Kahina (7th century CE) was a Berber (Imazighen) warrior-queen and seer who led her people against the Arab Invasion of North Africa in the 7th century CE. She is also known as al-Kahina, Dihya al-Kahina, Dahlia, Daya, and Dahia-al-Kahina. Although she was finally defeated, her resistance later served as a model for other freedom fighters.

Her birth name was Dihya, or some variant thereof (“the beautiful gazelle” in the Tamazight language of the Imazighen) while “Kahina” is an Arabic title meaning “prophetess” or “seer” or “witch”. She is said to have had supernatural powers which enabled her to foretell the future. Although she is a champion of the native North African Imazighen people, she is best known by the title given her by her Arab enemies: al-Kahina.

She was the daughter (or niece) of the Berber king Aksel (died c. 688 CE, also known as Kusaila, Caecilius, Kusiela) who was a famous freedom fighter of the Imazighen people (also known as the Amazigh, “the Free People”, the indigenous name of the Berbers). Little is known of her life outside of her conflict with the Muslim Arab leader Hasan ibn al Nu'man (died c. 710 CE) whose Umayyad armies campaigned across North Africa.

Kahina defeated Hasan more than once and drove him from the region. Legend then claims that she engaged in a scorched earth policy to deprive the invading Muslims of any profitable goods and that this course led to a loss of support from her people. It may be, however, that the Arab armies themselves used the scorched earth tactic and later Arab writers attributed the destruction of the land to Kahina.

In her last engagement with Hasan, a significant number of her former allies fought against her. Commanding a greatly diminished force against overwhelming numbers, Kahina was defeated. She either died in battle, took poison to avoid capture, or was taken and later executed. Dates given for her death vary between 698, 702, and 705 CE, although the historical evidence suggests that the date of 698 CE is too early and her final battle was in either 702 or 705 CE.

Early Life & Legend

Kahina's life is only known through later Arab historians writing on the Muslim conquest of Africa. These historians, as well as other legends, claim that she was a Jewish sorceress who descended from the Beta Israel community of Ethiopian Jews. She is said to have been a royal member of the Jarawa tribe within the larger confederacy known as the Zenata Tribe of Mauretania; a princess, who then became queen and ruled over an autonomous state in the area of the Aures Mountains in modern-day northeastern Algeria.

Some sources claim that Kahina was a Christian, however, and that she derived her power from a Christian icon. At the same time, it has been argued that she practiced the indigenous religion of Numidia which included worship of the sun, moon, and veneration of one's ancestors. The claim regarding her power of prophecy is in keeping with this ancient belief in which the gods, or the spirits of the dead, could communicate with certain members of the tribe who had the gift of prophecy.

Legends suggest she could communicate with birds who were able to warn her of advancing armies. This story may have originated to explain her alleged prophetic gifts. Legends also claim she once married a tyrant who was persecuting her people and then murdered him on their wedding night.

Although she is commonly referred to as a “Berber Queen”, the indigenous people of the region know her as an Imazighen, which is the more accurate term. Scholar Ethan Malveaux comments:

The word Berber was a derivative of the Greek word Kapes Bap Bapo`owoi, which meant savage (later the English would compact it into Barbary); the Arab adopted the name for these African tribes who were once subjected by the Ancient Romans and who had (before the Muslim Conquest) wrested semi-autonomy from the Byzantine Empire. (171-172)

One of these semi-autonomous states was the kingdom of the Zenata tribe which may have once been part of larger coalitions of Imazighens in the region.

Kahina is usually described as tall and “great of hair”, which is usually interpreted to mean she wore her hair long and bunched in dreadlocks. She is usually depicted in the attire of the royalty of ancient Numidia: a loose-fitting tunic or robe worn with sandals and sometimes belted.

Numidia & Rome

Numidia as a unified kingdom flourished between 202-40 BCE, though the history and culture of the region are much older. It is considered the first Imazighen state established in North Africa and was founded by the king Masinissa (r. c. 202-148 BCE) following the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) between Rome and Carthage.

The two main tribes in the region were known as the Masaesyli, to the west, and the Massylii to the east. Although these people are commonly referred to as “tribes”, they may have been a coalition of different tribes under the leadership of respective chiefs. Masinissa united these tribes as the Kingdom of Numidia which was later divided between Mauretania and Rome following the so-called Jugurthine War (112-105 BCE) initiated by Masinissa's grandson Jugurtha (r. 118-105 BCE) against Rome.

As a province of Rome, the Imazighen became involved in the Roman Civil War between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great in 46 BCE, and the region was subsequently controlled by Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE-14 CE) after 31 BCE. Numidia continued as a Roman province after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE. It became the Praetorian Prefecture of Africa, under the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, following the defeat of the Vandals in North Africa in c. 534 CE and was then known as the Exarchate of Africa, remaining under Byzantine control.

The Numidians under Rome became a diverse culture of religious traditions. Judaism, Christianity, and the indigenous religion of the ancient Imazighen seem to have coexisted harmoniously or, at least, there is no evidence of religious turmoil in the region during this time. As part of “Rome's bread basket”, supplying the empire with grain and its army with mercenary cavalry, the region of the Maghreb (the Berber world) prospered.

The Arab Invasion

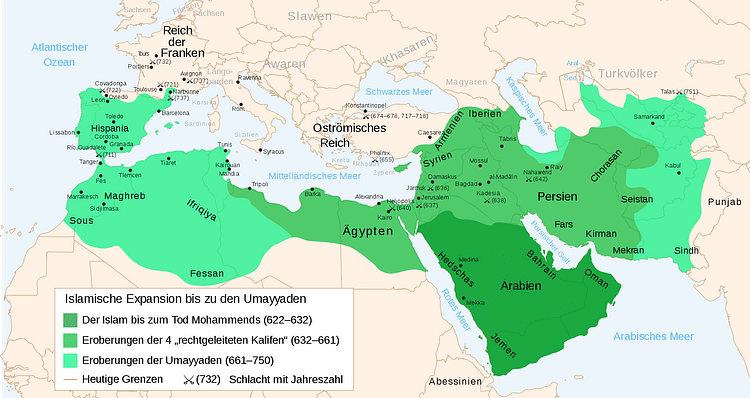

In the 7th century CE, the Arabian armies began campaigns of conquest following the establishment of the new religion of Islam. While scholars today continually debate whether these campaigns could be called jihads (“holy wars”), intended to convert large populations by force, there is no doubt that was the end result.

The contention that the Arabs were not interested in forced conversion comes from certain verses of the Quran which discourage it (2:62; 2:256; 4:93; 16:125, among others) but there are other passages which support and encourage the practice (4:76; 9:5; 9:29; 9:38-39, to cite only a few). It has also been claimed that the Muslim Arabs had no motive for forced conversion because non-believers were forced to pay a tax (the jizya) to live among Muslims and this was more profitable than forced conversion. At the same time, however, control over the resources and population of a region could prove far more profitable than a tax on unbelievers.

Arab forces had already conquered Mesopotamia and Egypt by 647 CE, converting the populace to Islam, when they moved toward the Maghreb. The Byzantine Empire was still in control of Carthage and the Maghreb at this time and the Byzantine Governor Count Gregory the Patrician mounted a defense against the invasion. Gregory was killed at the Battle of Sufetula in 647 CE, south of Carthage, and his successor paid the Arab forces a sizeable tribute to return to Egypt.

In-fighting among Arab factions prevented any further campaigns until c. 665 CE. The city of Kairouan (in modern-day Tunisia) was established as a base of Arab military operations in c. 670 CE and from there the general Uqba ibn Nafi (died 683 CE) launched his campaigns toward Mauretania in the west. The site was chosen for its relative safety from attacks by the Imazighen who had already mobilized to resist the Arabs through guerilla tactics. The resistance would soon shift their strategy to open war, however, under the leadership of Aksel of Mauretania.

Aksel's Resistance

Aksel mounted a defense and held his kingdom against the invaders but then went on the offensive, driving them back from his borders. Aksel had been a Christian who converted to Islam voluntarily sometime earlier because it seemed more profitable. As the Arab Invasion spread and threatened his autonomy, however, he abandoned the faith and returned to the indigenous religion of the Imazighen.

Using the native religion as a rallying point, he was able to attract more recruits to his army. He was captured by the Arab forces but was allowed to live, perhaps because of his knowledge of their religion or perhaps he pretended to still be Muslim. His life was spared but he was ordered to disband his troops and convert them to Islam. Aksel agreed, was released (or escaped), and then threw his army at the Arabs, defeating Uqba ibn Nafi's forces and killing him in 683 CE.

Aksel capitalized on his victory by expanding his territory and gaining more recruits but was killed in battle with the Muslim Arab leader Hasan ibn al Nu'man in either 686 CE or 688 CE. At this time, he may have been succeeded by his wife (or another female relative) named Koceila who reigned as queen. If Koceila did succeed Aksel, it was not for long as Kahina was in command of the army by c. 690 CE.

Reign of al-Kahina

Kahina is thought to have fought alongside Aksel in the 680's CE and proven herself in battle. This claim is supported through the acceptance by her troops as a competent military commander. She won an early victory against Hasan (date unknown) and forced his retreat. Hasan remobilized his troops and furiously took the city of Carthage in 698 CE. Now holding the northeast regions, he again attacked Kahina and was so badly defeated that he retreated either to Libya or Egypt.

Kahina's alleged gift of prophecy is said to have enabled her to foreknow how her opponent would form troops, how they would be reinforced, and what direction they would come from. Her perceived spiritual power has led to comparisons with the French heroine Joan of Arc (1412-1431 CE) and she also shares similarities with the Native American Apache seer and female warrior Lozen (c. 1840-1889 CE) who was able to anticipate and defeat U.S. Cavalry troops through precognition. It is said that by using her powers, Kahina may have won a third victory against Hasan, or perhaps an army under another leader while Hasan was in Egypt or Libya.

According to legend, during this engagement she was outnumbered by the Arab forces and fell back in retreat. Recognizing the direction of the wind, however, she ordered her army to set fires which the wind then carried to the enemy. The Arab army was forced to retreat and the land was so badly burned that any future campaigns would have to cross an arid wasteland without resources.

At this point in her story, there are two possible narratives. According to the Arab historians and legends, her victory by fire gave Kahina the idea to initiate a scorched-earth policy on a large scale. She is claimed to have believed that the Arabs were only interested in the riches of the land and that, if she removed these, they would leave her people alone. She therefore commanded her army to tear down the fortifications, destroy the cities and towns, and melt down the gold and silver. She further ordered orchards cut down, fields burned, and even private gardens destroyed.

She allegedly engaged in this tactic to save her people but, to those who lived in the towns and cities and relied on the fields and orchards, Kahina's policy was disastrous. Their homes and businesses were destroyed and the only option given them was a nomadic wandering in a region which had been largely destroyed by war even before Kahina set it on fire. Resentment toward the queen replaced the earlier admiration and many of her people turned against her.

The other possible narrative is that the Arab historians are attributing to Kahina a tactic known to have been used by invading Arab armies elsewhere. In Egypt, Libya, and Mesopotamia the invading Muslim Arabs routinely used scorched-earth tactics to subdue the populace. It is likely, therefore, that they did the same in North Africa with later writers then blaming the widespread destruction on the queen who had led the resistance against them.

It is possible, then, that Hasan, or another commander, initiated the scorched-earth policy in North Africa to demoralize the people – just as they had elsewhere – and it worked to break the resistance. Those who had formerly supported Kahina openly may no longer have been able to afford to with their crops and homes destroyed. It is also possible that, by this time, the people simply saw a Muslim Arab victory as inevitable; Kahina herself may have felt this same way as evidenced by the later surrender of her sons to Hasan.

Final Battle & Death

Sources differ on whether the Arab general who defeated Kahina was Hasan or Musa bin Nusayr (died c. 716 CE). Musa replaced Hasan as governor in North Africa but it is unclear when. Further, Musa is traditionally credited with completing the conquest of North Africa which Hasan had begun and also with recruiting Imazighen warriors for his conquest of Iberia and this came after Kahina's death.

It seems it was Hasan, then, who after reforming his army following Kahina's victory returned to meet her a final time. He was now facing a very different opponent than the one who had driven him from North Africa, however. Many of Kahina's former allies had gone over to Hasan whether due to the scorched-earth tactics which demoralized them or bribery. One of Kahina's sons either defected or was captured and is said to have informed on his mother's battle plans.

In either 702 or 705 CE Kahina met Hasan in battle. Before the armies engaged, she is said to have sent her two other sons to the enemy camp to be raised by Hasan as Muslim warriors. The battle went against Kahina from the beginning as she was badly outnumbered but her army fought valiantly and won the admiration of the enemy.

Accounts vary concerning her death; she may have been captured and later executed or may have poisoned herself, but the most commonly accepted account is that she died in battle with her troops, still clutching her sword. Her head was then cut off and brought to Hasan as a trophy.

By all accounts, Hasan respected Kahina as an opponent and her sons, who converted to Islam, were well cared for and would later lead their own armies against others who resisted Arab aggression. Kahina's people, on the other hand, did not fare so well as 30,000 – 60,000 of them were sold into slavery by the conquerors and shipped out of their native land. Small pockets of resistance still held out - and many of the wives of Numidian chiefs are said to have killed themselves rather than be taken by the Arabs - but between c. 705-750 CE North Africa was fully conquered and the people converted to Islam.

Conclusion

Kahina herself would live on through the works of Arab historians, most notably the great Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406 CE), working from earlier sources. Her reputation as a “Jewish Sorceress” comes primarily from Ibn Khaldun. She remained an obscure figure until she was seized upon by the French in the 19th century to support their military initiative in Algeria: a freedom fighter battling Arab aggression. At that same time, the Imazighen reasserted their claim to her as their heroine while Arab Nationalists in the region somehow managed to argue she was theirs.

Professor Cynthia Becker of Boston University comments:

Since the ninth century, accounts of [Kahina] have been adopted, transformed, and rewritten by various social and political groups in order to advance such diverse causes as Arab nationalism, Berber ethnic rights, Zionism, and feminism. Throughout history, Arabs, Berbers, Muslims, Jews, and French colonial writers, from the medieval historian Ibn Khaldūn to the modern Algerian writer Kateb Yacine, rewrote the legend of the Kahina, and, in the process, voiced their own vision of North Africa's history. (1)

In 2001 a statue of Kahina was raised in the Parc de Bercy, Paris as one of a number in an exhibit called “Children of the World” (Les Enfants du Monde). The exhibit celebrates world diversity and the unity of the human experience and the statue was designed by artist Rachid Khimoune to represent Algeria. In Algeria itself, a statue was erected in 2003, possibly in response to the Parisian work, in the town of Baghai, Khenchela Province, honoring Kahina. As her name becomes more widely known, Dihya al-Kahina of the Imazighen inspires not only her own people but those everywhere who honor her memory and sacrifice for the cause of freedom.