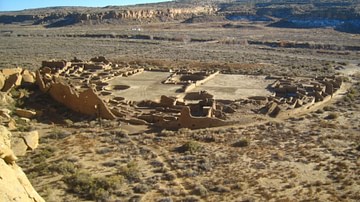

The Kachina (also “Katsina”) cult refers to the specific religious practices centered on the kachina, which is a spiritual entity and divine messenger of the Puebloan peoples as well as the Hopi, Zuni, Tewa, and Keresan tribes in what is the present-day Southwestern United States. The Kachina cult emerged under mysterious circumstances in the desert Southwest after a period of profound social, cultural, and religious turmoil in either the late 14th or early 15th centuries CE, following the abandonment of centers like Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Wupatki, and Canyon de Chelly. The exact origins of the Kachina cult remain the subject of fierce, scholarly debates. Despite the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores and Christian missionaries in the region during the 16th century CE, the Hopi and the Zuñi peoples were able to maintain their temporal and religious freedoms, ensuring that the Kachina cult has survived and flourished well into modern times.

Historical Emergence & Importance

The genesis of the Kachina cult is shrouded in mystery and is still contested by academics. Various theories tie the Kachina cult and Kachina dolls to ancient religious practices and rituals in Mesoamerica, while other ethnologists and anthropologists believe that the Kachina cult arose organically in the desert Southwest as a reaction against older ancestral Puebloan traditions and religious beliefs in an epoch marked by extreme drought and subsequent population displacement. Some have even theorized that the Kachina cult arose as an indigenous imitation of Spanish Catholicism.

It seems probable, however, that Mesoamerican beliefs and ritual practices came to the Southwest via Casas Grandes through trade and influenced the subsequent development of what ultimately became the Kachina cult. What is known from archaeological research is that pottery designs dating to the 1300s and 1400s CE from the Hopi settlement of Homolovi, located in what is now Arizona, show definitive kachina-like imagery. Perishable materials found in caves in southern Arizona and New Mexico's Rio Grande Valley point to early evidence for the Kachina cult, and archaeologists have also discovered murals of supernatural figures on several kiva walls and blocks with images similar to Kachinas as well.

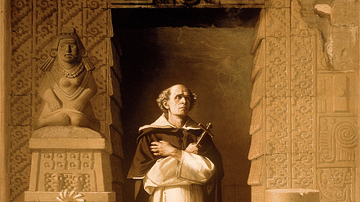

Spanish settlers and missionaries who arrived in what is now New Mexico in the mid-1550s CE testified to seeing grotesque images and figurines of the devil hung in the pueblos of the Native American tribes that they encountered. They also record witnessing satanic dances and other disturbing paraphernalia utilized in Native American ritual dances. Historians and anthropologists contend that these "satanic images and figures" were in actuality Kachina dolls, and the "satanic dances" were most surely Kachina dances in which individuals wore masks. (Native Americans believed that when male dancers wore Kachina masks, they were invested by the specific kachina spirit that they were trying to evoke.)

Colonial Spanish disdain for Kachina dances, dolls, and spirituality was so virulent that missionaries attempted systematically to destroy the religion of the Puebloan peoples by banning Kachina dolls, traditional dances, and ceremonies in the kivas in the 1650s and 1660s CE. Spanish missionaries accused those evoking the Kachinas of witchcraft and idolatry, and practitioners of indigenous religions were punished severely. This harsh approach ultimately backfired, culminating in the revolt of the Puebloan peoples - along with their Zuñi and Hopi neighbors - against the Spanish in 1680 CE. The "Pueblo Revolt" or "Popé's Rebellion," was a success, and Puebloan rebels drove the Spanish out of New Mexico for 12 years. Although short-lived, the Pueblo Revolt brought the Puebloan peoples, the Hopi, and the Zuñi a degree of freedom and some autonomy from future Spanish efforts to eliminate their religion and cultural traditions in the aftermath of the Spanish reconquest of New Mexico in 1692 CE.

Role of the Kachina & Kachina Season

The Kachinas (also "Katsinam" in the plural) function as spiritual guides or intermediaries between people and their gods within Puebloan religion. Kachina means "life-bringer," and various kachina rituals and ceremonies are believed to be essential in securing the growth of crops, the summer rains, and good health in an extreme climate. To survive in such harsh terrain, the Puebloan peoples and their neighbors developed elaborate rituals designed to garner spiritual assistance in achieving life's necessities. The Kachinas, in turn, can be viewed as those divine entities that regulate the phases of their terrestrial existence. Kachinas are thus not gods, per se, but rather animistic and ancestral spirits. The Hopi, Zuñi and other Puebloan peoples venerate nearly a thousand different kinds of Kachinas, which represent everything from wild animals and foods, to insects, plants, and even death itself. The concept of the Kachina is delineated in three different ways:

- as a spiritual entity

- through dances in which individuals represent various Kachina at rituals and ceremonies

- through carved Kachina dolls.

At the age of ten, every member of the Hopi tribe is initiated as a member of the Kachina cult. The fundamental belief, expressed by the individual being initiated is that everything in the temporal world has two distinct elements: A visible object as well as a complimentary spiritual variable. This duality, as it were, is said to be a blend of masses and energies. The Hopi faithful believe that the physical manifestations of the Kachinas are observed in the form of steam or mists that could appear on the ground, in the mountains, or in the skies.

The so-called "Kachina season" starts in December and lasts through July. These ceremonies take place according to the lunar calendar. In Hopi villages, kivas - ceremonial chambers built underground - are opened to the Kachinas so that they can begin to renew the world and prepare the population for springtime. When the kivas are closed in the summer, it is believed that the pathway used by the Kachinas is also closed until a new season begins. Boys are initiated into the Kachina cult in February just before the growing season begins. Various dances - some lasting all day - mark the entirety of the Kachina season, but the final Kachina ceremonies commence around or just after midsummer's day. The Kachina are thereafter sent to the sky, mountains, and back into the kivas.

Kachina Dolls

Kachina dolls first received widespread attention by Western visitors to the desert Southwest in the late 1800s and early 1900s CE, but as previously noted, they have existed for hundreds of years. Each tribe of Pueblo has their own specific form, number, and style when it comes to Kachina dolls. Hopi and Zuñi Kachina dolls are the most prized and lauded for their artistry today. Curiously, the Zuñi produce very few Kachina dolls compared to their Hopi neighbors, and their Kachinas are thinner and taller than those of the Hopi. The Zuñi also add more decoration to their Kachinas with regard to clothing than the Hopi. Traditionally, the Hopi carved their Kachina dolls from a thoroughly dried cottonwood tree. Juniper was sometimes used too, but this was quite rare. Natural mineral paints in red, pink, yellow, and green give Kachina dolls their unusual and intriguing pigmentation.