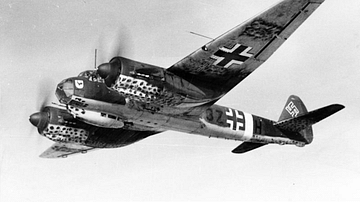

The Junkers Ju 87 'Stuka' was a two-seater dive-bomber plane used by the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) in various theatres of the Second World War (1939-45). The Stuka, with its distinctive angled wings, excelled when combined with armoured divisions in Germany's blitzkrieg ('lightning war') tactics in the early years of the war, but its inferior speed and manoeuvrability compared to single-seat fighters meant that it was ultimately restricted to hitting static targets where the Luftwaffe enjoyed air superiority.

Design & Development

In 1934, the German aircraft company Junkers was commissioned by the Nazi regime to design a prototype dive bomber. The idea was that a dive-bomber aircraft would be capable of delivering bombs at a lower altitude and with more accuracy than traditional high-altitude bombers, which dropped their loads vertically. Three prototypes were produced with design adjustments made to ensure the wings of the aircraft could withstand the force of diving from altitude. The best Junkers design, which included a Junkers Jump 210A engine, impressed against competition from rival manufacturers Arado, Hamburger, and Heinkel. Both Junkers and Heinkel were commissioned to produce 10 aircraft each. Several Ju 87s, as they were now classified, were tested in real combat conditions in the Spanish Civil War (1936-9) where they were flown by Germany's Condor Legion.

The Junkers Ju 87 had two seats, one for the pilot and one immediately behind for the rear gunner/radio operator. The aircraft gained the nickname 'Stuka', short for Stürzkampfflugzeug, meaning 'dive-bomber' in German, although the Germans themselves nicknamed the plane 'Berta'. The Stuka's bomb load mechanism "swung the weapon clear of the fuselage and propeller arc before it was released" (Saunders, 30). This feature, combined with the aircraft's ability to dive at a steep 80-degree angle (helped by a special dive-braking system), meant that it could strike a target with a much higher degree of accuracy compared to other types of bombers. Hitting a moving or small target remained a challenge and so, given that there was a mere 1.5-second window in which to release the bomb load at the bottom of a dive, only the most skilled Stuka pilots could regularly hit the objective of their extensive training: a 10-metre radius circle. Nevertheless, dive-bombing "proved four times more accurate than normal horizontal bombing from altitude" (Dear, 115).

By 1938, the main Stuka production plant was the Weser plant at Berlin-Tempelhof. Further design tweaks were made to the fuselage and distinctive fixed landing gears with their 'trouser' covers. The angled, 'gull' wings of the Stuka also set it apart from other aircraft of the period. Over the course of several new production models, a much more powerful engine was installed, the most powerful being capable of an impressive 410 km/h (255 mph), although this was significantly less than the best Allied or Axis single-seat fighters of the period, which could fly well over 480 km/h (300 mph). As the Nazi regime geared up for a war of conquest in Europe, Junkers was required to step up Stuka production to 60 models a month. By the start of WWII, which began with Germany's invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Luftwaffe had 336 Stukas, a figure which soon increased to 557. These aircraft were divided into nine Luftwaffe Stukagruppen. The aircraft was also flown by the Italian air force and by the air forces of other Axis allies such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, and Romania.

Specifications & Armaments

Stukas had a wingspan of just over 13.8 metres (45 ft) and a length of around 11.3 metres (37 ft). The Jumo 211J-1 12-cylinder inverted-Vee piston engine gave the Stuka a maximum power of 1,400 hp (1044-kW) and a top speed of 410 km/h (255 mph) at 3,840 metres (12,600 ft). The aircraft's maximum ceiling was 7,290 metres (23,915 ft) and its maximum range was 1,535 kilometres (954 mi) although 800 kilometres (500 mi) was more typical. A specialised anti-shipping model with extra fuel tanks could fly even further. The extra fuel tanks were placed in the outer wings and in a drop-tank below the fuselage, giving, in total, an extra 600 litres of fuel compared to a standard Stuka. The Junkers Ju 87 was produced throughout the war with later Stukas given better armour plating.

Stukas were armed with two 7.92-mm (0.31 in) MG 17 machine guns, one set in each wing, and, for the rear-facing cockpit gunner, flexible-mounted twin MG 81Z machine guns of the same calibre. Some later models were armed with a single anti-tank cannon or with one 37-mm cannon in each wing. The aircraft could carry a maximum bomb load of 1,800 kg (3,968 lbs) in the form of a single bomb or several combinations of lighter ones. A standard combination was to carry one or two 50-kg (110-lb) armour-piercing bombs under each wing and a single 250-kg (550-lb) bomb under the fuselage. Stukas could be fitted with skis if required and equipped with engine filters for desert warfare.

Operations

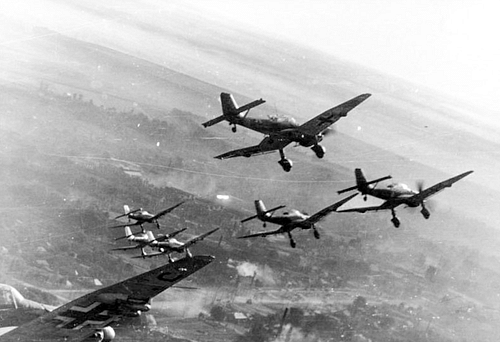

Stukas were an important component of Germany's blitzkrieg tactics employed against Poland, Norway, the Low Countries, and France in the first year of WWII. Stukas delivered bombs with precision, acting much like a form of heavy artillery and, used in tandem with fast-moving tanks whose advance they enabled, the dive bombers caused chaos with enemy defences, but especially artillery, anti-aircraft guns, lines of communication, and transport networks at and behind the front lines. The aircraft made a distinctive screaming whine when diving thanks to a deliberate design addition that funnelled air through small apertures, adding to the terror factor of being attacked by bombs from a low height. As Charles de Gaulle, a colonel in command of the French 4th Armoured Division in 1940, noted, "All the afternoon the Stukas, swooping out of the sky and returning ceaselessly, attacked our tanks and lorries. We had nothing with which to reply" (Gilbert, 124).

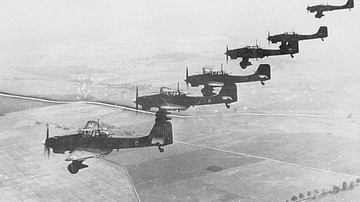

The typical offensive tactic was for a single line of Stukas to attack a smaller target head-on or for a trio to attack larger ones in a horizontal formation. The Stuka pilot had to carefully take into account the direction of the wind, but once in its high-speed dive, which often reached 450 km/h (280 mph), the aircraft proved almost immune to attack by a chasing fighter, as noted by Flight Lieutenant Frank Carey: "In the dive they were very difficult to hit because, in a fighter, one's speed built up so rapidly that one went screaming past it. But it couldn't dive forever!" (Saunders, 49).

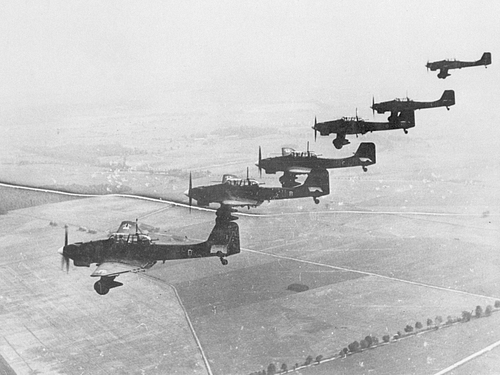

The Stukas flew to their targets in large formations, sometimes 100-strong. Heading to the target area, they adopted a stepped formation to maximise the defensive capabilities of the rear gunners. The fighter escort, when provided, was usually split into two: one group defending the space above the Stukas yet to attack the enemy and the second group positioned much lower in the sky where the Stukas would come out of their dive.

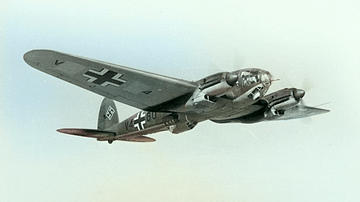

Stukas played a part in the Battle of Britain (Jul-Oct 1940) and were often used to attack static installations like radar towers and airfields as well as merchant shipping in the English Channel. However, the aircraft's vulnerability to faster and much more manoeuvrable fighters like the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire meant that, eventually, the Stuka was withdrawn from the battle or only used when it could be provided with its escort of fighters like the Messerschmitt Bf 109. As Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, ordered: "Until the enemy fighter force has been broken, Stuka units are only to be used when circumstances are particularly favourable" (Dildy, 66). The Royal Air Force was never broken. During the Battle of Britain, 67 Stukas were lost, 21.5% of the initial Stuka force (Dildy, 63). The Stuka's weight and fixed undercarriage proved to be insurmountable liabilities, and the aircraft was replaced by the Junkers Ju 88 medium bomber as the Luftwaffe's dive bomber of choice.

Stukas were deployed by the Luftwaffe to assist the armoured divisions of General Erwin Rommel (1891-1944) in the Western Desert Campaigns in North Africa. Here, air superiority for either side remained fragmentary, and so the weaknesses of the Stuka compared to fighter planes were less important. Stukas attacked supply routes, supply dumps, and fixed defences such as at the Battle of Bir Hakeim in May-June 1942. A Free French force was defending this outpost of the Allied Gazala Line defences that protected access to the vital port of Tobruk. Susan Travers, the sole female member of the French Foreign Legion defending Bir Hakeim, described the multiple Stuka attacks as like "a plague of silver locusts hovering above us" (Holland, 105). Stukas helped Rommel take Bir Hakeim and win the wider Battle of Gazala, a victory which ultimately led to the capture of Tobruk by the Axis powers.

Stukas were deployed in the Mediterranean and on the Russian front during the war. In the former arena, Stukas could be used to drop a single torpedo while on the Eastern Front, a specially adapted Stuka model was even used to pull gliders. By 1943, developments in Soviet fighters meant that Stukas became just as vulnerable as they had been on the Western Front.

In total, around 5,700 Stukas were built during WWII. Never quite recapturing the fearsome reputation it had earned in the first year of the war, the Stuka, nevertheless, proved itself an accurate means to deliver bombs, and this, at times, more than counterbalanced its obvious defects of poor speed and manoeuvrability.