Doctor Joseph Warren (1741-1775) was a physician from Boston, Massachusetts, who became an important political leader of the Patriot movement during the early years of the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789). Known for dispatching Paul Revere on his midnight ride and for his premature death at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Warren is considered a Founding Father of the United States.

Early Life

On 11 June 1741, Joseph Warren was born in the town of Roxbury, located just across from Boston, in the British colony of Massachusetts Bay. The eldest of four brothers, he was the son of Joseph Warren, Sr., a farmer, and Mary Stevens Warren; young Joseph would often accompany his father on his trips to Boston. A responsible, charismatic, and highly intelligent boy, Joseph excelled in his studies at the Roxbury Latin School and was enrolled in Harvard University in 1755, aged just 14. In October of that same year, Joseph Warren, Sr., was picking apples when he fell from atop a tall ladder. The fall broke his neck, killing him instantly. Joseph, Jr., was now responsible for the care of his mother and younger brothers, a burden made a little more bearable thanks to the financial contributions of family friends.

Warren did not let the death of his father, and the extra responsibilities that came with it, dampen his Harvard experience. He staged multiple performances of the popular play Cato in his dorm room, was an active member of the university's militia, and may even have been a member of a club of medical students who raided graveyards and jails in search of cadavers to practice operating on. In his book Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution, author Nathaniel Philbrick tells an anecdote from Warren's Harvard days that showcases his determined personality and thrill-seeking nature:

A classmate later told the story of how Warren responded to being locked out of a meeting of fellow students in an upper-story dormitory room. Instead of pounding at the door, he made his way to the building's roof, shimmied down a rainspout, and climbed in through an open window. Just as he was making his entrance, the rotted spout collapsed to the ground with a spectacular crash. Warren simply shrugged and commented that the spout had served its purpose. For a boy who had lost his father to a fatal fall, it was an illustrative bit of bravado. This was a young man who dared to do what should have, by all rights, terrified him (144).

After graduating in 1759, Warren taught for a year at Roxbury Latin School before beginning to practice medicine and surgery in Boston. In 1764, during a smallpox epidemic, 23-year-old Warren worked with a team of doctors to inoculate about 5,000 people who had been quarantined on Castle William in Boston Harbor. He treated Bostonians from all walks of life, including the lawyer John Adams and the sons of Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, helping Warren to quickly become one of Boston's most well-known and well-respected physicians. That same year, Warren married 18-year-old heiress Elizabeth Hooten; the couple would have two sons and two daughters before Elizabeth's untimely death in 1773. Warren appears to have been a man who enjoyed the finer things in life since, by the time of his wife's death, he had blown through almost all of her considerable dowry. By now, Warren had developed a reputation as a respected physician and charming widower, but as the winds of revolution blew in from across the harbor, Warren would soon be whisked into a new position as a leader of a political movement.

The Revolutionary

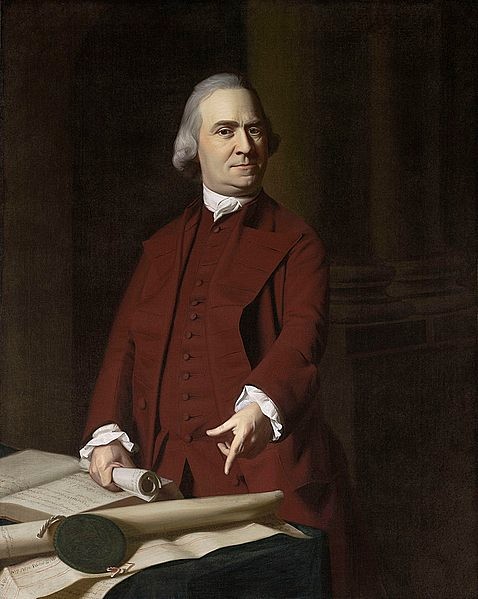

It was through Dr. Warren's profession that he became introduced to the men who would change not only his life but also the course of American history. John Hancock was the wealthiest merchant in New England, whose ambition and flashy lifestyle was encapsulated by his grand mansion atop Boston's Beacon Hill. Samuel Adams, on the other hand, was an unsuccessful businessman constantly on the verge of poverty, but whose charismatic tongue and skill with a pen would soon put him at the forefront of the revolutionary movement. Warren likely became acquainted with Hancock, Adams, and other prominent Bostonian Whigs around 1765, the year that the British Parliament enacted the Stamp Act.

The Stamp Act was Parliament's attempt to get Britain's thirteen North American colonies to help pay off the debt that the British Empire had incurred while fighting the Seven Years' War, which had ended two years before. The act required the colonists to pay a tax, represented by a stamp, on all paper documents they purchased. While the tax itself was not particularly burdensome, many Americans objected to the Stamp Act on the basis that Parliament had no right to directly tax them.

When the colonists' ancestors first crossed over to the New World, the argument went, they had carried their 'rights as Englishmen' with them, rights that were enshrined in both the British constitution and in their own colonial charters. One of these rights was for the people to tax themselves; since no Americans were represented in the British Parliament, Parliament had no authority to tax Americans. Samuel Adams was one of the loudest dissenting voices to the Stamp Act, arguing that if the Americans paid the tax, they would be consigning themselves "from the status of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves" (Schiff, 73).

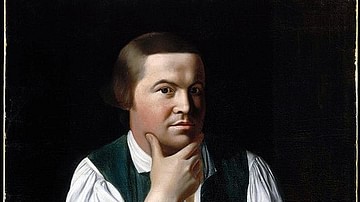

On 14 August 1765, a Boston mob hanged one of the new stamp officials in effigy before raiding his home; the stamp official resigned the next day, and the tree from which the effigy had been hanged was dubbed the Liberty Tree. Although Warren did not participate in the Stamp Act riots, he certainly witnessed them, and was given his first taste of revolutionary fervor. In early 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, but the colonists barely had time to celebrate before the passage of the Townshend Acts in 1767, taxes that were considered equally oppressive by the colonists. By now, Warren's position as an esteemed member of the Boston community had allowed him to integrate further into the town's Patriot faction. He became closely involved with the underground group of political agitators known as the Sons of Liberty. In particular, the doctor struck up a close friendship with one member of the group, a silversmith named Paul Revere.

In 1768, Warren entered the political arena for the first time, writing a series of articles for the Boston Gazette that lambasted the Townshend Acts; the articles were written with elegant yet fiery prose and were signed 'A True Patriot'. Warren's words were so incendiary that the royal governor attempted to charge Warren and his publishers with libel, but a grand jury refused to move forward with the charges. That same year, riots again erupted in Boston after British officials tried to seize the Liberty, a sloop belonging to Hancock; the British responded to the riots by sending in soldiers on 1 October 1768, who began setting up camp on Boston Common. Warren had chosen a precarious time to thrust himself into politics, but found that he liked the thrill; he would soon find himself one of the most revolutionary men in America's most revolutionary town.

Rising Star

By the spring of 1770, the British occupation of Boston had been ongoing for nearly a year and a half; all that time, tensions had been rising between the soldiers and the town's residents. On 22 February 1770, a crowd of Bostonians, mainly consisting of young boys, gathered in protest outside the home of a customs official and Loyalist; claiming that he feared for his life, the Loyalist fired into the crowd, killing 11-year-old Christopher Seider. Dr. Warren performed the autopsy on young Seider, whose murder inflamed Boston's population, leading another crowd to harass a group of British soldiers several days later on 5 March. The soldiers opened fire on the crowd, ultimately killing five colonists and wounding another six.

Like many of his fellow Bostonians, Warren responded with rage to the Boston Massacre. Alongside two other Sons of Liberty, James Bowdoin and Samuel Pemberton, Warren served on a committee that collected affidavits from the massacre to aid the prosecution of the British soldiers. The committee decided to publish the affidavits as A Short History of the Horrid Massacre in Boston, an account that was entirely as propagandistic as its title suggests; the account emphasizes the aggression of the British soldiers in the days leading up to the massacre while presenting the citizens of Boston as peaceful and law-abiding. This became the best-known account of the Boston Massacre, heavily influencing public opinion around the event; despite this, most of the accused British soldiers were acquitted at trial, brilliantly defended by Warren's patient and friend John Adams.

Warren's work on the Boston Massacre committee greatly increased his public profile as a Patriot; he became closely associated with Samuel Adams, who became something of a mentor to Warren. On 16 December 1773, members of the Sons of Liberty dumped 342 crates of British East India Company tea into Boston Harbor to protest the recent Tea Act. Warren and his friend Paul Revere were amongst those who had organized a guard to ensure that the tea was not unloaded in the days leading up to the so-called Boston Tea Party, while Warren later worked with Sam Adams to justify the protest to the other colonies. In 1774, Parliament responded by issuing a series of punitive policies known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts. These included the closure of Boston's port to commerce, the installation of British General Thomas Gage as Massachusetts' military governor, and the replacement of many of the colony's public servants with royal appointees. The Intolerable Acts were condemned throughout the colonies as an attack on American liberties.

In August 1774, Samuel Adams, John Adams, and John Hancock left for Philadelphia to attend the First Continental Congress, a meeting of delegates from twelve of the Thirteen Colonies to discuss a unified response to the Intolerable Acts. Warren remained in Massachusetts, where he took a leading role in penning the Suffolk Resolves; this called on the colony's local militias to begin preparing for a potential conflict with British troops. Warren sent Revere to deliver the Suffolk Resolves to the Continental Congress, whose first order of business was to approve them. When Hancock and the Adamses returned from the Continental Congress in late October, they joined Warren and other Massachusetts Patriots in the town of Concord where they formed the Provincial Congress, a provisional American government meant to counterbalance General Gage's military government. Warren played an active role in preparing the colony's militias and procuring arms and gunpowder.

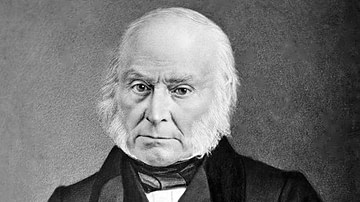

During all this time, Warren had been continuing his work as a physician; he mended the broken hand of young John Quincy Adams, the future sixth president of the United States, who later credited Warren with his ability to hold a pen in that hand. Warren had also struck up a passionate affair with Mercy Scollay, a 33-year-old former patient of his; by the end of 1774, their relationship was amongst the most talked about in Boston, and, by early 1775, they were engaged.

Lexington & Concord

On 5 March 1775, the fifth anniversary of the Boston Massacre, Warren gave a speech to a crowd gathered in Boston's Old South Meetinghouse; harkening back to the days when he would stage plays in his Harvard dorm, Warren gave the speech in a toga to call to mind the liberties of the ancient Roman Republic. After dramatically describing the grieving families of the massacre's victims, Warren announced that:

An independence of Great Britain is not our aim. No, our wish is that Britain and the colonies may, like oak and ivy, grow and increase in strength together…but if these pacific measures are ineffectual, and it appears that the only way to safety is through fields of blood, I know you will not turn your faces from your foes but will, undauntedly, press forward, until tyranny is trodden under foot and you have fixed your adored goddess Liberty…on the American throne (Philbrick, 203).

Warren's words bespoke a conflict that would soon rear its head. By March 1775, rebellion hung heavy in the air above Massachusetts; to postpone a conflict for as long as possible, British General Gage sent troops into the countryside to confiscate stores of arms and ammunition, to prevent their use by the colonial militias. In the early hours of 19 April 1775, an expedition of 700 British troops was dispatched along the road to Concord, where one such store was known to be kept. Gage had wanted to take the colonists by surprise, but his intentions had been leaked to the Americans several days before; on the evening of 18 April, Warren dispatched Revere and another man, William Dawes, along the road to Concord to alert the militias that the regulars were coming.

Revere's famous midnight ride allowed some 70 militiamen to confront the British soldiers on Lexington Green at around 4:30 a.m. on 19 April; during the standoff a shot rang out, leading the British to fire two volleys into the colonists, killing eight and wounding another ten. The British continued on to Concord only to find that the Americans had hidden most of the supplies. On their way back to Boston, the British were harassed by steadily growing numbers of colonial troops. Not wanting to be left out of the action, Warren arrived at the fighting and was nearly killed when a bullet passed through his hair. The Battles of Lexington and Concord resulted in 273 British casualties and 95 American losses; the British retreated into Boston, which was surrounded by over 15,000 colonial militiamen by the next morning. The Siege of Boston, the first major military operation of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), had begun.

Bunker Hill & Death

Shortly after Lexington and Concord, Hancock and the Adamses departed for Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress. On 2 May 1775, Warren was elected to the presidency of Massachusetts' Provincial Congress in Hancock's place; at only 33, he was the most important revolutionary leader in Massachusetts and in charge of the war effort. As he oversaw the siege, he was faced with the daunting task of procuring enough gunpowder and artillery, both of which the colonial army was severely lacking. He struck up a friendship with a Connecticut soldier named Benedict Arnold, whom he dispatched with some troops to seize Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain; Arnold was ultimately successful, though the artillery from Ticonderoga would not arrive in Boston until February 1776.

On 15 June 1775, the colonial army received word that the British intended to fortify the strategically valuable position on Dorchester Heights, from which point they could sweep the Americans out of the towns of Roxbury and Cambridge and end the siege. The Provincial Congress decided to preempt this move by seizing and fortifying Bunker Hill, on the Charlestown peninsula to the north of Boston. On the night of 16 June, 1,200 colonial troops under General Israel Putnam and Colonel William Prescott set out for Charlestown; but rather than fortifying Bunker Hill as directed, they began digging in on Breed's Hill, a position closer to Boston. When the British noticed this movement the next morning, they had no choice but to respond. After a morning cannonade, 2,400 British troops under General William Howe landed at Charlestown to chase the Americans from their position.

By this point, Dr. Warren had been appointed major general by the Continental Congress and was awaiting the arrival of his commission. But he was eager to join the fighting; leaving his surgical duties to one of his apprentices, Warren set out alone for Charlestown. There, he procured a musket from a wounded colonial soldier and presented himself to General Putnam, offering to serve as an infantry private. He then set out to join the soldiers defending the redoubt on Breed's Hill; he must have been quite a sight to the dirty and sweat-stained colonial troops, since Warren was dressed in "a light cloth coat with covered buttons worked in silver, his hair was curled up at the sides of his head and pinned up" (Philbrick, 420).

Around mid-afternoon, the British made two advances up Breed's Hill; each time, the colonists waited until the last moment to deliver devastating lead volleys, resulting in heavy British casualties and forcing them back down the hill. On the third attempt, the British managed to storm the redoubt, scattering the American defenders and killing those who refused to flee. Warren, who may have been one of the last Americans to leave the fortification, was killed instantly by a shot between the eyes. He was recognized by the British soldiers, who bayoneted his corpse several times and stripped him of his fancy clothes. His decomposing, naked body was found several months later by his brothers and Paul Revere, who identified him by his set of false teeth.

Legacy

Warren became a martyr for the American cause, and his death was lamented across the colonies. The loss of his energetic service was strongly felt; in 1782, one man even stated his belief that, had Warren lived, George Washington would have been "an obscurity" (Philbrick, 481). Warren left behind four children; in 1778, Benedict Arnold gave them each $500 for their education and petitioned Congress to pay them a major-general's pension. Although he died before the American Declaration of Independence, Warren's contribution to the American Revolution has earned him recognition as a Founding Father of the United States. Many modern American towns and counties are named in his honor.