Jordan is a country in the Near East bordered by Israel, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. The country's name comes from the Arabic Al Urdun, referencing a fortified site but also meaning "prominence", though various sources also claim the name comes from the Hebrew word Yarad ("descender"), referencing the downward flow of the River Jordan.

The region has a long history as an important trade center for every major empire from the ancient world to the present age (from the Akkadian Empire to the Ottoman Empire), and numerous sites in the country are mentioned throughout the Bible; 180 times in the Old Testament and 15 times in the New Testament.

Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) founded cities in the region (such as Gerasa) and the Nabateans carved their capital city of Petra there from sandstone cliffs. Early in its history, the area attracted and inspired traders, artists, philosophers, craftspeople, and, inevitably, conquerors, all of whom have left their mark on the history of the modern-day country.

Jordan, formally known as The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, has been an independent nation since 1946 after thousands of years as a vassal state of foreign empires and European powers and has developed into one of the most stable and resourceful nations in the Near East. Its capital city, Amman, is considered one of the most prosperous in the world and a popular destination for tourists. The history of the region is vast, going back more than 8,000 years, and encompassing the tale of the rise and fall of empires and the evolution of the modern state.

Early History

Archaeological excavations date human habitation in the region of Jordan back to the Paleolithic Age (around two million years ago). Tools such as stone hand-axes, scrapers, drills, knives, and stone spear points dated to this time period have been found in various locations throughout the country. The people were hunter-gatherers, who led a nomadic life moving from place to place in search of game. In time, they began building permanent settlements and establishing agricultural communities.

The Neolithic Age (c. 10,000 BCE) saw the rise of stable, sedentary communities and the growth of agriculture. These small villages eventually became urban centers with their own industry and initiated trade with others. Large urban centers developed such as the city of Jericho, claimed to be the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world, with an approximate founding date of 9,000 BCE.

According to scholar G. Lankester Harding:

[Cities like Jericho provide evidence of] far higher culture than we had hitherto suspected, for here was not merely a village of well-built houses with fine plaster floors, but there was a great stone wall all around the settlement with a ditch or dry moat in front of it. This implies a high degree of communal organization, of subordinating the personal interests to those of the many.

(29)

Communal interests are also evident in the ancient monuments raised at this time. Throughout the Neolithic Age, the people constructed megalithic dolmens across the land (very similar in size, shape, and methods used to those of Ireland). These dolmens are thought to be monuments to the dead or possibly passageways between worlds. These dolmens are often found in fields of circled stones whose meaning remains unclear, but it is obvious that the builders would have had to work in groups for a common cause to create these sites.

The dolmen sites were most likely religious in nature and visited for worship, divination, and festivals by the people of the nearby cities. The largest settlement of the Neolithic Age in Jordan was Ain Ghazal, located in the northwest (near the present-day capital of Amman). Inhabited c. 7000 BCE, Ain Ghazal was an agricultural community whose artisans created some of the most striking anthropomorphic statuary in early history. The statues found at Ain Ghazal are among the oldest in the world today.

The community had over 3,000 citizens and engaged in trade and the manufacture of pottery, which increased the wealth of the people individually and the city collectively. Ain Ghazal continued as a prosperous settlement for 2000 years between c. 7000 BCE and 5000 BCE when it was abandoned, most likely due to overuse of the land.

The Hyksos & Egyptians

The Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages (c. 4500-3000 and 3000-2100 BCE, respectively) saw further developments in architecture, agriculture, and ceramics. The Ghassulian culture, centered around the site of Talailat Ghassul in the Jordan Valley, rose to prominence in the Chalcolithic Age displaying inordinate skill in smelting copper, ceramics, and intricacies in architectural design.

The Bronze Age settlement of Khirbet Iskander (founded c. 2350 BCE) rose by the banks of the Wadi Wala stream and was a prosperous trading community until the arrival of invaders who destroyed towns, villages, and cities throughout Jordan in c. 2100 BCE. The identity of these aggressors is unknown, but they were most likely the armies of the Gutians whose invasions toppled the Akkadian Empire founded by Sargon the Great (r. 2334-2279 BCE) beginning c. 2193 BCE; the region of Jordan, of course, was part of this empire. The Sea Peoples have been suggested as the invaders by some scholars, but the date is too early for their incursions in the area.

Whoever they were, these invaders were then driven out by another group who migrated to the area (possibly as early as 2000 BCE), the Hyksos, who brought a completely different culture to Jordan and established themselves as the ruling class. In time, the Hyksos of Jordan would amass enough power to conquer Egypt and would hold both countries until driven out by the Egyptians c. 1570 BCE by Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE).

Some scholars argue that the Hyksos (so-called by the Egyptians; the name by which they called themselves is unknown) were indigenous to Jordan while others claim they were foreign invaders; whichever the case, they permanently changed life in Jordan by introducing the horse, composite bow, and chariot to armed conflict, introducing better methods of irrigation, and developing better systems of defense for walled cities.

The region of modern-day Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel (the Levant) were in continuous trade with other areas and civilizations throughout these periods. Writing in Mesopotamia developed c. 3500 BCE as a means of long-distance communication in trade, and yet these regions, which were literate from at least 3000 BCE, did not adopt a system of writing until c. 2000 BCE for reasons which are unclear. Inscriptions such as signs and symbols were created, but no complete script seems to have been formulated. Writing did not develop in Jordan until after the Egyptians had overthrown the Hyksos c. 1570 BCE.

Once the Hyksos were driven out of Egypt, the Egyptians pursued them through Jordan, establishing military posts, which grew into stable communities. Under the later reign of the Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) and her successor Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE), trade flourished. Thutmose III established Egyptian rulers throughout the larger region of Canaan bringing stability, peace, and prosperity. The region flourished to such a great degree that it would be referred to as a glorious land "flowing with milk and honey" centuries later in various books of the Bible.

Jordan in the Bible & the Iron Age

The cities of Gerasa and Gadara (modern-day Jerash and Umm Qais, respectively) are mentioned in the Gospel of Mark 5:1-20 and the Gospel of Matthew 8:28-34. Both of these passages in the gospels relate the story of Jesus Christ driving evil demons from possessed people into a herd of pigs. The story in Mark, considered the earlier of the two, places the event in Gerasa while Matthew's version has it in Gedara. Mark mentions how, after the miracle, the man who had been demon-possessed relates the miracle to all the people of the Decapolis; the Decapolis was the term for the ten cities on the eastern edge of the Roman Empire at that time and both Gerasa and Gadara were among them.

The region of modern-day Jordan is mentioned a number of times in the Bible's Old Testament as part of the narratives which make up the books of Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy, Numbers, Joshua, and others concerning the land of the Israelites, their enslavement in Egypt, and their deliverance to a promised land which then must be conquered. The events related are thought to have occurred during the latter part of the Bronze Age (c. 2000-1200 BCE) although there are discrepancies between the biblical accounts and the archaeological record.

Among the discrepancies most frequently noted by scholars is the fact that the region of Jordan mentioned in the books of Exodus, Numbers, and Joshua is clearly inhabited while the archaeological record indicates a largely unoccupied country. The battles said to have been fought by the Hebrews in Numbers and in Joshua also seem to have left behind no archaeological record. It should be noted, however, that the city of Jericho, famous for its fall to Joshua (Joshua 6:1-27), does show evidence of a violent destruction c. 1200-1150 BCE during the Bronze Age Collapse.

Mount Nebo in Jordan is the spot where Moses is said to have been allowed a glimpse of the Promised Land before he died (Deuteronomy 43:1-4), and Jordan was the land of the Midianites where Moses took refuge after his flight from Egypt in Exodus (Exodus 2:15) and the region in which he encountered the burning bush, which sent him back on his mission to free his people from bondage (Exodus 3:1-17). He is said to be buried on Mount Nebo, originally a site sacred to the Moabites and their gods.

The beginning of the Iron Age (c. 1200-330 BCE) in the region was initiated by the invasion of the Sea Peoples, a mysterious culture whose identity scholars still debate. Some have claimed they are the Philistines of the Bible, while others have suggested they were Etruscan, Minoan, Mycenaean, or other nationalities. No single claim identifying them has been widely accepted nor is it likely one will be in the near future as the extant inscriptions available only state that these people came from the sea, not which sea nor even from which direction.

The Sea Peoples arrived on the coast of Canaan c. 1200 BCE with an advanced knowledge of metallurgy, and their iron weapons were far superior to the stone and copper blades and spears of their opponents. While the Sea Peoples were invading from the south, the biblical record tells of great battles between the Israelites and the Moabites and Midianites in the Book of Judges as well as raids on Israelite settlements by the Ammonites from northern Jordan. The Jordanian kingdoms of Edom in the south, Moab in the center, and Ammon in the north all grew in power during this time.

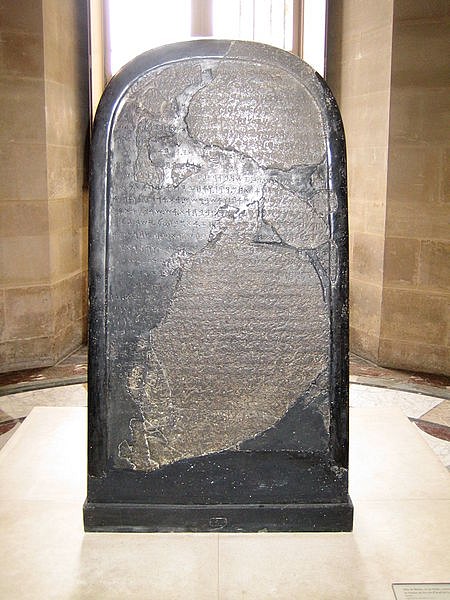

The Mesha Stele (also known as the Moabite Stone, c. 840 BCE) records a battle fought between Mesha, king of Moab, and three kings of Israel. The narrative on the stele corresponds to the account of the event given in II Kings 3 in which Joram of Israel and Jehosophat of Judah go to war to put down a Moabite rebellion. The Mesha Stele is among the best-known artifacts corroborating a biblical narrative, even though some scholars have questioned its meaning and even its authenticity.

The dispute over whether the Mesha Stele supports the biblical narrative is typical of arguments over interpretation not only of objects but also of ancient texts. Those scholars who equate the Sea Peoples with the Philistines interpret the books of I and II Samuel, which significantly feature the Philistines, as a narrative of the Sea Peoples. These books tell the story of the rise of King Saul (c.11th century BCE) over the Israelites and David's defeat of the Philistines in slaying their champion, Goliath, in single combat.

Most of what is known of the Sea Peoples comes from Egyptian records, which claim that they were defeated by Ramesses III in 1178 BCE near the Egyptian city of Xois, and, afterwards, they vanish from the historical record. If this claim, along with Saul's and David's traditional dates, is accepted then the Philistines could be the Sea Peoples who invaded Egypt following their battles with Saul and David. This is far from certain, however, and no consensus on this subject has been reached.

Scholarly agreement is also divided on whether the Sea Peoples were responsible for the devastation of cities throughout the region of Canaan or whether this was the result of the general Joshua and his campaigns of conquest in the region, claiming it as the promised land for his people (books of Numbers and Joshua). Either way, the introduction of iron weapons to the region changed the dynamics of battle, favoring those armed with them, as Assyrian warfare proved when they took the country. The Assyrians were considered invincible in battle; largely due to their superior weaponry.

The Great Empires & The Nabateans

The Assyrian Empire, and its continuation the Neo-Assyrian Empire, both employed iron weapons in conquest and became the greatest and most extensive political power in the world up to that time. Under the Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser I (1115-1076 BCE), the region of the Levant was firmly taken under Assyrian control, and it would remain part of the empire until its fall in 612 BCE.

The Babylonian Empire then took possession of the land until it was taken by Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire (549-330 BCE), also known as the Persian Empire, which then fell to Alexander the Great in 331 BCE and became part of his emerging empire. Prior to Alexander's invasion, a unique culture grew up in Jordan whose capital city has become one of the most recognizable images from the ancient world and a popular tourist attraction in the present day: the Nabateans and their city of Petra.

The Nabateans were nomads from the Negev Desert who arrived in the region of modern-day Jordan and established themselves sometime prior to the 4th century BCE. Their city of Petra, carved from sandstone cliffs, may have been created at this time but possibly earlier. The Nabateans initially gained their wealth through trade on the Incense Routes traveling between the Kingdom of Saba in southern Arabia and the port of Gaza on the Mediterranean Sea. By the time they had established Petra, they were also in control of other cities along the Incense Routes and were able to tax caravans, provide protection, and control the lucrative spice trade.

The famous façade of Petra, known today as The Treasury, was almost certainly originally a tomb or mausoleum and, contrary to popular imagination, does not lead into any intricate maze of hallways but only a fairly short and narrow room. The more spacious dwellings, which make up the rest of the cliff city, attest to the Nabateans' wealth as traders who had enough disposable income and manpower to be able to afford such an intricate and timely construction.

The name 'Petra' means 'rock' in Greek; the city was originally called Raqmu (possibly after an early Nabatean king) and is mentioned in the Bible and in the works of writers such as Flavius Josephus (37-100) and Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE). At the height of the Kingdom of Nabatea, the Jordan region enjoyed great prosperity, and not only in and around the city of Petra. The Nabateans were certainly the wealthiest, but people of other nationalities shared their good fortune as well.

Around 200 BCE, the governor of Ammon, Hyrcanus, had his elaborate fortress-palace Qasr Al-Abd ("Castle of the Servant") built, which would have required a huge amount of disposable income. Flavius Josephus describes the palace (which he understood as a fortress) in glowing terms as "built entirely of white stone" on a grand scale, including a large reflecting pool, and how its walls were carved with "animals of a prodigious magnitude" as well as banquet halls and living quarters supplied with running water (Merrill, 109). Ruins of this structure survive today near Araq al-Amir, although in a greatly diminished state from Josephus' time, but still attesting to the wealth and vision of the man who commissioned it.

The first historically attested king of the Nabateans was Aretas I (c. 168 BCE), and so, although the Nabateans had established themselves in the region centuries before, the Kingdom of Nabatea is dated from 168 BCE to 106 CE when it was annexed by Rome. The Nabateans had a highly developed culture in which art, architecture, religious sensibilities, and trade all flourished. Women had almost equal rights, could serve as clergy, and even reign as autonomous monarchs. The most important deities of the Nabatean pantheon were female, and women most likely would have served as their high priestesses.

To solve the problem of a reliable water supply in the arid region, the Nabateans engineered a series of wells, aqueducts, and dams whose efficiency was unrivaled in their day. With access to water, and established in some of the most inaccessible areas of the region, the Nabateans were able to fend off aggressors attracted by their wealth. They could not hold out long against the superior might of Rome, however, which steadily took their territories and absorbed their trade routes until finally taking the entire kingdom and renaming the region Arabia Petraea in 106 CE under the Roman emperor Trajan (r. 98-117).

Rome, Islam, & the Modern State

The Romans revitalized much of the region (although Nabatean cities such as Petra and Hegra were neglected), creating a powerful trade center at Gerasa and another called Philadelphia at the site of Ammon, now Amman, the capital city of modern-day Jordan. The city of Gedara flourished under the Romans. Gedara was the birthplace of the Roman poet and editor Meleager (1st century) and had earlier inspired the work of the Epicurean philosopher and poet Philodemus (c. 110-35 BCE). The Romans certainly benefited from the resources of the region, as well as from the recruits they pressed into their armies as conscripts and auxiliaries, but also improved the area as they built roads, temples, and aqueducts which turned large areas of the region into fertile landscape and encouraged prosperous trade. Gerasa became one of the wealthiest and most luxurious provincial cities of the Roman Empire at this time.

Even so, Rome began to decline steadily with the Crisis of the Third Century and faced serious challenges as the 4th century began. As Rome struggled with internal difficulties and invasions, the region that would become Jordan suffered along with all the other provinces. The semi-nomadic Tanukhids gained power in and around the area in the 3rd century, and their most famous leader, Queen Mavia (c. 375-425) led a revolt against Rome, most probably provoked by the empire's insistence on Tanukhid auxiliaries for the Roman army.

As the Tanukhids were originally part of the Nabatean tribal confederacy, it is thought she would have controlled the areas formerly comprising the Kingdom of Nabatea. Whether this is so, she was powerful enough to defy Rome, negotiate a peace on her own terms, and later send cavalry units to assist in the defense of Constantinople following Rome's defeat at the Battle of Adrianople in 378.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476), the eastern part continued as the Byzantine Empire, ruling from Constantinople. In the 7th century, the Arab invasion swept across the region, converting the people to Islam, which then brought these people into conflict with the Byzantines. The region of modern Jordan became a part of the Umayyad Empire, the first Muslim dynasty, which ruled from 661 to 750. Under the Umayyad Dynasty, Jordan thrived but was neglected by the next ruling house, the Abbasid Dynasty (750-1258) when they withdrew their support from the area, moving the capital from Damascus, just north of Jordan, to Kufa and then Baghdad, significantly further away.

The Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171), which was absorbed by the Abbasids, took Jordan during their expansion and initiated renovations of temples, buildings, and roads, as did the Ottoman Empire (1299-1923), which came after the Abbasids. The Ottoman armies defeated the forces of the Byzantine Empire, ending Western influence in the region in 1453: the fall of Constantinople

During the First World War (1914-1918), the Ottomans sided with Germany and the Central Powers. The Arab Revolt of 1916, which started in Jordan, significantly weakened the Ottoman Empire as it struggled against the Allied Powers, and, when they were defeated, the empire was dissolved in 1923. Jordan then became a mandate of the British Empire until it won its independence in 1946 following the Second World War (1939-1945). Today the region is known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, an autonomous state with a bright future and a long and illustrious past.

Grateful acknowledgement to Mr. Adi Abbadi of Jordan History for his assistance in the revision of this piece.