americas, Nicotiana rustica (growing mainly in the north) and Nicotiana tabacum (appearing primarily in the south). Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506 CE) claimed the West Indies and parts of South America for Spain following his initial expedition of 1492 CE, and other Spanish expeditionary forces followed, colonizing South and Central America and modern-day Florida throughout the 16th century CE. Columbus had been offered tobacco as a welcome gift by the natives of the West Indies upon his arrival and initiated its commercial cultivation, establishing the system of the encomienda which, basically, enslaved the indigenous population as a labor force.

Nicotiana tabacum was a most profitable export which made Spanish landowners in the Americas and merchants back in Spain wealthy as it quickly found a market and was in high demand. The English wanted to replicate this success and so established the Roanoke Colony in North America in 1585 CE. The first attempt failed and the second, established in 1587 CE, disappeared by 1590 CE. Sir Walter Raleigh (l. c. 1552-1618 CE), who had overseen the expeditions, introduced Nicotiana rustica to England c. 1585 CE and, although it did find a market, it was not as popular as the Spanish product. Tobacco users found Raleigh’s product bitter and difficult to smoke as compared with the smoother and better-tasting Spanish tobacco. The Spanish understood the value of their product and carefully guarded their blend, declaring the death penalty for any Spaniard who shared tobacco seeds or crop with non-Spaniards.

Jamestown & Bermuda

John Rolfe was born the same year Raleigh brought tobacco to the English court. He was the son of John and Dorothea (nee Mason) Rolfe, and his father was, possibly, a merchant. Little is known of Rolfe’s early life except that, by 1608/1609 CE, he was married (possibly to one Sarah Hacker though this seems speculative, his wife's name does not appear on primary documents). He must have had connections with the Virginia Company of London – the coalition of businessmen and investors who had financed the establishment of Jamestown Colony of Virginia – because he was included among the prestigious passengers of the Sea Venture in 1609 CE, a supply ship to Jamestown which also carried its new governor, Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622 CE), the writer William Strachey (l. 1572-1621 CE), and the new chaplain for the settlement, the Anglican priest Richard Buck who was assisted by the then-unknown Stephen Hopkins (l. 1581-1644 CE), later of Mayflower and Plymouth Colony fame.

Jamestown was founded in 1607 CE by an expedition made up largely of aristocrats and unskilled lower-class laborers all (or most) of whom were under the impression that North America was a land teeming with gold one only had to pick up off the ground. This delusion had been encouraged by reports of the Spanish conquests which emphasized the wealth of the New World. Consequently, Jamestown was hardly the great success investors had hoped for because the colonists either had no experience in working the land or were disheartened once they realized there were no heaps of gold waiting for them to gather and devoted their efforts to just trying to survive.

The settlers were disciplined and organized by Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE), a member of the first expedition, but he returned to England in the fall of 1609 CE when he was injured in an accident. Without his leadership, which had also established good relations with Chief Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547-c. 1618 CE, also known as Chief Powhatan) of the Powhatan Confederacy of the region, the colony declined. The winter of 1609-1610 CE came to be known as the Starving Time during which people were forced to eat rats, dogs, horses, and finally corpses just to survive.

The Starving Time was not only caused by the inability of the colonists to raise a substantial crop in the marshlands of Virginia but by the failure of supplies to reach the colony in 1609 CE. The Sea Venture was caught in a storm in July 1609 CE and driven onto the reefs off Bermuda (an event that inspired Shakespeare's play The Tempest). Rolfe and the others spent the next few months on the otherwise uninhabited islands while they built two ships to take them on to Jamestown. During this time, Rolfe’s wife Sarah and their infant daughter, Bermuda, both died. Finally, in May 1610 CE, the ships were ready and sailed to Jamestown.

Rolfe & Tobacco

When they arrived, they found the colony in complete disarray. Sir Thomas Gates declared the colony a failure and ordered the survivors to pack up and prepare to return to England. As they were making their way downriver, however, they were met by another ship carrying the nobleman Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1622 CE) who ordered them about. De La Warr took control of the colony, delegating responsibilities to Gates, and initiated a new policy with the Powhatans which resulted in the First Powhatan War (1610-1614 CE). Rolfe, meanwhile, settled himself on a tract of land and, at first, tried cultivating the native Nicotiana rustica. William Strachey criticized this product as "poor and weak and of a biting taste", and Rolfe had little success with it (Goodman, 134). He had arrived, however, with hybrid Nicotiana tabacum seeds from Trinidad which he experimented with. Scholar Jordan Goodman comments:

From whom Rolfe acquired his seeds is unknown though there was contact between Virginia and Trinidad through English merchants and seamen…Any of the considerable number of English and Dutch traders plying around Trinidad and the Orinoco delta and landing in Virginia could have conveyed the seeds to Rolfe. (135)

It is equally possible the seeds were acquired on Bermuda which had been claimed for Spain by the explorer Juan de Bermúdez (d. 1570 CE) in 1505 CE but never colonized. Spanish ships tended to avoid the islands because they were considered haunted by demons and devils, but it is possible N. tabacum was growing wildly there or that some Spanish ship had left plants there. However he got his hands on the seeds, he perfected their cultivation and had his first crop by 1611 CE.

He named his blend Orinoco (possibly in honor of Sir Walter Raleigh who had explored that region) and exported his first product in 1612 CE; by 1614 CE, he was a wealthy man with a large plantation stretching along the James River across from the settlement of Henricus established by Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560-1619 CE) in 1611 CE.

Marriage to Pocahontas

Lord De La Warr had fallen ill in 1611 CE and installed Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626 CE) with full authority. Argall continued De La Warr’s policies with the Powhatans, and hostilities continued. The Powhatans had taken a number of colonists prisoner and Argall found no means of retrieving them until he learned that the daughter of Chief Wahunsenacah, Pocahontas, was living (possibly with her husband who was later killed) in a nearby village and took her prisoner, holding her for ransom in Henricus. Wahunsenacah returned the captive colonists and expected the release of his daughter but Argall claimed the chief had not fully satisfied the terms of the deal and kept her.

During her time in Henricus, Pocahontas was converted to Christianity, learned English, and came into contact with Rolfe who regularly visited the settlement. The two were attracted to each other and Rolfe wrote to then-governor Dale asking for permission to marry her. The couple were married by Richard Buck in April 1614 CE and their union ended the First Powhatan War and established peace. In January of 1615 CE, their son Thomas Rolfe (l. 1615 - c. 1680 CE) was born and the couple seems to have lived happily on Rolfe’s plantation.

The peace with the Powhatans brought stability which enabled the unencumbered proliferation of tobacco plantations. Goodman notes how "Virginia’s economy exploded into a boom and wherever tobacco could be planted, it was" (135). The secret to Rolfe’s success was the particular blend of his Orinoco tobacco which had a sweet taste whether chewed or smoked and drew easily in a pipe for a much smoother smoking experience than offered by other tobacco.

Journey to England

The Virginia Company, finally seeing a handsome return for its investors, wanted to encourage even more. The company had won support for its charter in 1607 CE by claiming that the salvation of Native American souls was one of its primary goals and now, in Pocahontas, they had a shining example of their success. Rolfe and his family were invited to England in 1616 CE for what amounted to a promotional tour for Jamestown.

The Rolfe party arrived in England in June 1616 CE in the company of the Native American sage (and Pocahontas' brother-in-law) Tomocomo, sent by Chief Wahunsenacah to observe and report back to him on the English in their own country, as well as others from her tribe. The ship was captained by Argall, the same man who had kidnapped Pocahontas years before. The group was escorted to London where Pocahontas was presented as an 'Indian Princess' and was accompanied by Lord De La Warr and his wife to various court functions.

King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) was repulsed by tobacco use and had even written a tract condemning it (A Counterblaste to Tobacco) but could not ban it as the crop was far too profitable. A formal meeting between Rolfe and the king was therefore discouraged since, "Rolfe, as the father of Virginia’s growing tobacco trade, personified one of the king’s vexations: the pipe smoking indulged in by more and more of his subjects" (Price, 177). The party did eventually meet the king (though not formally presented) as well as Queen Anne and other dignitaries.

They also met with Captain John Smith who, according to Smith’s reports, had been saved by Pocahontas when he was taken captive by the Powhatans years before. Smith relates how, in England, Rolfe brought him to Pocahontas who had been told by the colonists in Jamestown that Smith was dead. Upon finding him alive, Smith writes, she said how it was further proof of the lies of the English. Rolfe does not report on this meeting but other accounts corroborate Smith's that it did not seem to have gone well.

Pocahontas is said to have wanted to remain in England, but Rolfe’s business interests were back in Virginia, and he had to return. In March 1617 CE, the party boarded Argall’s ship, the George, for their return, but Pocahontas was feeling unwell. Scholar David A. Price writes:

Rolfe apparently assumed his wife’s affliction was nothing more serious than the sputtering that came and went among so many residents of the polluted city [of London]. By the time the ship was approaching the town of Gravesend, he could see how wrong he had been. Pocahontas was dying. Argall anchored his ship at the town and Pocahontas was taken ashore. (182)

She died soon after and her funeral was held on 21 March 1617 CE. Price notes that "it is generally believed her condition was a pulmonary infection such as pneumonia or tuberculosis" (182). Their son Thomas appeared to be suffering from the same and so Rolfe left him in the care of an official at Gravesend until his brother, Henry, could claim the boy. He then reboarded the ship and sailed back to Virginia; he would never see his son again.

Conclusion

The peace established by Rolfe’s marriage to Pocahontas still held and Argall reported that Chief Wahunsenacah, while lamenting his daughter’s death, was relieved her son still lived and so kept the peace in his honor. Tomocomo had made his report to the Powhatan chief and the elders, denouncing the English and warning they were not to be trusted. According to a report by Thomas Dale, Tomocomo’s claims were disproved by a company of colonists in front of Chief Powhatan, and he was shamed into retracting his statements. In light of the events which followed, however, this report is suspect.

It is more likely that Tomocomo’s charges against the English were taken seriously as tensions began to grow between the colonists and natives of the region. Rolfe continued his life at his plantation and married Jane Pierce, daughter of the militia’s captain William Pierce, in 1619 CE; they had one daughter, Elizabeth. Wahunsenacah died c. 1618 CE, but had already been succeeded by his brother Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646 CE) who recognized that Tomocomo’s words had greater weight than those of the immigrants whose promises and treaties were never kept.

In 1622 CE, Opchanacanough launched a concerted attack referred to by colonial English writers as the Indian Massacre of 1622 CE, killing over 300 settlers and destroying the colony of Henricus. Rolfe’s plantation was directly across from this colony and so it is assumed that he was killed in the massacre, but there is no actual proof of this. Rolfe’s plantation survived the attack, and his wife and daughter were still living in the 1630s CE, Elizabeth dying in 1635 CE, possibly in childbirth.

In this version of Rolfe's life, he is an honorable man, but the Mattaponi oral history paints a very different picture of an opportunist who learned the secrets of tobacco cultivation from the Powhatan chief, married Pocahontas out of necessity, and poisoned his wife to prevent her from informing her father of what she had learned in England. Tomocomo, in this version, tells the Powhatans what Pocahontas did not live long enough to relate. This is another side to the long-accepted version of Rolfe's life written by the victors and is marginalized owing to its challenge to the "official" narrative.

Rolfe is honored in the State of Virginia today through a number of roads and places named after him but, most likely, few who travel these roads know who he was, what he did, or that his tobacco – John Rolfe Blend – is still sold in the present day. He is now best known, at least among a certain demographic, as the husband of Pocahontas (whose image would later appear on cigarette packs and in tobacco advertising) encouraged by an animated straight-to-video Disney sequel to their popular Pocahontas, more than for his contribution to the economy and expansion of Colonial America.

In his time, however, Rolfe was the best-known citizen of the Jamestown Colony, respected by the merchants of London and tobacco aficionados far beyond for his very popular, addictive, and profitable crop. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), tobacco use results in the deaths of 480,000 people per year in the United States, and yet Rolfe’s product continues to be used worldwide and still informs the economy of the State of Virginia as well as that of the United States overall.