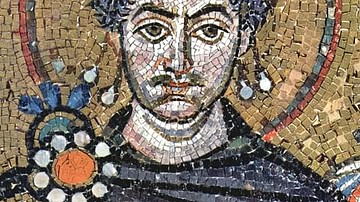

Justinian II “the Slit-nosed” ruled as emperor of the Byzantine Empire in two spells: from 685 to 695 CE and then again from 705 to 711 CE. It was after his first reign and prior to his exile that his nose was cut off by the usurper Leontios and so Justinian acquired his nickname. Unpopular with his people, whom he incessantly overtaxed, and suffering from a justified reputation for cruelty and disproportionate vengeance on those whom he perceived had wronged him, Justinian also struggled on the battlefield. He might have been one of the very few emperors to regain his throne but the fact that he was kicked off it twice by rebellious usurpers with no imperial connections is significant. Seemingly attacking cities at random, butchering anyone remotely regarded as a threat, and even laughing when he lost his own fleet in a storm, Justinian had descended into madness, and his second reign is now remembered as one of the most brutal and terrifying in Byzantine history.

Succession

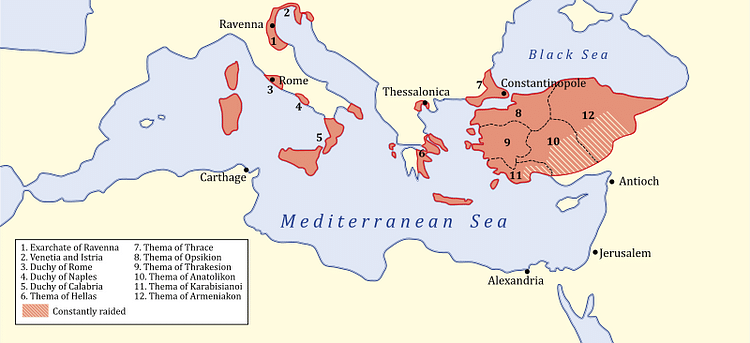

Justinian was born in 668 CE, into the Herakleios dynasty, the son of Constantine IV (r. 668-685 CE) and Anastasia. When Constantine died of dysentery in 685 CE, his son and chosen heir, now Justinian II, inherited a troubled empire. The one positive was that Constantine had somehow seen off the siege of Constantinople by the Umayyad Caliphate between 674 and 678 CE. The Arabs, under the leadership of Caliph Muawiya (r. 661-680 CE), had made significant gains in Asia Minor and the Aegean, but when their fleet was torched by Greek Fire in 678 CE, the caliph was forced to sign a 30-year truce with Byzantium. It was the first major defeat the Arabs had suffered since the rise of Islam. In 679 CE Muawiya was obliged to give up the Aegean islands he had conquered and pay a hefty annual tribute.

Elsewhere, though, the Byzantines had been less successful, and the Arabs in North Africa and the Bulgars and Slavs in the Balkans had been making inroads into the empire. Treaties with the Avars and Lombards, as well as some gains in Cilicia, and the establishment of a protectorate over most of Armenia at least meant the Byzantines were shoring up the holes and slowly turning around the steady decline that had beset them for half a century. There was still much work to do, though.

The young emperor seemed determined to live up to his famous namesake Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE), one of Byzantium's greatest rulers, but, as the historian J. J. Norwich here describes, he was not quite of the same calibre:

Intelligent and energetic, he showed all the makings of a capable ruler. Unfortunately, he had inherited that streak of insanity that had clouded the last years of Heraclius and was again apparent in the ageing Constans. Constantine IV had died before it could become manifest; in his son Justinian, however, it rapidly gained hold, transforming him into a monster whose only attributes were a pathological suspicion of all around him and an insatiable lust for blood. (102)

The new emperor was only 16 when he took his place on the Byzantine throne, but, nevertheless, he enjoyed some early military successes in Armenia, Georgia, the Balkans, and Syria. Then, as the Arab armies ignored the agreed truce and pressed further into Byzantine territory in Asia Minor, Justinian was obliged to withdraw his own armies from elsewhere to meet this new threat. Consequently, the gains in the north were gradually lost. Both his spells as emperor would be ones of military weakness, but for the moment, there were more pressing matters to deal with within the empire itself.

Domestic Policies

Justinian was a great one for consolidating his territorial gains and cementing into the Byzantine Empire the diverse peoples who made up his subjects by forcibly relocating vast numbers of them. The Mardaites (an independent Christian group in Asia Minor), in particular, were shoved about all over the empire. Cypriots were removed to Kyzikos, the important port on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. Slavs were another target, they were relocated in large numbers from the Balkans to the province (theme) of Opsikion in northwest Asia Minor. Finally, it is likely that Justinian was the creator of the new theme of Hellas (in the Peloponnese and parts of central Greece) and the kleisoura (military district) of Strymon, east of Thessaloniki.

Despite all this upheaval, or perhaps even because of it, the countryside in many areas of the empire was actually prospering. The class of independent peasants was booming, their living standards were rising and the empire could rely on a solid base for its army's recruitment needs. Justinian then went and rather spoilt it all by raising taxes to an unbearable level. In 691 CE this led to 20,000 Slav soldiers defecting to the Arabs, and Armenia was lost as a result. As revenge for this disloyalty, the emperor picked out a specific target: Slav families in Bithynia. Thousands of men, women, and children were either butchered or thrown into the sea.

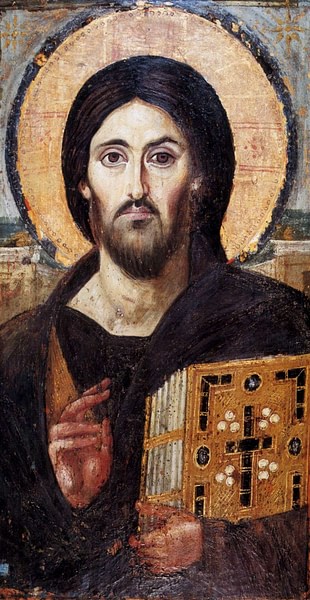

As was the case with many of his predecessors, the emperor took a keen interest in Church matters; Justinian was a staunch defender of orthodoxy. One group, in particular, was persecuted, the Paulicians, an Armenian sect which was keen on destroying icons. Monotheletism, that is the belief that Jesus Christ had or has only one will, was also condemned. Justinian convened the Council in Trullo (aka the Quinisextum Council), which met in Constantinople between 691 and 692 CE. The Council issued 102 canons on Church discipline, and when Pope Sergius I refused to accept them, Justinian tried to have him arrested.

The rumpus between the western and eastern churches was, no doubt, once again due to who exactly should have the right to decide the rules of Christianity as the Council's decrees were almost all trivial such as banning the curling of hair in a seductive manner or deciding the number of years of penitence for those who consulted fortune-tellers. There was one ruling which must have hit ordinary folk, and that was a ban on dancing to honour pagan gods and which, therefore, put a stop to masked-theatre, that art form having had a long association with Dionysos. It seems it was not going to be very much fun living under Justinian.

Justinian's piety is further illustrated in his gold coins, the first Byzantine coinage to depict Christ as the main image. The bearded and long-haired representation became the standard one for coins of the empire thereafter. The legends of Justinian's coins read: “Jesus Christ, King of those who rule” on the obverse and “Lord Justinian, the servant of Christ” on the reverse, which showed the emperor holding a cross. During his second reign, Justinian's coins depicted Christ more unusually as beardless and with short curly hair.

Exile

Then, in 695 CE, disaster struck Justinian's reign when the usurper Leontios (r. 695-698 CE), an ambitious general and commander of the Hellas province, seized the throne for himself. The general, the most senior in the army at the time, was backed by a wave of popular discontent from the peasantry at Justinian's continual heavy taxes and the outrage of the aristocracy at the constant extortion perpetrated by the emperor's entourage, led by the fearsome whip-carrying eunuch, Stephen of Persia.

Leontios, who had already been imprisoned for his ambitions between 692 and 695 CE, got his revenge by first parading Justinian in chains around the Hippodrome of Constantinople and then infamously slitting the nose of the emperor, a punishment which was designed to prevent him from holding future office as the convention was that an emperor had to be free of physical imperfections. Justinian, henceforth known as “the Slit-nosed” (rhinotmetos), was then exiled to Cherson in the Crimea. Others who had been closest to the throne were less fortunate - dragged through the streets of the capital behind wagons, they were then burned alive in the Forum Bovis.

Leontios' unsuccessful reign only lasted three years, and its chief low points were a devastating outbreak of plague and the loss of Carthage to the Arabs in 697 CE. In 698 CE he was himself removed by another usurper, Apsimar, a military commander in the Kibyrrhaiotai theme in southern Asia Minor. Ironically, Apsimar had been sent by Leontios to retake Carthage but, failing to do so, he returned and used his fleet to oust the emperor instead. In the usual “what goes around, comes around” of the Byzantine court, Leontios had his nose cut off and was exiled. Tiberios III, as Apsimar was now calling himself, did not achieve much more than his predecessor, though, and he oversaw both a failed invasion of Syria and the loss of western North Africa to the Arabs.

Second Reign

With the empire in trouble, Justinian was able to make his move to return to power. Crucially, the ex-emperor had the help of both his future son-in-law Tervel, the Khan of Bulgaria (r. 701-718 CE), to whom the emperor had promised his daughter in marriage, and the Khazars, the semi-nomadic Turkish tribe on the other side of the Black Sea. The Khazar leader Ibuzir became Justinian's brother-in-law as the would-be two-time emperor promptly married his sister Theodora. In 705 CE Justinian and his extended family besieged Constantinople. Tiberios had prudently repaired the ageing sea walls of the city, but only three days after setting up camp outside the Theodosian Walls, the attackers gained entrance by an aqueduct pipe. Caught by the total surprise, the palace guards surrendered, and Tiberios fled to Bithynia. Justinian, now wearing a gold false nose, was back on the throne in the golden reception room he had himself added to the Great Palace. He then crowned his foreign-born wife Empress Theodora, an unprecedented move.

The emperor's second spell of rule (705-711 CE) revealed him as a nasty tyrant, and his first act was revenge. Tiberios was pursued and captured while Leontios was brought back from exile. Both were paraded in chains in the Hippodrome, pelted with excrement, and then executed. Next, Justinian went for the army and those generals who had sided with Tiberios. The biggest name was the ex-emperor's brother, Heraclius, but many others were hanged in a public display along the city's Theodosian Walls. The bishop of Constantinople who had crowned both of the two usurpers was blinded and exiled. Still others who were deemed of dubious loyalty were sown into sacks and lobbed into the sea.

On the military front, Justinian proved as ineffective as ever in stopping the Arabs overrunning much of Asia Minor from 709 to 711 CE. The situation was not at all helped, of course, by the emperor's murder of just about any capable officer in the Byzantine army. Tyana in Cappadocia was lost to the Arabs in 709 CE. A Byzantine attack on Ravenna - of mysterious motivation - was carried out with success in the same year, Justinian having had all the nobles of the city rounded up, shipped to Constantinople and then executed. Despite this attack so close to home, the new Pope, Constantine, travelled to Constantinople in 711 CE, and a reconciliation was made after the upset over the Council in Trullo. It would be the last time a Pope visited Constantinople until Paul VI in 1967 CE.

The cordial interlude of friendship was interrupted by Justinian making more enemies for himself and attacking Cherson - perhaps in vengeance for having been exiled there, but now just about all of the emperor's actions seemed like madness. The city was sacked, seven key nobles were roasted alive while others had weights tied around their legs and were thrown into the sea. On the way home, though, Justinian's entire fleet was sunk in a storm. The emperor was said to have laughed when he heard the news.

Then a serious rebellion broke out led by the general Philippikos in 711 CE. Once again, Tervel stepped in and provided the emperor with an army of 3,000 men. Tervel had already been granted the title of Caesar and given a favourable trade deal, but his force was not enough to turn the tide of change, and Justinian was ousted for the second time.

Death & Successors

Philippikos, backed by the Khazars who had just retaken Cherson, supported by the Byzantine army, and bolstered by the news that other parts of the Crimea had already rejected Justinian's right to rule, seized power in 711 CE. To ensure there would be no third time lucky for Justinian, the emperor was executed on 4 November 711 CE. Shortly after, his son and co-emperor Tiberius was murdered too, along with most of his father's advisors. Philippikos would, though, reign for less than two years as the Byzantines witnessed an ever-changing roundabout of emperors and ever-more calamitous military defeats abroad. The trend would continue, too, until Leo III took the throne and provided some much-needed stability between 717 and 741 CE.