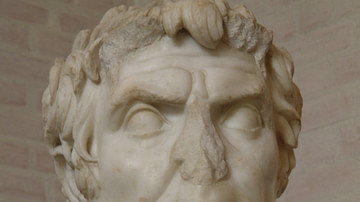

Jugurtha (r. 118-105 BCE) was King of Numidia in North Africa and grandson of the first Numidian king Masinissa (r. c. 202-148 BCE). He was the illegitimate son of Mastanabal, Masinissa's youngest son, and was the least likely of Masinissa's grandsons to ever come to power. His personal ambition, intelligence, and ruthlessness, however, coupled with a keen insight into human motivation and enough finances to buy influence, brought him to power following the death of his uncle Micipsa (r. 148-118 BCE) who had succeeded Masinissa.

Micipsa had divided the kingdom between his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and his adopted son Jugurtha, but Jugurtha assassinated both. He bribed the Roman senate and the various envoys and generals sent against him until in 105 BCE, after a number of stunning defeats at the hands of Roman generals, he was finally betrayed and handed over to the Romans by his son in law, Bocchus, the king of neighboring Mauretania. He was brought back to Rome in chains and died in prison - either executed or by starvation - in 104 BCE.

The most comprehensive account of Rome's war with Jugurtha is that of the historian Sallust (c. 86- c. 35 BCE) but he was very purposefully writing to condemn the avarice and lack of integrity in Rome and chose Jugurtha's story to drive home his point. His version of events, therefore, has often been challenged by modern historians who claim his work is more of a polemic than a history.

Strangely, though, other ancient historians writing on the Jugurthine War such as Plutarch (46-120 CE) and Cassius Dio (155-235 CE), who present more or less the same picture of the man and the conflict he initiated, are generally accepted even though both these writers would have drawn largely on Sallust's account of Jugurtha's rise and fall. As Sallust presents by far the most complete version of Jugurtha's story (which these later writers largely just repeat) and we have no viable, less problematic alternative sources, his work will mostly inform the present article.

Youth & Rise to Power

Masinissa (of the region of Numidia) had initially fought for Carthage during the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) between Rome and Carthage but then switched sides, once he realized Carthage would lose, and became a staunch ally of Rome. When the Romans won the war, Masinissa was rewarded with all the territory in North Africa he had won during the conflict and was more or less given free rein to take whatever he wanted from Carthage.

He founded the Kingdom of Numidia (which roughly corresponds to parts of modern-day Algeria and Tunisia), comprised of these fertile territories, and supplied Rome with grain. Once trade with Rome was established it continually enriched his treasury in the capital city of Cirta.

When he died, he was succeeded by his son Micipsa whose younger brother, Mastanabal, had an illegitimate son whose natural talents and intelligence were noted by all: Jugurtha. Sallust writes:

As soon as Jugurtha grew up, endowed as he was with physical strength, a handsome person, but above all with a vigorous intellect, he did not allow himself to be spoiled by luxury or idleness but, following the custom of that nation, he rode, he hurled the javelin, he contended with his fellows in foot-races; and although he surpassed them all in renown, he nevertheless won the love of all. Besides this, he devoted much time to the chase, he was the first or among the first to strike down the lion and other wild beasts, he distinguished himself greatly, but spoke little of his own exploits (The Jugurthine War, 6.1)

As Sallust goes on to say, Micipsa was initially pleased with the success and popularity of his nephew until he reflected on the possibility that Jugurtha could become a threat to himself and his two sons. In an attempt to resolve the problem, he gave Jugurtha a commission to command the cavalry divisions he was sending to Spain to support the Romans in their engagement with Numantia. He was hoping, as Sallust writes, that Jugurtha “would easily fall a victim either to a desire to display his valor or to the ruthless foe” (7.2). Sallust continues:

But the result was not at all what he had expected; for Jugurtha, who had an active and keen intellect, soon became acquainted with the character of Publius Scipio, who then commanded the Romans, and with the tactics of the enemy. Then by hard labor and attention to duty, at the same time by showing strict obedience and often courting dangers, he shortly acquired such a reputation that he became very popular with our soldiers and a great terror to the Numantians. (7.3-4)

When the war against Numantia was won, Scipio sent Jugurtha home to Cirta with a letter of recommendation praising him highly and with the not so subtle hint that Micipsa should adopt him as son and heir; which Micipsa quickly did. At the ceremony, or soon after, Micipsa asked Jugurtha to care for his cousins as though they were his own blood brothers, which he agreed to, but nothing in the account suggests that he ever meant to keep his promise. Jugurtha had spent his youth in physical pursuits and warfare while Hiempsal I and Adherbal had been raised in the comfort of the palace and, besides, were considerably younger than he was and do not seem to have earned his respect.

Neither was he respected by the cousins, as became evident when their father died. Micipsa had requested that all three should rule the kingdom jointly but, at the first meeting of the princes, Hiempsal took the seat of honor and rebuffed Jugurtha. When Jugurtha suggested that their first step in joint rule should be to rescind Micipsa's edicts of the past five years – because the king had been in failing health and not of sound mind – Hiempsal agreed, saying how that would also nullify Jugurtha's adoption and claim to power. Shortly after this, Jugurtha had Hiempsal assassinated at his home. Adherbal fled for safety and mobilized an army while swiftly sending envoys to Rome to inform the Senate of Jugurtha's actions and ask for help.

Adherbal had the majority of the people on his side but Jugurtha, because of his military accomplishments, had the better soldiers. When Adherbal met Jugurtha in battle, he was quickly defeated and fled the field. He left Numidia for a Roman province which had been established in territory taken from Carthage and, from there, took ship for Rome to plead his case to the Senate, this time in person.

Jugurtha & Adherbal

Jugurtha had made many friends among the Romans in Spain and had come to understand that gold could buy all kinds of grace; he therefore sent envoys with gifts to the Roman senators who were his friends as well as to others who soon would be. Scholar Philp Matyszak comments:

Jugurtha had learned more than soldiering in Spain. He knew that success or failure in Rome depended on holding office and that elections to even the lowest magistracies were phenomenally expensive. Adherbal came to Rome with right on his side and a plea for justice. Jugurtha's envoys came with gold. To the indignation of unbribed Romans, Jugurtha obtained a decree that divided the kingdom between himself and Adherbal, with Jugurtha awarded the richer part. (65)

Although this claim has been challenged, and some scholars insist that Jugurtha's territory was equal in wealth and resources to that of Adherbal, Sallust's account supports the argument that Jugurtha was given the better part of the kingdom. Further, whether he was or not, the Senate refused to censure him in any way for the assassination of Hiempsal or his unprovoked attack on Adherbal. Jugurtha had been sure that enough gold could buy him a favorable decision and it turned out that he was right.

Now as ruler of his own kingdom, Jugurtha consolidated his power and then attacked Adherbal's territory. Adherbal and his supporters were driven back and took refuge in the walled city of Cirta. Jugurtha followed and mounted a siege. Adherbal sent more envoys to Rome asking for help and reporting on Jugurtha's hostilities.

Envoys from Rome were sent to mediate but met only with Jugurtha, never with Adherbal. Jugurtha refused to call off the siege or cease the hostilities in any way and, after most likely receiving a large bribe, the Roman envoys took ship back to Italy.

The defenders of Cirta, realizing they had been abandoned by Rome, had no choice but to seek terms of surrender. They did not have enough food or water to withstand a long siege and seem to have felt confident that Jugurtha would honor whatever terms he gave them; he offered them only their lives in return for the city. Once the defenses were dropped, however, Jugurtha ordered his men to kill every adult found armed within the city walls and had Adherbal tortured to death.

King Jugurtha

Among the defenders of Cirta were a number of Italians who, according to Sallust, had encouraged Adherbal to surrender believing that they would be spared and sent home; they were not. When news of the massacre at Cirta reached Rome, the Senate – however reluctantly – was forced into action. They are depicted by Sallust as dragging out the discussion on whether to send forces against Jugurtha because so many of them had been bribed; Sallust refers to these senators as “tools of the king”, writing:

When this outrage became known at Rome and the matter was brought up for discussion in the senate, those same tools of the king, by interrupting the discussions and wasting time, often through their personal influence, often by wrangling, tried to disguise the atrocity of the deed. (27.1)

No matter how they tried, however, there was no spinning of the event which could alter the fact that Jugurtha had murdered a sitting monarch who was an ally of Rome as well as the Italian defenders of Cirta and non-combatants. The Senate declared war on Numidia in 112 BCE and Lucius Calpurnius Bestia was chosen to lead the Roman forces against Jugurtha in c. 111 BCE.

When Jugurtha heard this news he was shocked, since he believed that money could buy anything from the Romans, and quickly sent his son and some envoys to Rome with even more money since it was clear to him that he must not have sent enough. Although it seems that Bestia was tempted to receive these envoys, the Senate sent word that, unless the Numidian delegation was coming to announce Jugurtha's unconditional surrender, they should go home.

Bestia then had no choice but to lead his troops to battle in North Africa. He began his campaign vigorously, defeating Jugurtha's forces and capturing towns and strongholds. Jugurtha checked his advance, however, not by force but by bribery. He met with Bestia and pointed out how there was no need for a protracted and costly conflict, more or less claiming “what's done is done”, and promised his submission to Roman authority, a sum of over 30 elephants, and a significant amount of cash – in addition to whatever he may have paid to Bestia's personal accounts.

Bestia recalled his troops and returned to Rome, leaving only a token force behind. The commanders of these troops, who also seem to have been bribed by Jugurtha, then returned him the elephants and also sold a number of the deserters from the Roman ranks to him. Bestia claimed that, with the many other troubles Rome was facing, he had won them peace with Jugurtha without an expensive war.

The people of Rome and some members of the Senate, however, were not pleased with this outcome and an investigation was launched into who and how many high-ranking officials were in Jugurtha's pay. Jugurtha was summoned to appear in Rome before the Senate to give testimony and was promised safe-passage and immunity throughout his stay.

Jugurtha complied but, before his testimony could be taken, one of the tribunes, Gaius Baebius, stepped forward and forbade him to speak. The general public who had gathered to watch the proceedings were outraged and tried to shout him down but he used his influence to prevent Jugurtha's testimony and nothing came of the inquisition.

Another of Masinissa's grandsons, Massiva, who had been petitioning the Senate for support to make himself king of Numidia after they had dispensed with Jugurtha, was in Rome watching these proceedings. Jugurtha found where Massiva was staying and had him assassinated. When confronted, he openly confessed to what he had done but did not feel that it was any of Rome's business and, besides, he had been promised immunity during his visit and there was nothing they could do to him. The impotent Senate had no option but to request he leave Rome and Italy instantly.

The Jugurthine War

Jugurtha's insolence and audacity could no longer be tolerated and so an army under the general Postumius Albinus was sent to North Africa to deal with him in 110 BCE. Albinus had been among those in Rome favoring the late Massiva and had no love for Jugurtha but, for one reason or another, made no significant advances against him. He had to return to Rome for elections and left his command to his brother Aulus.

Aulus marched against Jugurtha but the Numidian king called for a parley and hostilities were halted; Jugurtha then delayed and interrupted negotiations until nearly the end of the campaigning season. Recognizing that he would soon have to return to Rome having accomplished nothing, Aulus mobilized his men to attack the town of Suthul where, he had heard, Jugurtha stored an immense amount of his treasure.

Jugurtha had spies everywhere, however, and heard of Aulus' plans. He drew up his army and struck quickly at the Roman camp, scattering Aulus' army. Those who were not killed in the initial onslaught had no choice but to surrender.

Jugurtha then ordered each of the defeated soldiers and their commanders to “pass under the yoke” – a symbolic ritual acknowledging the superiority of one's opponent – and then gave them less than two weeks to leave his kingdom or be killed.

His attack on the Roman camp – and then the humiliation he imposed on the defeated troops – enraged the Roman people and the Senate. It seems that Jugurtha thought he could buy his way out of whatever consequences were coming but, this time, he was wrong.

Rome sent the general Quintus Caecilius Metellus (later given the epithet Numidicus, c. 109 BCE) against him with an impressive force. Metellus was well-known for his integrity and could not be bought but Jugurtha still held to the belief that anything of Rome could be purchased for the right price. He therefore sent envoys to negotiate. Cassius Dio writes in his History:

When Jugurtha sent a message to Metellus in regard to peace, the latter made many demands upon him, one by one, as if each were to be the last, and in this way got from him hostages, arms, the elephants, the captives, and the deserters. All of these last he killed; but he did not conclude peace since Jugurtha, fearing to be arrested, refused to come to him. (26.89)

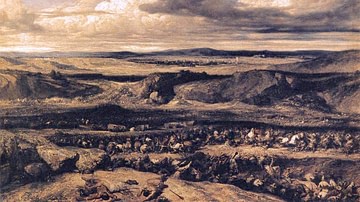

Metellus then struck with full force at Jugurtha, taking the city of Vaga and then defeating him at the Battle of the Muthul in 108 BCE. Jugurtha tried to rally and regroup afterwards but many of his soldiers now felt they had more than done their duty for the king and retired to their homes. Jugurtha then sent envoys to Metellus to again try to negotiate a peace but, each time, Metellus turned these men to his own cause and sent them back to try to assassinate Jugurtha. Matyszak writes:

There was a certain irony in the situation: the man Jugurtha could not corrupt was using his own weapons of corruption, deceit, and delay against him. For the rest of his life, Jugurtha could trust no one and every close aide was a potential assassin. The atmosphere of fear and suspicion that resulted caused many of Jugurtha's closest advisors to desert him before they too were accused of plotting against their leader. (69)

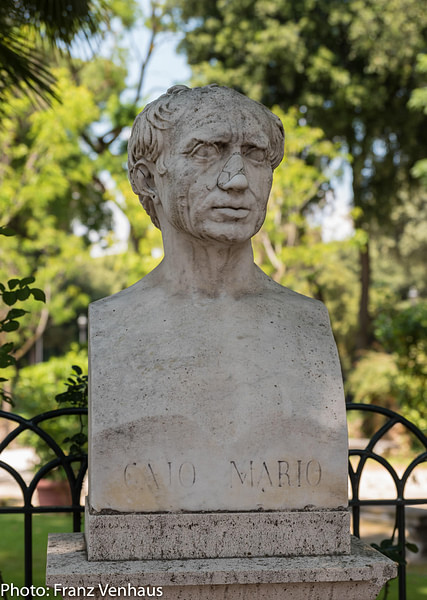

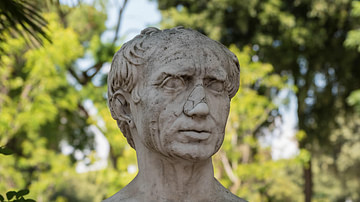

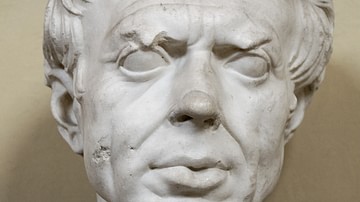

Metellus continued his campaign, taking one city after another, and even re-taking the city of Vaga which Jugurtha had managed to win back. At Thala, Jugurtha was defeated again, losing more territory, arms, and men to Metellus, and the Roman commander would have no doubt pressed on to complete victory but was replaced at this point by his second-in-command, Gaius Marius (c.107 BCE), who was ambitious at Metellus' expense and accused him of drawing out the war unnecessarily. Although the ancient historians are unanimous in praising Metellus' conduct to Marius' detriment, Marius proved to be an excellent general who chose to cripple Jugurtha by systematically reducing his cities and draining his resources rather than meeting him in repeated battles.

Capture & Death

Jugurtha became desperate and appealed to his son-in-law, Bocchus, promising him a third of his kingdom in return for assistance in defeating Marius. Bocchus accepted the offer and the allied forces fell on the Roman army as it was on the march retiring to winter quarters. Marius ably held off the much larger force and then defeated them, inflicting heavy losses on Jugurtha's army. Bocchus withdrew from the field with his forces largely intact because he had refused to commit many troops once he had seen how fiercely the Romans fought.

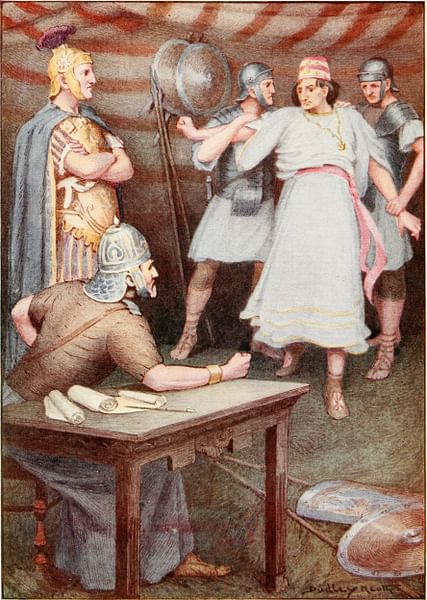

Bocchus then secretly contacted Marius asking for a conference and Marius sent his subordinate (and the future dictator of Rome) Lucius Cornelius Sulla (c. 80s BCE) to handle the details. Sulla told Bocchus that an accord could only be reached if he handed over Jugurtha. Jugurtha, at the same time, learned that Sulla was at the court of Bocchus and demanded his son-in-law deliver the Roman to him.

Bocchus invited Jugurtha to his palace with the understanding that he was coming to receive Sulla as a prisoner while also telling Sulla that Jugurtha would be taken as soon as he arrived. No one seems to have known which way Bocchus was actually leaning until the moment he had Jugurtha arrested and handed him over to Sulla in 105 BCE.

Jugurtha was brought to Rome in chains, featured in Marius' triumph and was then imprisoned in the dungeon known as the Tullianum. According to one account, he was left there to starve to death while, in another, he was executed by strangulation in 104 BCE. For his assistance in capturing Jugurtha, Bocchus was given the lands in Numidia his father-in-law had promised him for helping him defeat Rome.

Jugurtha proved to be one of the most dangerous of Rome's enemies as he was not only an adept military leader but understood how to exploit his enemy's great weakness: avarice. Having observed first-hand the Romans' easy attitude toward bribery, he made the most of it in the belief that everyone involved in the transaction would benefit. In his early efforts he proved himself right but eventually found that one can only buy one's self out of trouble for so long.